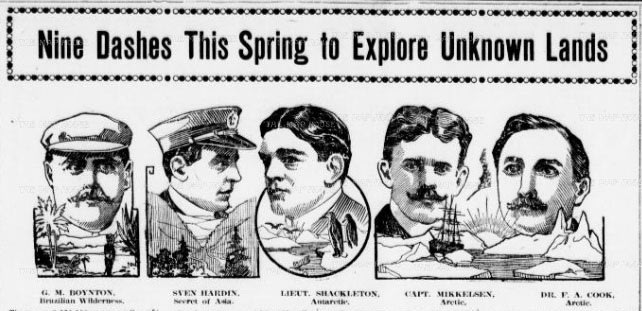

George Melville Boynton (far left) alongside Sven Hedin, Ernest Shackleton, Ejnar Mikkelsen, and Frederick Cook. Credit: Albuquerque Citizen, April 9th, 1908

George Melville Boynton was born in Laconia on the 15th of July, 1869. Little is known about his childhood, except that his father, Melville Cax Boynton, was a successful cloak merchant in New York City. George received a thorough education in Boston after which he lived (and likely worked) with his father in New York until the age of twenty. In 1889, a violent quarrel drove them apart after which they never spoke again. Afraid to return home and with only $10 in his pocket, George made the first of many brash decisions he would make over the course of his lifetime: he boarded a fruit ship heading for Rio de Janeiro in search of adventure.

By 1897 Boynton had returned to the United States and was living in San Francisco. This brief period of normalcy, however, was not to last. On the 18th of August he embarked on the most famous of his great adventures, walking around the world to win a $50,000 wager. According to contemporary news articles, Boynton made a bet with some wealthy friends in San Francisco (some sources claim that it was the mayor of San Francisco himself) that he could walk around the world without spending any money, relying entirely on the kindness of strangers. His proposed route was to take him from San Francisco to New York, then by ship to London, through all the major capitols of Europe, across Siberia to Vladivostok, through Japan, and back across the Pacific. He would finish by crossing the United States a second time before arriving triumphantly in Washington, D.C. He was required to complete the walk within a period of five years and was not allowed to spend any money along the way.

The French long-distance walker, Henri Gilbert, at Barcaldine, Queensland in 1900. Credit: State Library of Queensland.

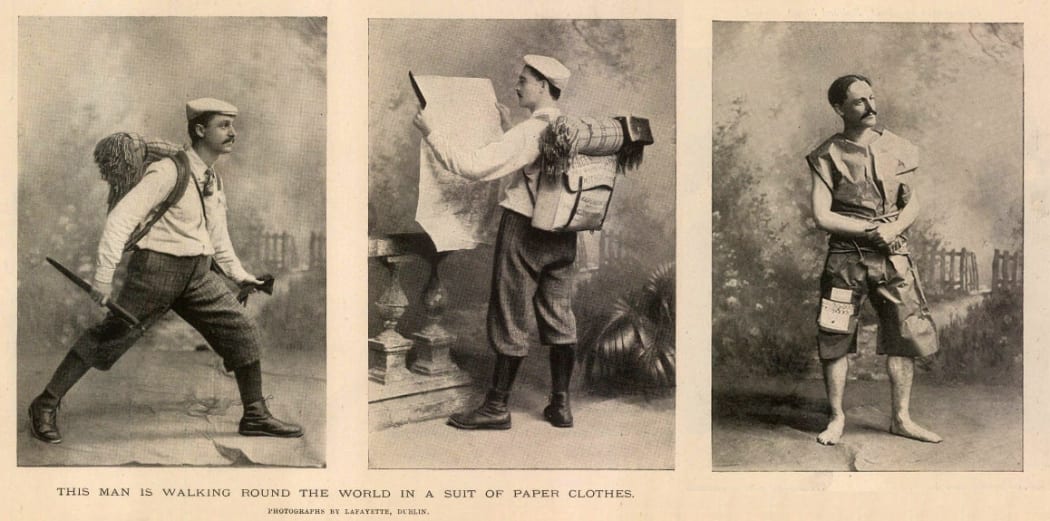

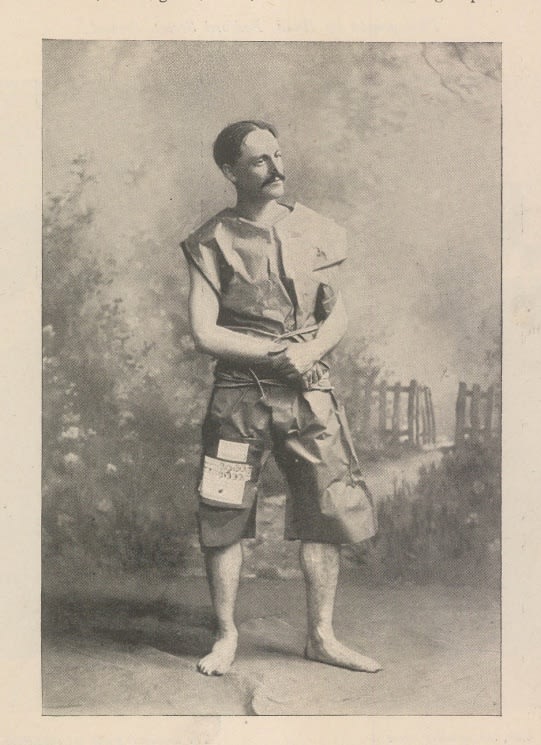

In a rather extreme interpretation of the wording of the bet, Boynton chose to begin his walk with absolutely nothing, including clothing. To avoid walking the streets of San Francisco in the nude, he hastily fashioned a suit of clothes out of brown paper, perhaps utilizing some of the skills he had learned working with his father, the cloak maker. Fortunately, before he had even left the city, a local San Francisco tailor took pity on the young man and gifted him a complete outfit of clothes, including a knapsack and some vital gear. Though he only spent a few hours in his ‘paper suit’, he brought it up often in newspaper interviews, and was more than happy to recreate the outfit during a visit to a London photography studio. The resulting photograph of George Melville Boynton striking a thoughtful pose in his paper suit was featured in prominent journals, including Sketch The Illustrated London News.

Boynton wearing a reconstruction of his famous paper

Boynton’s stay in London was short – only four days – and he was soon on the move again, passing through Birmingham on his way to Liverpool. From Liverpool he sailed to Ireland, arriving in Queenstown (Cobh) on the White Star Line’s Britannic on the 31st of March. For the next month he travelled extensively through Ireland, visiting Killarney, Limerick, Dublin, and Belfast as well as many smaller towns and villages. His daily travels were covered in minute detail by local newspapers, particularly those in Dublin and Belfast.

Upon entering the studio, Boynton was entranced by a photograph of a mysterious woman and demanded to know her identity. The proprietor explained that the woman was his niece, Sarah Harding Lauder, who lived with her family in Glasgow, her father being the manager of the Glasgow branch of the Lafayette firm. Without a moment’s hesitation, Boynton walked to Belfast, boarded a ship for Glasgow, introduced himself to Sarah’s father and asked for her hand in marriage. Sarah seems to have been equally taken with the mysterious stranger, as the couple were married less than a week later in Edinburgh on the 11th of June, 1898.

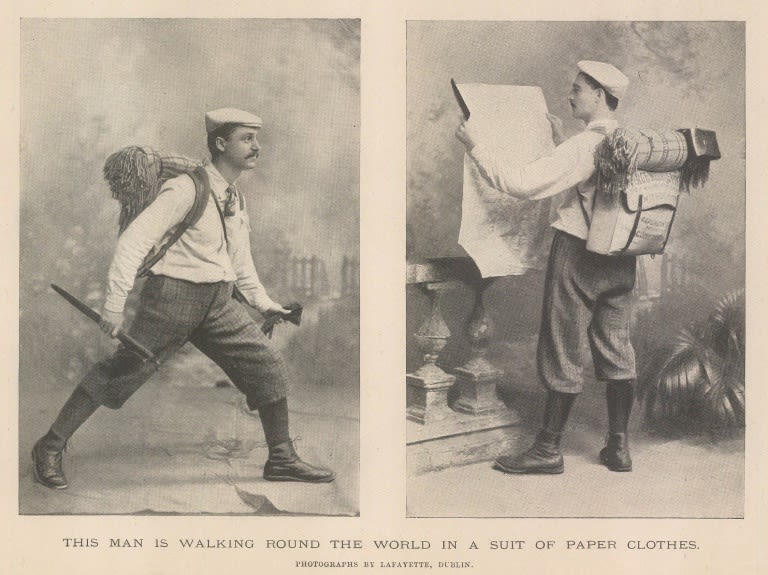

Boynton in his walking attire from The Sketch, June 15th, 1898. These are the photographs taken at the Lafayette studio in Dublin.

On the 30th of July, Boynton left London on a ship bound for Lisbon. On his arrival in Lisbon, he applied to the US Legation for a passport to allow him to cross the border into Spain, a bizarre choice as Spain and the United States had been at war since April. Curiously, George’s passport application was co-signed by his new brother-in-law, James Stanley Lauder, who had apparently travelled with him from London. Boynton intended to capture photographs of his walk across Europe, so perhaps James Lauder was sent to deliver the camera equipment and instruct Boynton on its use. Or perhaps the eighteen-year-old was simply enthralled by his mysterious new brother-in-law and went along for the adventure.

Boynton’s passport application to the US legation in Lisbon. Note the signature of James Stanley Lauder, his new brother-in-law.

George and Sarah were together for less than two weeks before Boynton again departed, this time for Ireland. Within eight months of the wedding he had already sent her a letter encouraging her to file for divorce. When she refused, Boynton filed for divorce himself, admitting during the trial that he had repeatedly been unfaithful and that he intended to return to the United States to pursue a mining interest in Colorado and had no intention of bringing Mrs. Boynton with him. He even joked in court that he was going to name his mining company after one of his mistresses, a cruel joke, but one that was reported with glee in the Scottish press. After three years, the unhappy marriage was finally dissolved on November 15th, 1901. It is reasonable to wonder whether the marriage was simply a matter of convenience for Boynton. Two weeks before the wedding the South Australian Register reported that he was searching for “some admiring firm to present him with a camera and a number of photographic plates.” Perhaps he saw in Sarah Lauder an opportunity.

Having failed to complete his walk around the world, Boynton was temporarily unoccupied, but he would not remain so for long. After his brief visit to his wife in Glasgow during the spring of 1899, George returned to Ireland for a second time, perhaps to revisit some of the contacts he had made during his first tour of the country. As he travelled he gave lectures in town halls about his experience walking through Spain, usually to raise money for local charities. His lecture on the 22nd of March, 1899 at the Ulster Hall in Belfast was advertised as featuring “the most beautiful Limelight Views ever seen in Belfast”, an indication that Boynton must have taken some photographs during his Iberian walk. It was during this time that he realized that he could raise money just by walking and lecturing. With this new scheme in mind, Boynton returned to New York to begin raising money for an expedition which, if it had succeeded, would have placed him amongst the greatest explorers of the age. He intended to fly to the North Pole.

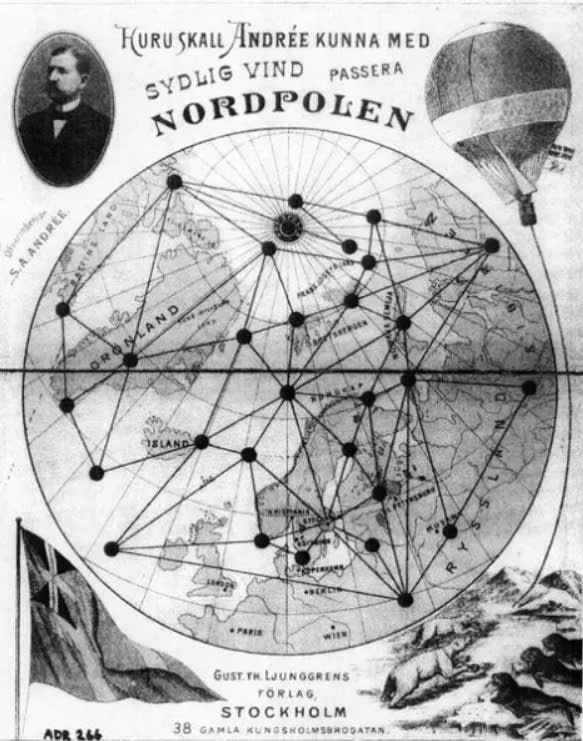

A Swedish board game from 1896 showing S.A. Andrée and his balloon, the Eagle. Credit: Wikimedia (public domain).

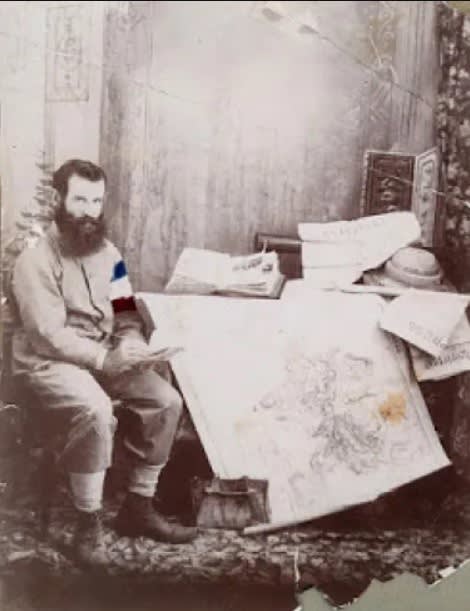

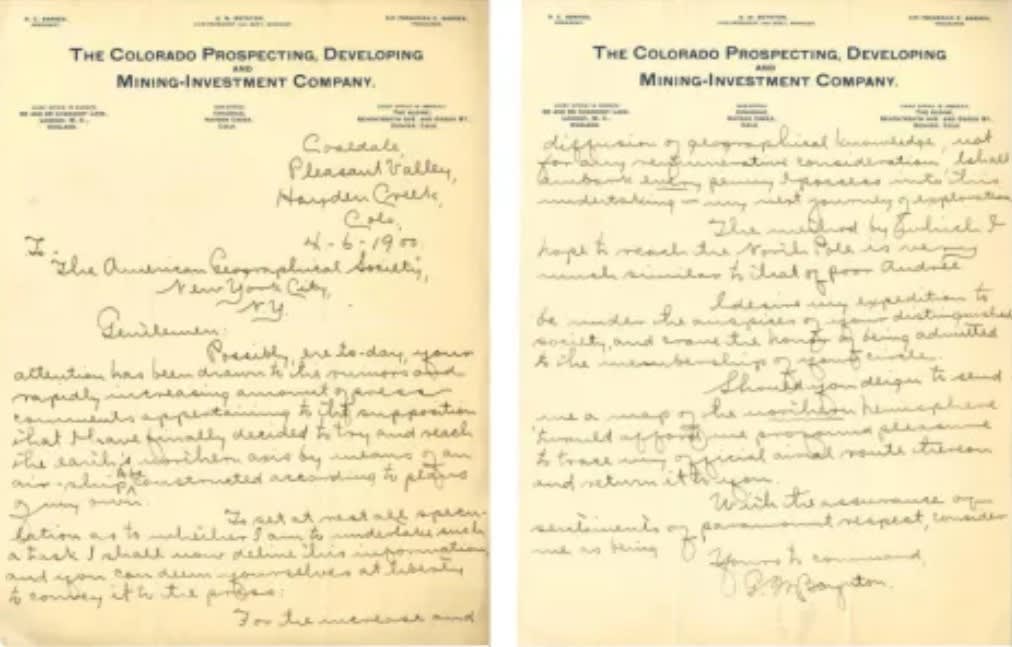

For Boynton to think that he could overcome the obstacles which had defeated Andrée was an act of monumental ignorance. He had none of the technical expertise, no prior experience with arctic conditions, and no survival skills beyond a creditable endurance for long-distance walking. Despite all of these flaws, he appears to have been quite serious in his proposal, going so far as to draw up technical specifications for his craft and sending a map of his proposed route to the American Geographical Society. Andrée’s expedition was fortunate enough to receive funding from Oskar II, the king of Sweden, and from Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite and the creator of the Nobel prizes. Boynton was not so well-connected and needed to rely on a far more inventive fundraising method. Coincidentally, his recent experience walking through Ireland had taught him that people were more than willing to donate to a worthy cause if properly inspired, and so he started walking.

Boynton’s letter to the AGS explaining his North Pole expedition and requesting a map on which to draw his route. Credit: American Geographical Society archive.

Left: Noah Barnes as featured in the Salida Record. Right: One of the entrances to the Montezuma mine. Credit: The Salida Record, September 19, 1902.

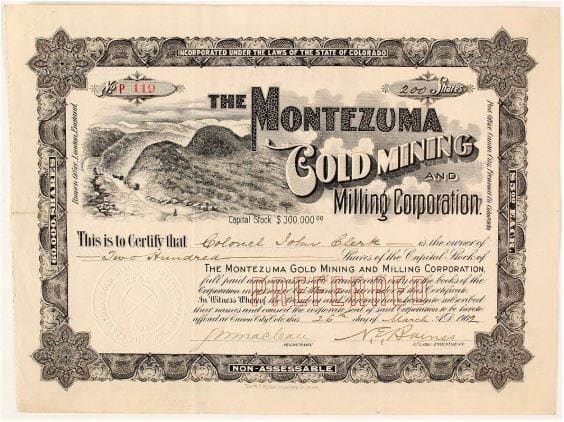

A year later in June, 1901 they formed the Montezuma Gold Mining and Milling Corporation. Shortly thereafter, Noah Barnes made the decision to move his entire family from London to Colorado. They founded the town of Barnes City on the banks of Hayden Creek, which by 1904 was a flourishing community of 300 well-built structures. The company had an initial capital stock of $300,000 divided into 60,000 shares at $5 each. The Montezuma claims were expected to produce over $1,000,000 worth of gold and silver in 1903 alone, so not surprisingly the shares sold extremely well. In an interview with the Salida Record newspaper in September, 1902, Barnes predicted that “three-quarters of a million dollars annually will go to England as dividends to shareholders”.

An original stock certificate from Boynton’s Montezuma Gold Mining and Milling Co.

The Montezuma Gold Mining Corporation’s elaborately designed stock certificates lent the company an air of legitimacy, which in hindsight it did not deserve. It was later discovered that several of the mines had been artificially sprinkled with high-grade ore from other mines to make them appear more productive, a process known as salting. Noah Barnes was accused of loading his shotgun with wads of high-grade ore and blasting each of the mining claims whenever the assayers were due to visit. In the end, no dividends were ever sent to the shareholders in London and the company declared bankruptcy. Noah Barnes spent several years in a Colorado prison for this fraud, and would later be incarcerated at Sing-Sing prison in New York for defrauding members of the German aristocracy, including Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia using similarly fraudulent mining claims.

We cannot say for certain to what degree Boynton was aware of the fraud, though he does not appear to have served any prison time. We know that he was back in Britain to testify at his divorce hearing in November, 1901, so it may be that Boynton had sold his stake in the company before any illegal activity began.

Tellingly, his name does not appear on the stock certificates alongside Barnes’ own name. Once again we are left wondering whether Boynton was naïve and innocent or whether he was a conniving swindler who manipulated Barnes and left him to take the fall.

Boynton the Businessman

Boynton’s activities over the next five years do provide some clarity on the question of his legitimacy. The Montezuma Mining Corporation was simply the first in a string of largely fraudulent business endeavours, many of which used partnerships with prominent members of society to mask the fraud. In January of 1902, after returning from London, Boynton established the San Jan Petroleum Corporation in Arizona. The company’s capitalization was $15,000,000, an enormous figure at the time. His partners included James H. Peabody, the governor of Colorado, and Murdoch Maclaine, 23rd Chief of Clan Maclaine of Lochbuie.

In September he founded The Mineral Exploration and Development Corporation of the American Continent in Phoenix, Arizona, and in the same year he dissolved the United States Mineral Syndicate a company he had founded just the year before. His partner in the former endeavour, Charles Allanson-Winn, fourth Baron Headley, was a member of the English peerage who had already declared bankruptcy once for unsound investments. He was the ideal target for a con-artist like Boynton. Finally, in 1907, he established the American Copper and Silver Company with the intention of scouting Central and South America for valuable mining opportunities. In the end, all of these businesses failed without producing any dividends to their shareholders.

Charles Allanson-Winn, fourth Baron Headley – one of Boynton’s most eminent backers. Credit: Vanity Fair.

Between 1903 and 1907 George Boynton largely disappears from the record. Perhaps he was on the run from angry investors who had lost fortunes from his fraudulent businesses. It is also possible that he did in fact serve some jail time alongside Barnes, though we have no record of any such conviction. The most likely answer, as extraordinary as it may sound, is that Boynton saw an opportunity to return to his successful career as a mercenary soldier, this time in China. In subsequent interviews Boynton mentioned that he had served as a military advisor to the Japanese in Manchuria. We have no evidence to substantiate this claim, but the Russo-Japanese War, which lasted from February 1904 to September 1905, does conveniently fill the gap in our knowledge of Boynton’s activities.

The one reliable piece of evidence we have linking Boynton to the Russo-Japanese War is a passport application submitted to the U.S. Legation in Santiago, Chile in 1905. Boynton is said to have returned to the United States via Chile after serving in Japan, so there may be some credence to his claim after all. Either way, the Boynton North Pole Expedition which was scheduled to depart Spitzbergen in July of 1903 failed to come to fruition to the great disappointment of the American Geographical Society and to all of the “patriotic Americans” who supported him on his walk from New York to Colorado.

Darkest America Awaits

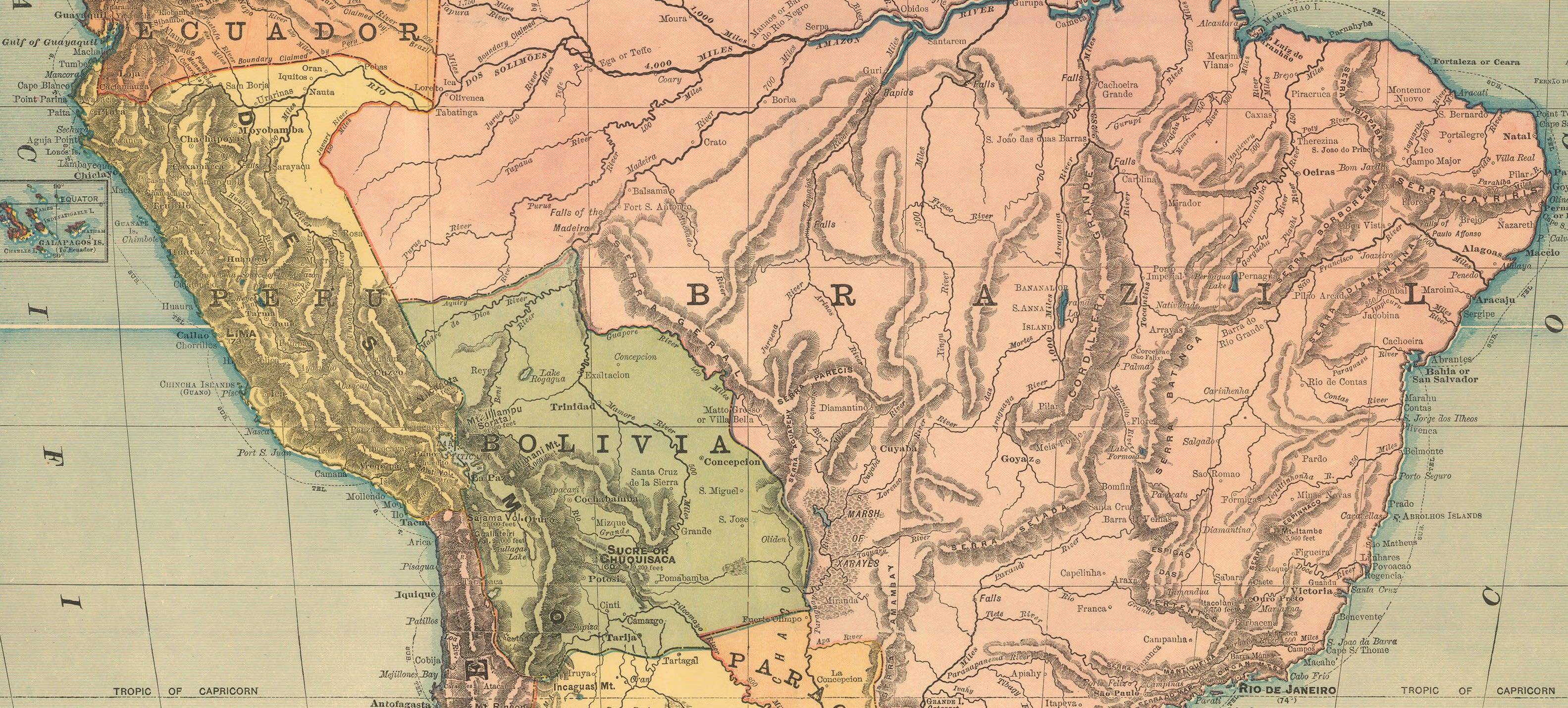

In the latter months of 1907 an article appeared in the New York Tribune heralding a new expedition to explore the interior regions of the South American continent. The newspaper received the information in a telegram from the Hotel Bellevue in Boston courtesy of the expedition’s organizer, Captain George M. Boynton. The news spread quickly and soon the expedition was being reported in newspapers as far afield as Sydney and Auckland. Boynton, having failed to walk around the world or fly to the North Pole, had clearly decided that the mysterious Amazon jungle was the next obvious choice for adventure, and not without reason. He certainly had experience traveling in South America from his early adventures as a mercenary. The South American interior was also beginning to garner a great deal of attention in the early years of the 20th century with fabled explorers such as Hiram Bingham and Percy Fawcett planning their own expeditions.

The Discovery Darkest America Expedition was named after the Discovery, the sloop Boynton had purchased to carry his explorers up the Amazon River, was expected to take place over five years. Starting from Pernambuco at the mouth of the Amazon, the expedition would follow the Amazon to its source before crossing the Andes to reach Punta Pariñas, Peru, the westernmost point in mainland South America. The earliest articles prominently mention the possibility of lost gold mines and potential riches for its members, but these claims were later dropped by Boynton in favour of the more plausible goal of scientific exploration.

The expedition was to consist of botanists, mineralogists, ethnologists, taxidermists, and photographers. Undiscovered flora and fauna were to be catalogued and sent back the greatest museums in London and New York. Dispatches from the expedition would be printed for the expedition’s supporters and were to be published in the Royal Geographical Society’s journal, unbeknown to the Society itself. Boynton had been elected a fellow of the R.G.S. back in 1902, but upon hearing of the expedition they categorically denied any association with Boynton or his undertaking. In the April, 1908 edition of its journal they flatly stated that they “had nothing whatever to do with the expedition” and that they “had no means of forming an opinion on the organization or objects of the expedition, or on the competency of its Commander.”

The extraordinary recruitment poster featured at the beginning of this article was likely printed in Boston in the early months of 1908 while Boynton was residing at the Hotel Bellevue. The Bellevue was one of the grandest hotels in the city and was given the honour of becoming the official headquarters of the expedition. A Boston newspaper reported at the time that Boynton would patrol the lobby of the hotel every morning and evening dressed in a khaki uniform, his chest covered in unrecognizable medals. Much to the annoyance of the hotel’s management and many of the guests, he would insist upon speaking at length to any likely recruits about the merits of the expedition.

The underlying map of South America was published by Rand, McNally & Co. map of in Chicago in 1906, but the text and the image of the Bellevue Hotel were overprinted on Boynton’s orders. This map was probably chosen for its bright colours and simple, approachable style. It also would have been relatively inexpensive. His experience publishing stock certificates to legitimize his sham companies would have given him a great deal of insight into the importance of good design to persuade investors. As Boynton’s funds were quite limited, this poster was probably printed in very small numbers and only distributed to important supporters or to groups such as the Explorer’s Club of New York of which Boynton was a member. The expedition’s logo, which does not appear on this poster but was used on letterhead and worn on Boynton’s uniform, was a “red and blue boa constrictor, superimposed on a skull and crossbones.”

The projected cost of the expedition was approximately $100,000, all of which would need to be raised by the members before departing. As mentioned on the poster, any “gentlemen who can provide their expenses and furnish satisfactory references” were invited to join the expedition. This invitation attracted the notice of at least one gentleman, a William Nutting of New York City, who paid $500 to become a member. Various other reputable gentleman were named in dispatches as prospective members, including Frederick Denham West who would serve as navigator and captain of the Discovery and Holliss Burgess, the son of a local yacht builder and Boynton’s second-in-command.

Boynton’s Downfall

Like all of Boynton’s earlier schemes, the Darkest America Expedition ended before it even began. Boynton left the Hotel Bellevue shortly after publishing the recruitment poster and in typical Boynton style he left a trail of unpaid bills behind him.

One of the aggrieved parties was Miss Bessie O’Brien, a stenographer at the Hotel Bellevue who had worked for the Captain for three weeks without receiving any pay and who had purchased 80 cents worth of stamps for his correspondence without any compensation. The press reported her story with special glee, going so far as to comment that she would have to give up her music lessons if she did not receive the pay she was owed.

His next destination was New York City where he hoped to find more willing recruits. Instead, he found himself locked in a jail cell for failing to pay another hotel bill, this time at the Hermitage Hotel at the corner of 7th Ave and 42nd Street. Boynton stayed at the Hermitage for 8 days during which time he had accrued a bill of $80 for meals and lodging. The manager, Mr. Bough, caught him on the ninth day trying to sneak out of the hotel and the authorities were called. He was arrested on the 20th of April and appeared in court the following day. To add insult to injury, it was revealed during the trial that he had also failed to pay his $48 bill for the khaki uniform and the medals he had worn in the lobby of the Hotel Bellevue.

It is worth a quick detour here to mention that the Manhattan prison in which Boynton was held overnight whilst awaiting trial had, by a remarkable coincidence, held another George Boynton just the year before. This man, Captain George B. Boynton, is the very same gentleman who had been filibustering his way around South America at the same time as our subject, George M. Boynton, back in the 1890s. He was arrested in 1907 by the Secret Service on charges of counterfeiting Venezuelan dollars and sentenced to several years in a New York prison. Luckily for Boynton, he was almost immediately pardoned by President Theodore Roosevelt, largely as the result of an amusing misunderstanding.

George M. Boynton, our subject, in his khaki uniform.

When some prominent New York citizens heard that a gentleman named George Boynton had been arrested in New York in connection with an outlandish scheme involving foreign currency, they reasonably (though incorrectly) assumed that it was their friend, George Melville Boynton, our subject. Letters from such distinguished individuals as the former mayor of Birmingham and Baron Headley, Boynton’s former business partner began to accumulate on the president’s desk appealing for a pardon.

President Roosevelt, every bit the adventurer himself, admired Melville Boynton’s spirit and granted the pardon. It was only when a lawyer visited George B. Boynton’s prison cell to deliver the pardon that the error was discovered. George B. Boynton was almost 30 years older than George Melville Boynton and sported a large, grey moustache, making it immediately obvious that a mistake had been made. The life of George B. Boynton is a remarkable tale in its own right, though not one that we have the time to discuss in detail here. His biography was published posthumously in 1911 as The War Maker.

Unfortunately for our hero, George Melville Boynton did not receive a pardon for failing to pay his hotel bill, possibly because his friends had already exhausted their influence obtaining a pardon for the wrong man. Either way, he was swiftly sentenced to three months of labour in a New York penitentiary, effectively crushing any realistic hopes that the Darkest America Expedition would proceed. Boynton, ever the optimist, stubbornly continued to promote the expedition after his release from prison. The final mention of the expedition appeared in a small central Florida newspaper on December 1th, 1908. The Ocala Evening Star reported that George Melville Boynton had arrived in St Petersburg on the West Coast of Florida to establish a training camp for his Darkest America expedition. The camp, which was to be “a model of its kind”, would be open to the public and donations would be gratefully accepted. Unsurprisingly, the camp was never built and the expedition was abandoned for good.

A Soldier once more

For six years after the disaster of the Darkest America Expedition Boynton disappeared entirely from the public consciousness. He finally reappeared in 1914 when the outbreak of the First World War provided an opportunity to return once more to his original career as a volunteer soldier. Boynton was living in London at the time and wasted no time in joining up. As a citizen of the United States, a neutral nation until 1917, Boynton’s options were limited. On the 13th of August, 1914, Boynton enlisted in the French Foreign Legion, one of the only forces to accept foreign volunteers at the time. Less than a month later he was on the front line in France and Belgium. He fought at the First Battle of the Marne and later at the Battle of the Aisne. After six months of fighting he was wounded by a shell in Flanders and sent back to London to recuperate.

Fortunately, the injury must have been mild as he spent less than a month in London before returning to action, this time as part of the East Africa campaign. On the 6th of May, 1915 Boynton arrived in Mombasa, Kenya as a private in the 25th Royal Fusiliers. This battalion, more commonly known as the Frontiersmen, consisted largely of men who were too old to fight elsewhere but who had extraordinary experience as soldiers or adventurers. Boynton, now 45 years old, was an ideal recruit for the Frontiersmen and blended in perfectly with the odd assortment of big-game hunters, cowboys, explorers, and French Foreign Legionaries which made up about half of the battalion. The Frontiersmen were the only British troops sent into combat during the war without any formal training, a testament to their abilities and the esteem with which they were regarded. The battalion’s leader, Frederick Courtney Selous, was a famous big-game hunter who provided the inspiration for the character Allan Quatermain in the H. Rider Haggard’s famous novels.

British Army map of Mombasa to Mount Kilimanjaro published during the First World War. (click to see the full map)

British Army map of Mombasa to Mount Kilimanjaro published during the First World War. (click to see the full map)

By the autumn of 1917 he was back in the United States where he spent the rest of the war giving talks about his experiences in France and Africa. The tales he recounted of the brutality of the East African campaign were particularly shocking to many of his American audiences. After the war ended he continued to tour the country while attempting to raise money for a home for disabled veterans in his hometown of Laconia, New Hampshire. On several occasions he was refused permission to speak and told by the authorities to leave town when the locals became suspicious that he might be a fraudster. It seems that he may have lost some of his youthful charisma with the onset of middle age.

One final chance at glory

Boynton’s swansong, his final attempt at immortality, came in 1924 when he announced to the press that he was planning another expedition, this time to Central America. The goal of the expedition was to find the lost Aztec city of Bacis which was rumoured to be covered in gold and treasure. He claimed to have heard about the location of the city whilst fighting alongside President Álvaro Obregón of Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. The expedition was to consist of 24 members, including, for the first time on one of Boynton’s expeditions, a woman. Miss Mayme Williamson, a former army nurse who had served during the Great War, was recruited for her medical expertise and for her skills as an artist. Like all of Boynton’s previous endeavours, the expedition never launched and was quietly abandoned.

Boynton with Mayme Williamson. Credit: The Southington News, April 17th, 1924

George Melville Boynton lived in San Francisco for the remaining twenty years of his life. How he supported himself is not clear, though he continued to list his occupation on California voter rolls as ‘military advisor’ until he was in his late 60s. He died sometime in the mid-1940s, alone and largely forgotten. If any of his planned expeditions had succeeded he would have ranked among the greatest explorers of the age. Instead he left behind a legacy of failure, broken promises, and defrauded investors. We should, however, remember that he was not without accomplishments. He successfully walked across the United States at least twice, he fought bravely on two fronts in the First World War, and he developed a loyal network of friends who were willing to petition the President of the United States for a pardon on his behalf. One of the greatest ironies is that if he had stayed in New York as a young man and ignored his desire for adventure, he would have inherited his father’s successful tailoring business and become a millionaire by legitimate means. Instead he chose to live an extraordinary life.