It was March 1824 when the first Anglo-Burmese war began. The Governor General of India had declared war on Burma after they had invaded Assam for the third time.

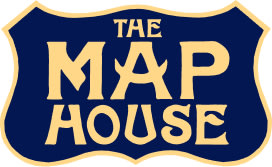

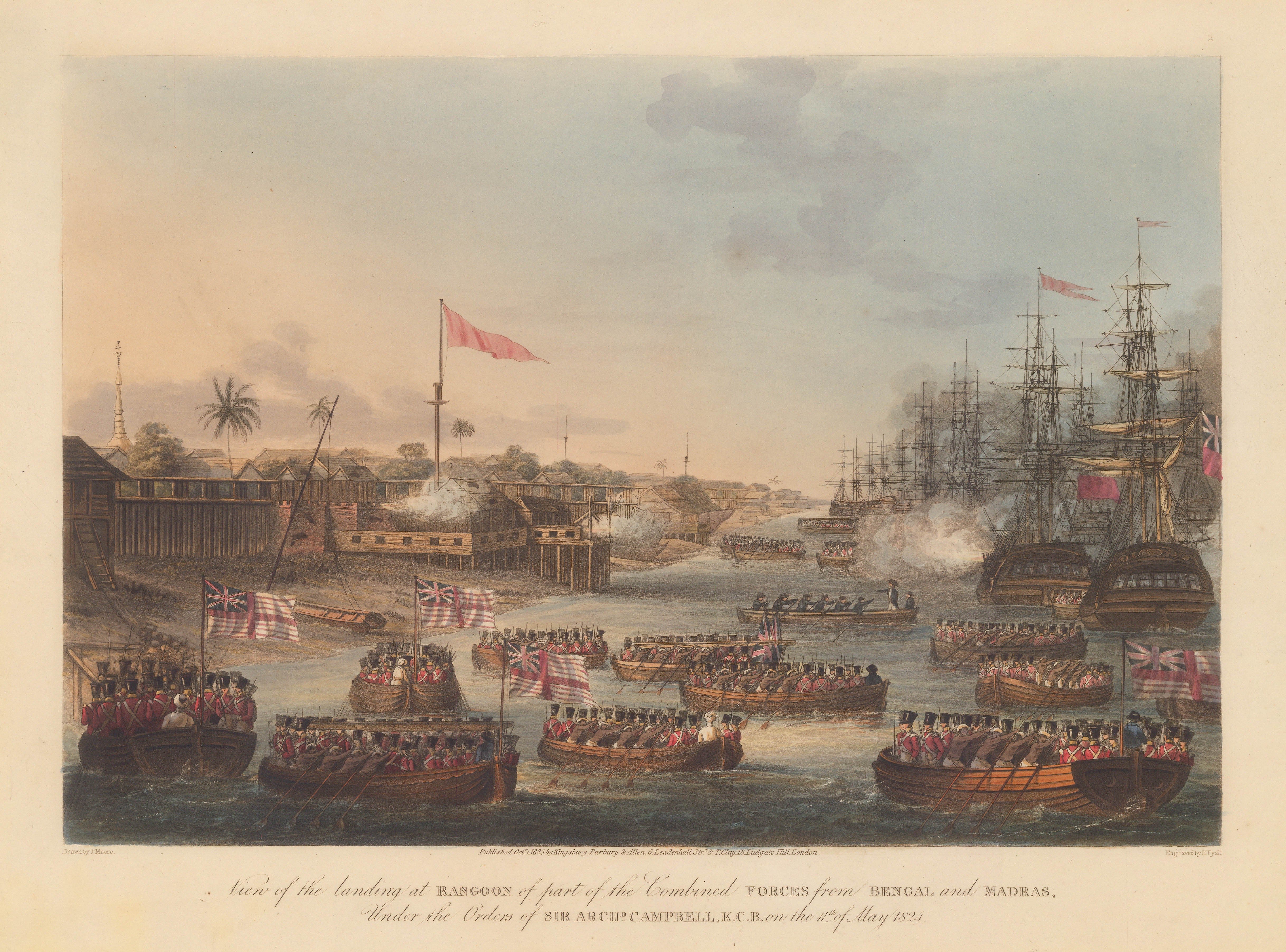

This resulted in Major General Archibald Campbell and Naval Captain Frederick Marrayat leading the British Expeditionary Force and Naval regiments, an army of 11,000 strong, to Burma where they descended upon Rangoon (now Yangon), the principal sea port of the Burmese Empire and took position in the fortified Shwedagon Pagoda compound.

Plate 1: Port Cornwallis, Great Andaman: Harbour scene with the British fleet including the steam powered warship HMS Diana, the 50 gun HMS Liffey and the Napolianic war cruizer class sloop HMS Sophie.

Plate 1: Port Cornwallis, Great Andaman: Harbour scene with the British fleet including the steam powered warship HMS Diana, the 50 gun HMS Liffey and the Napolianic war cruizer class sloop HMS Sophie.

Plate 2: The landing of the combined forces of British Infantry, Bombay Marine and the East India Company’s private arrmies from Bengal and Madras.

Plate 3: Great Dagon Pagoda as seen from the principal approach with the Bombay Marine in marching formation.

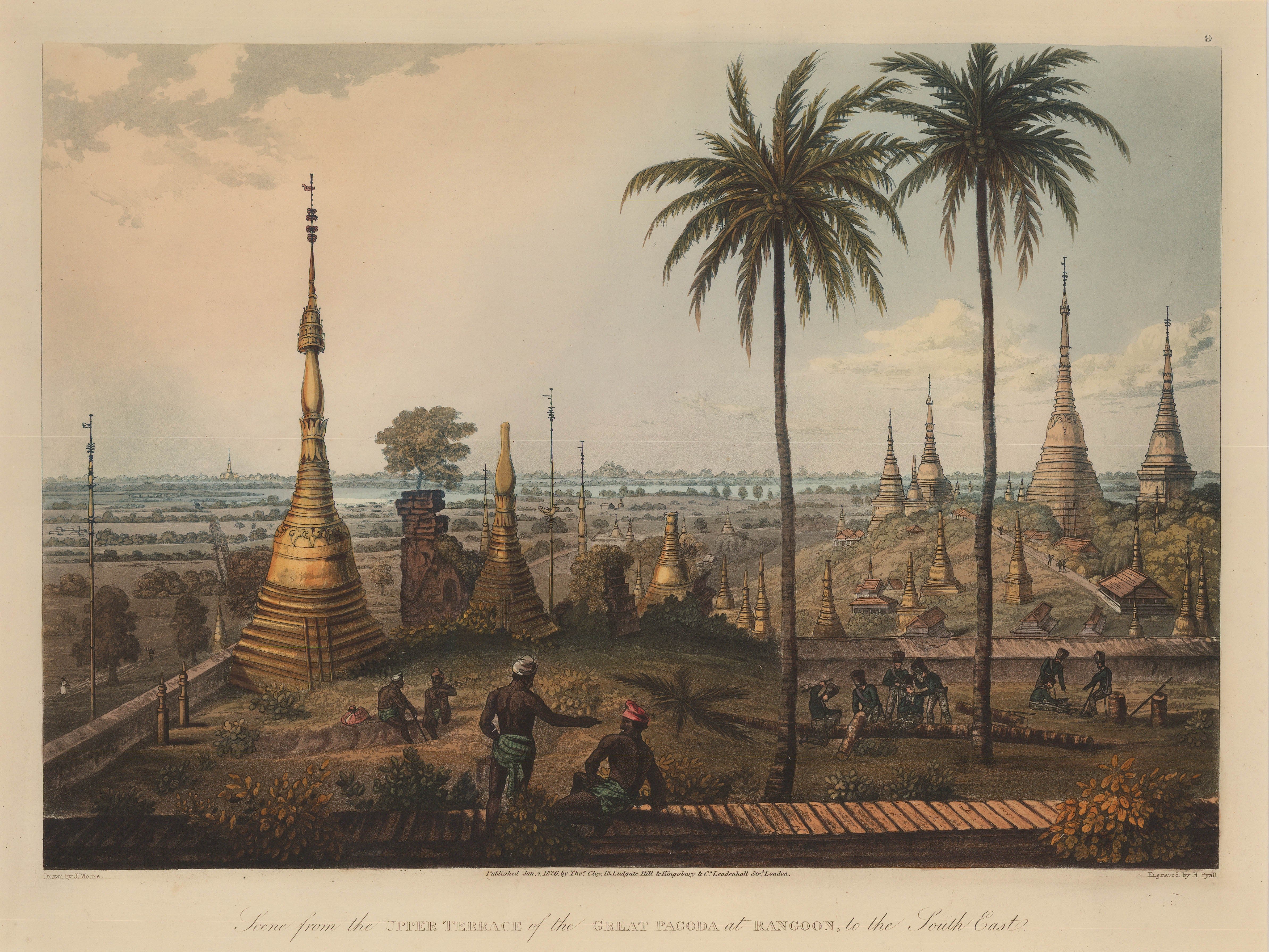

Among the 6,000 British and 5,000 Indian men were Lieutenant Joseph Moore and his comrade R. B. Graham, serving with the 89th Regiment. They decided to document their time by making sketches of the realities of war juxtaposed against the beautiful and exotic back drop of Burma. These sketches were later turned into a series of eighteen aquatints. It was a fairly common practice for soldiers to record their time during war or on expedition, and like centuries of men who had made visual recordings of their moments in battle, little is known about them save for these superb prints. These are the first large-scale views available of Burma, a previously unknown area to the British eye. A year after these prints were published, Captain Marrayat published his own series of six plates.

Plate 4: Great Dagon Pagoda from the Great Road with a native fishing in the foreground.

Plate 4: Great Dagon Pagoda from the Great Road with a native fishing in the foreground.

Plate 5: Great Dagon Pagoda: Idyllic scene during the First Anglo-Burmese War. From the first large scale work of Burma.

Plate 6: Dramatic scene of the attack on the stockades with a Company observer beneath an umbrella.

The printing method used in this series is aquatint. The aquatint is a form of copper engraving created by Dutch painter and print-maker Jan van der Velde during the mid 17th century. The process was later developed by French etcher and painter Jean Baptiste Le Prince in the 1760s in Paris, and in 1770, passed on to his understudy Paul Perez Burdett, a British cartographer and printmaker. Burdett taught and sold the process to Paul Sandby who coined the term “Aquatint”. Although the medium became favoured by many continental masters, it was English etchers who employed it most elaborately as an expression of the Cult of the Picturesque, an aspect of The Romantic Movement. This new technique enabled much greater atmospheric variety to be achieved, recreating the tonal complexities and textures of paintings.

Plate 7: Eastern prospect of the Gold Temple of Guadma.

Plate 7: Eastern prospect of the Gold Temple of Guadma.

Plate 8: Interior view of the Gold Temple.

These views are a contrast of battle scenes in a seemingly unassuming paradise. The towering golden Pagodas and glorious Temples against the creamy-dusky skies of Rangoon, paired with views of violence and fire-power. The prominence of the British Imperial red uniforms and triumphant flags in amongst the smoke of battle give a sense of tension within these idyllic landscapes. The exquisite detailing of these aquatints adds to the dreamy quality of the views overlooking Rangoon – making a truly attractive picture. Aquatints also gave the artist more freedom to detail the sky. Before with methods such as woodcuts and copper engraving, the sky was kept to a minimum as it could only be expressed as cross-hatching and pressurised engraving. The introduction of aquatint lead to a lowering of the horizon, as the artists were able to describe the sky and create an atmosphere more accurately.

Plate 9: Great Dagon Pagoda. View from the upper terrace towards the South East with British soilders felling trees in the foreground.

Plate 9: Great Dagon Pagoda. View from the upper terrace towards the South East with British soilders felling trees in the foreground.

Plate 10: Dramatic scene of the Army storming a lesser stockade at Kemmindine.

Plate 11: Inya Lake and the Eastern Road at the advance of the 7th Madras Native Infantry.

Joseph Moore romanticised the First Anglo-Burmese war of 1824-26, despite it being the most expensive campaign in British Indian history and subsequently leading to a severe economic crisis there in 1833. In England, these aquatints would have been passed around as a collection for the middle to upper class in England, bound within a plate book, with the intention of showing them off and creating a particular imaginative atmosphere in tune with the ‘Cult of the Picturesque’. They will have also given the viewer the impression of security in wars abroad as they depict British regiments carrying out their duties without impediment.

Plate 12: The Army in formation with the earliest depiction of a Congreve Rocket, developed By Sir William Congreve in 1804.

Plate 12: The Army in formation with the earliest depiction of a Congreve Rocket, developed By Sir William Congreve in 1804.

Plate 13: Looking South from the Eastern Road towards the Rangoon River.

Plate 14: Shwedagon Pagoda during the First Anglo-Burmese War. Showing a subsitute for the world’s heaviest bell cast in 1484 and sunk in the Yangoon during its theft by Portugese mercenaries in 1608.

Many of the scenes are tranquil and offer insight into the soldiers’ experiences, absorbing and appreciating their new surroundings and the cultures of Burma. The serenity of some of the views between scenes of battle offers a calm-before-the-storm affect to the viewing of the pieces. Plate books and print collections like these were the Instagram of their day, capturing a moment in time for other people to try and create an impression, albeit glamorised, of what it was like to be there.

Plate 16: Dramatic scene of the Army battling to gain the principle stockade.

Plate 16: Dramatic scene of the Army battling to gain the principle stockade.

Plate 17: Great Dagon Pagoda as seen from the Eastern Road.

Plate 17: Great Dagon Pagoda as seen from the Eastern Road.

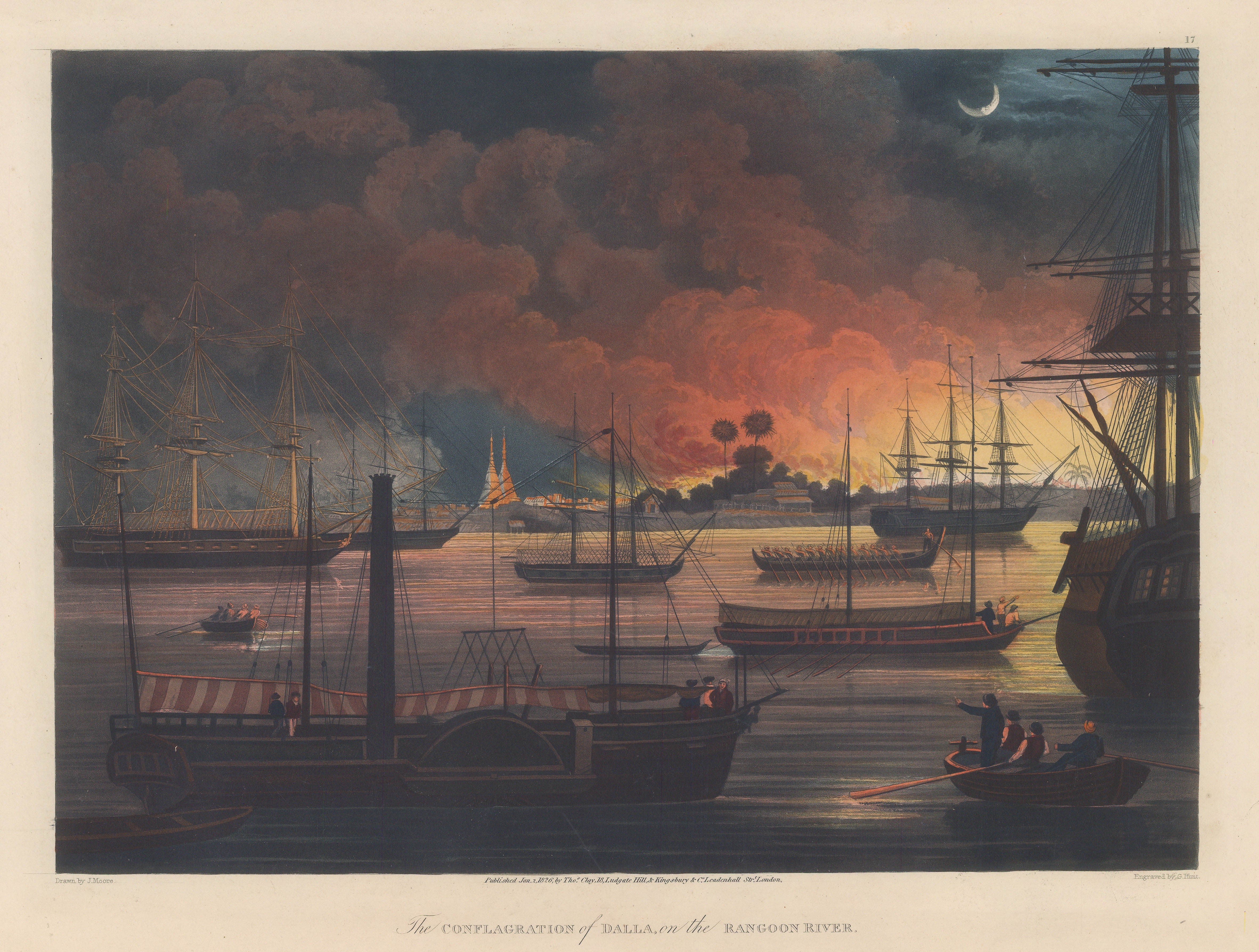

Plate 17: View of the burning plain of Dalla with the British Fleet in the harbour including HMS Diana, the first steam powered warship of the East India Company, newly armed with Congreve rockets.

Plate 17: View of the burning plain of Dalla with the British Fleet in the harbour including HMS Diana, the first steam powered warship of the East India Company, newly armed with Congreve rockets.

Plate 18: Dramatic scene of General Campbell and the Bombay Marines attacking the stockades.

The British claimed military victory in 1826. Despite this triumph, it was a financially devastating war for both parties. Burma’s huge reparation bill of 1 million pounds effectively bankrupted its Royal Treasury. The British Indian alliance also went into economic turmoil, contributing to the Indian economic crisis of 1833. That in turn led to the removal of the remaining monopoly privileges of the British East India Company’s trade in China. The British-Indian army went on to fight two more wars against a now weakened Burma, in 1852, where they seized the entire lower-half of the country, and in 1885-1886 when the British annexed Burma in its entirety.

About the author

The Map House

Plate 16: Dramatic scene of the Army battling to gain the principle stockade.

Plate 16: Dramatic scene of the Army battling to gain the principle stockade.

Plate 17: View of the burning plain of Dalla with the British Fleet in the harbour including HMS Diana, the first steam powered warship of the East India Company, newly armed with Congreve rockets.

Plate 17: View of the burning plain of Dalla with the British Fleet in the harbour including HMS Diana, the first steam powered warship of the East India Company, newly armed with Congreve rockets.