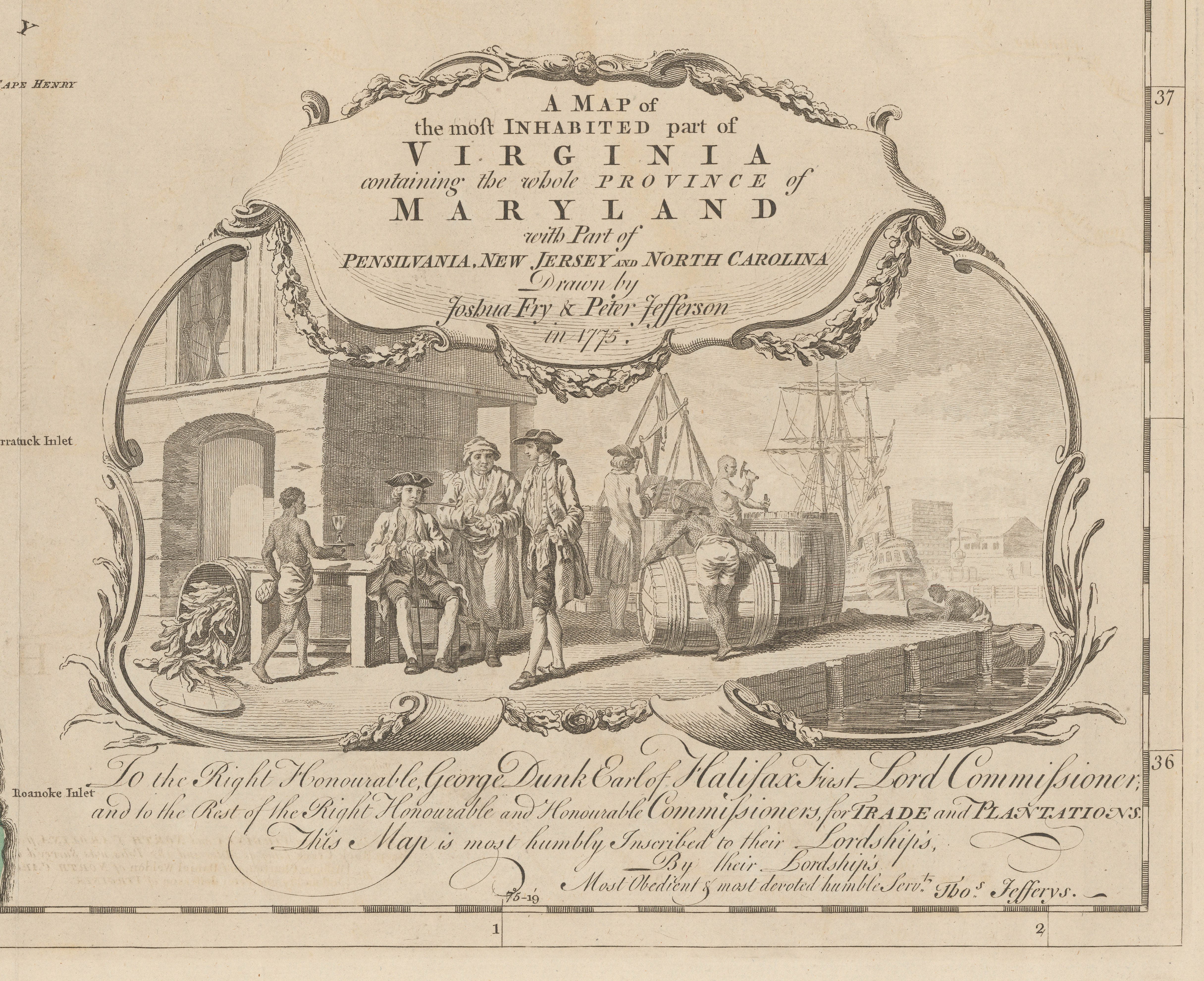

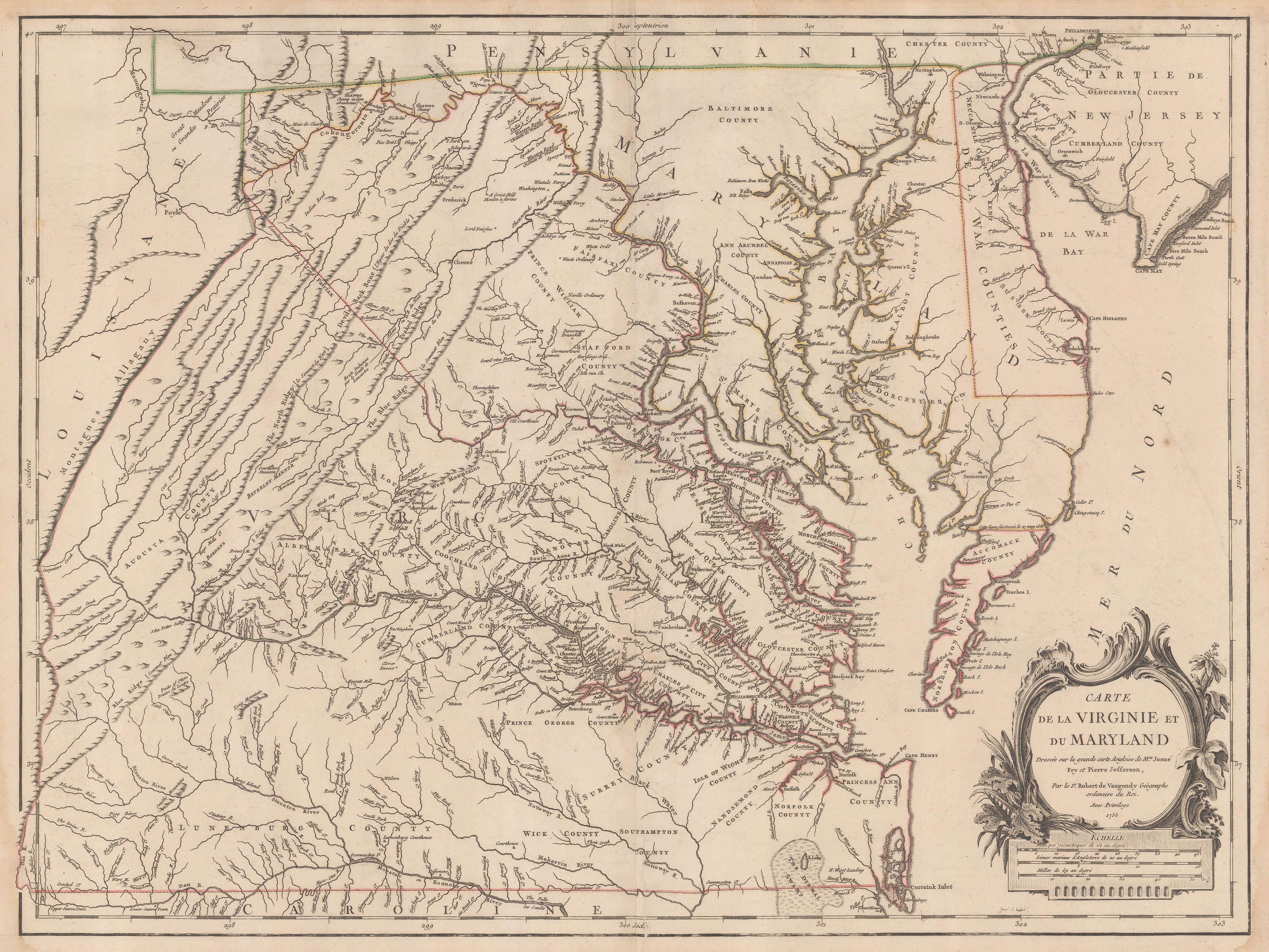

2 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Fairfax line [USA6107]

2 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Fairfax line [USA6107] 3 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, North Carolina and Virginia border [USA6107]

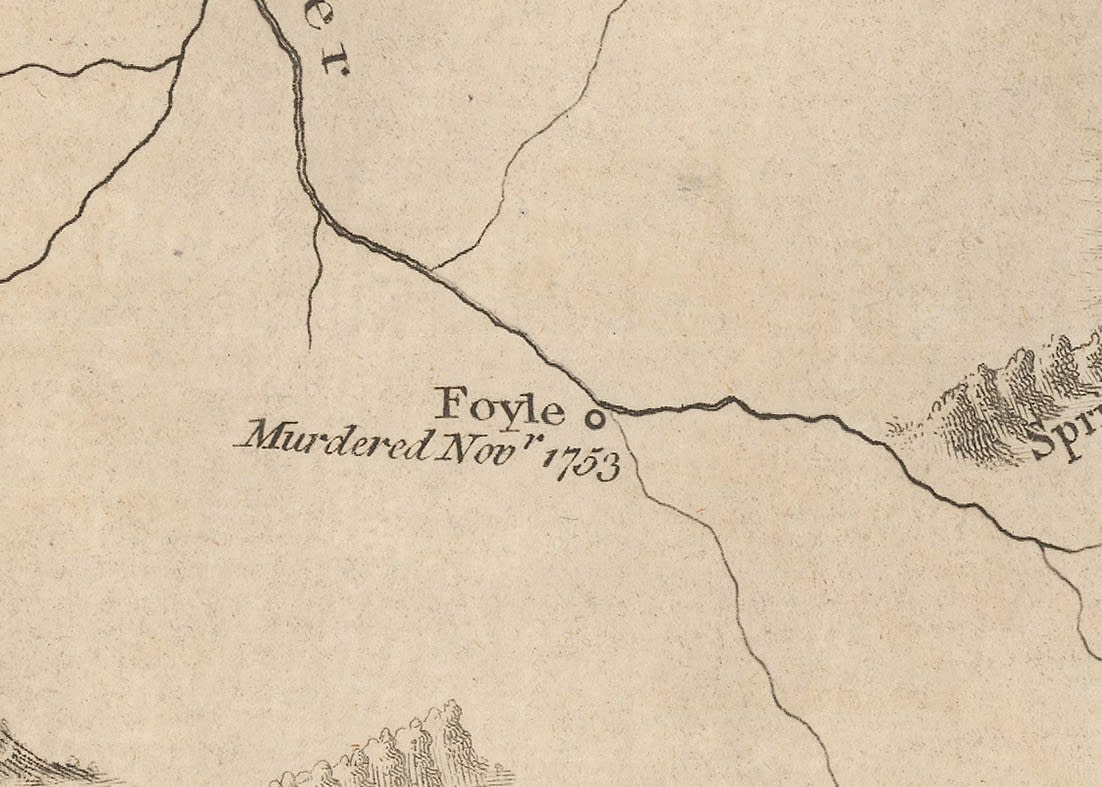

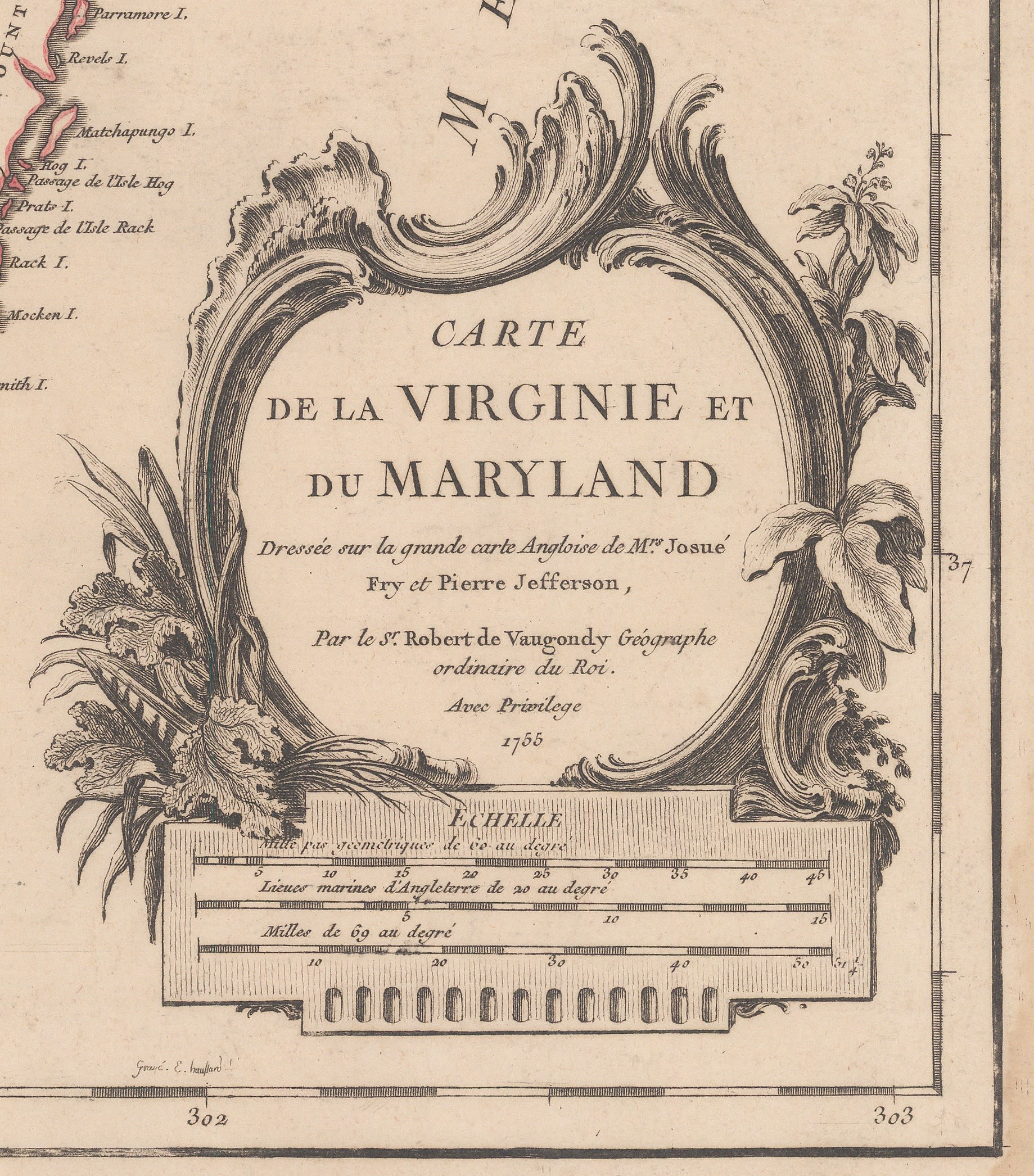

3 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, North Carolina and Virginia border [USA6107] 4 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Cartouche [USA6107]

4 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Cartouche [USA6107]

|

|

|

5 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Westover Plantation [USA6107] |

6 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Little Hunting Creek Plantation [USA6107] |

The map also makes an emphasis of marking the possessions of the Fairfax family, including their "fine lands" as well as their "manor" and plantation. Anne Fairfax was Lawrence's wife. Their household would become one of the foremost gathering places of Virginia frequented by the great and the powerful of the Colony. Aided by his father in law, Lawrence would become the founder of Alexandria as well as one of the founder members of the Ohio Company.

7 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Fairfax Manor, and Plantation [USA6107]

7 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Fairfax Manor, and Plantation [USA6107]

As soon as the map was finished, it was given to Governor Burwell who forwarded it to London. Fry and Jefferson were paid 150 pounds each for their role.

Publication History

Once in London, the map was entrusted into the care of the experienced Thomas Jefferys, cartographer to the Prince of Wales later George III. He began preparation for its publication; it took approximately two years to prepare the first issue. Although the first edition of the map bears the date 1751, it was not published until probably 1753; it is not known what caused the delay although it is likely that the British government and the Board of Trade would have needed a substantial amount of time to study and deliberate over this newly acquired geographical information.

Another edition was published shortly after, in 1754 and two more were issued in 1755. These first four editions bear substantial geographical revisions and additions, particularly the last edition of 1755, sometimes known as the "Dalrymple edition".

The Dalrymple Edition

These particular updates were provided by additional information forwarded by Joshua Fry and Christopher Gist, gathered from a new expedition to western Virginia in 1752. Captain John Dalrymple, quartermaster to this expedition, was a further donor of vital information to this new issue and also acted as a courier for the updates which reached the government in London in 1754.

These new additions are acknowledged on a panel on the north western sheet on subsequent editions. There were four further editions after this but without geographical change; the only differentiation on these is the address and date of publication recorded on the map.

8 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Gist and Dalrymple additions [USA6107]

8 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Gist and Dalrymple additions [USA6107]

The first four editions were published as separate publications, or single sheets; their survival depended on being backed on linen and segmented or bound in composite atlases of private collections. Today, they are generally not available to collectors due to their rarity.

The example we showcase in this article is state or edition 6 which appeared in the posthumous "North American Atlas" compiled by Thomas Jefferys but published by Robert Sayer in 1775.

French and English claims in North America

The publication of Fry and Jefferson's map did not go unnoticed abroad; particularly in France. The French and English governments had an ongoing dispute about the distribution of land in the interior of North America. The French grudgingly acknowledged the English presence on the East coast but in 1718 Guillaume de L'Isle published both a landmark and infamous map of Louisiana which showed its northern border reaching New France or Canada, uniting the Gulf coast in the south to the Canadian hinterland in the north under French rule. This infuriated the English, both in North America and England and several English maps were issued disputing this claim. A particularly famous example is Hermann Moll's map of the United States which highlighted these claims and "invited Noblemen, Gentlemen, Merchants &c who are interested in our Plantations in these Parts, may observe whether they agree with their Proprieties or do not justly deserve ye name of Incroachments;"

9 - United States - Herman Moll c. 1730 [USA9445]

9 - United States - Herman Moll c. 1730 [USA9445]

10 - United States - Herman Moll c. 1730 - Detail, encroachment cartouche [USA9445]

10 - United States - Herman Moll c. 1730 - Detail, encroachment cartouche [USA9445]

The western extent of English colonies was initially a vexing question for the government since they would possibly encroach not only on French but also on Spanish possessions, but by 1732, George II granted General Oglethorpe the right to establish the new colony of Georgia theoretically extending from the Atlantic coast in the east to the Pacific coast in the west. In reality, the English would never be able to support a claim of land ownership stretching from coast to coast but it did lead to Emanuel Bowen's famous map of Georgia, the first map of the new colony, showing its western border reaching the Mississippi River and possibly beyond, published in 1748.

11 - Georgia - Emanuel Bowen, 1748 [USA9353]

11 - Georgia - Emanuel Bowen, 1748 [USA9353]

In 1755, John Mitchell, in his authoritative map of the British possessions in North America bore several panels of text quoting early 17th century English charters which stated that the western borders of New England and Virginia extended to the South Sea or Pacific Ocean.

Vaugondy's 1755 Edition of the Fry Jefferson Map

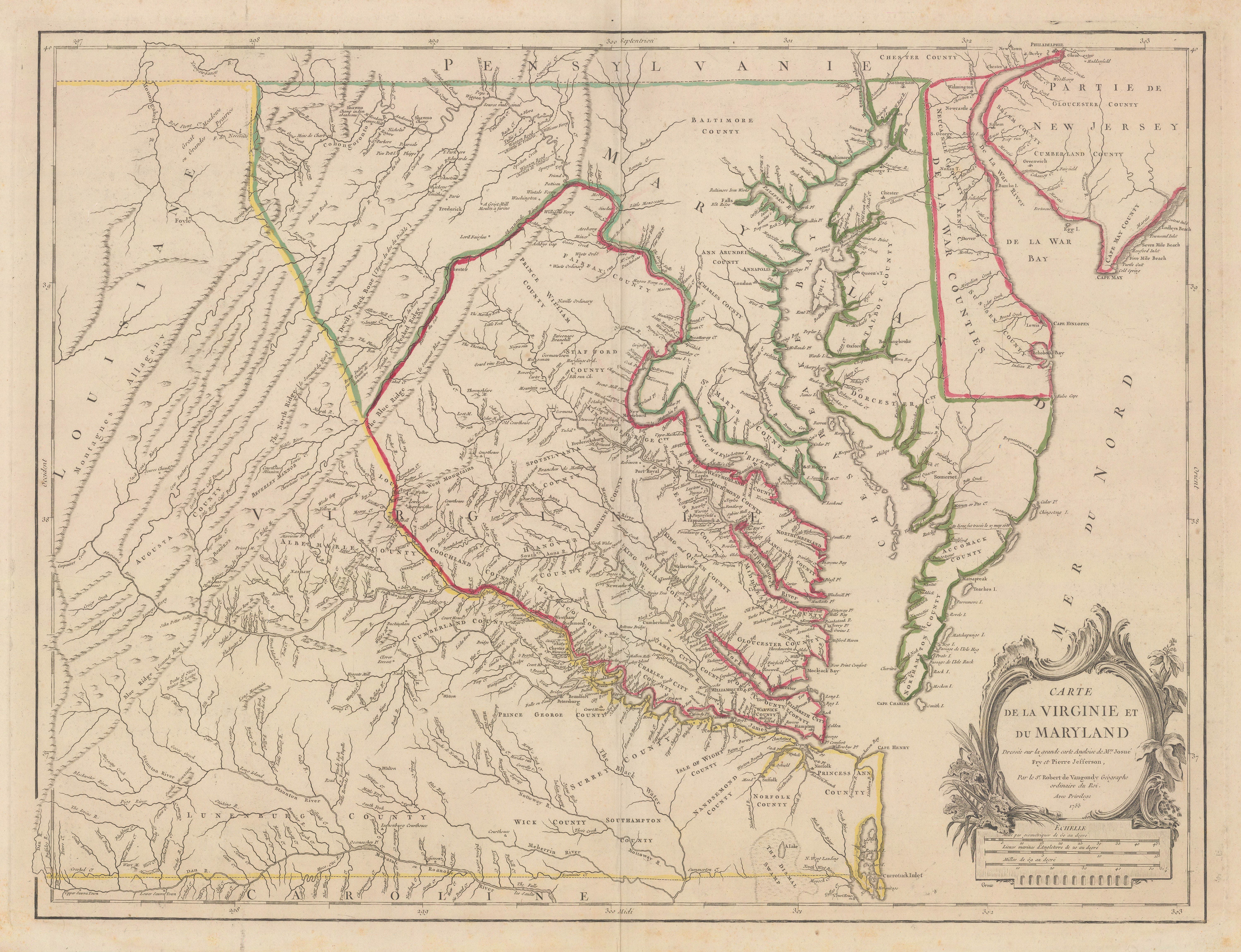

Coincidentally, in the same year, Robert de Vaugondy engraved a French version of the Fry Jefferson map of Virginia.

12 - Virginia - Vaugondy 1755 [USA9487]

12 - Virginia - Vaugondy 1755 [USA9487]

The de Vaugondy firm of father and son were a successful commercial firm of cartographers in France. Gilles Robert de Vaugondy was born in 1688 and although little is known about his early life, by 1719, there is a record of his occupation as "geographe" on his marriage certificate. His son, later partner and main collaborator Didier, was born in 1723. In 1730, Vaugondy received a major boost when Pierre Moullart Sanson, grandson of Nicholas Sanson, the father of French cartography, willed the Sanson archive to Vaugondy and two of his colleagues, Jacques Perrier and Jean Fremont. The estate included a house which served as financial collateral to finance the firm's early cartographic projects. Perrier liquidised his holdings fairly early in the partnership, leaving the firm in the hands of Gilles and Jean Fremont. Fremont was in charge of the finances. Although the firm's profits were not spectacular, they were solid and more importantly, they stayed solvent. A further boost to the confidence of the firm was the granting of the title "Geographe Ordinaire du Roi" to Gilles in recognition of his expertise in globe making. This enabled him to add this title to all his maps in the cartouche, announcing royal recognition of his work. It is not known if this title gave him additional access to government archives but it must have helped in his networking and promotion.

Vaugondy's first atlas was the highly popular "Atlas Portatif et Militaire", a small compact work issued in 1748. It proved such a success that an expanded edition was issued in 1749. It also encouraged the firm to embark on their most ambitious project, the "Atlas Universel" which began preparation in 1750. It was a large folio work combining the precision so prized by French cartographers and pioneered by Nicholas Sanson. However, in a nod to popular taste, Vaugondy added a certain level of decoration to the maps which was not encouraged by their more academic contemporary colleagues such as D'Anville and Buache. This was in the form of finely engraved cartouches.

The atlas was issued in parts by subscription and was finally completed in 1757; within the section focused on the New World, is the map of Virginia based on Fry and Jefferson mentioned above.

The cartouche gives Fry and Jefferson full credit: "Carte de la Virginie et du Maryland, dressee sur la grande carte Angloise de Mrs Josue Fry et Pierre Jefferson". They are mentioned by name which was unusual for the atlas. None of the other maps bear this distinction. On the surface, the maps look the same, particularly if one matches the geography. Although the map has been reduced to be bound into a folio atlas, it still bears the same details, including the name of the plantation owners and the locations of their homes, the names of the counties as well as the newly discovered geographical detail in the west although Vaugondy omits to add the names of Gist and Dalrymple. There are some minor differences: the name Belhaven is present but not its alternative, Alexandria; in northwest Virginia, Frederic substitutes the names Fredericktown or Winchester on the original Fry and Jefferson map; but broadly speaking, Vaugondy follows the geography of the English map quite closely.

13 - Virginia - Vaugondy 1755 - Detail, cartouche [USA9487]

13 - Virginia - Vaugondy 1755 - Detail, cartouche [USA9487]

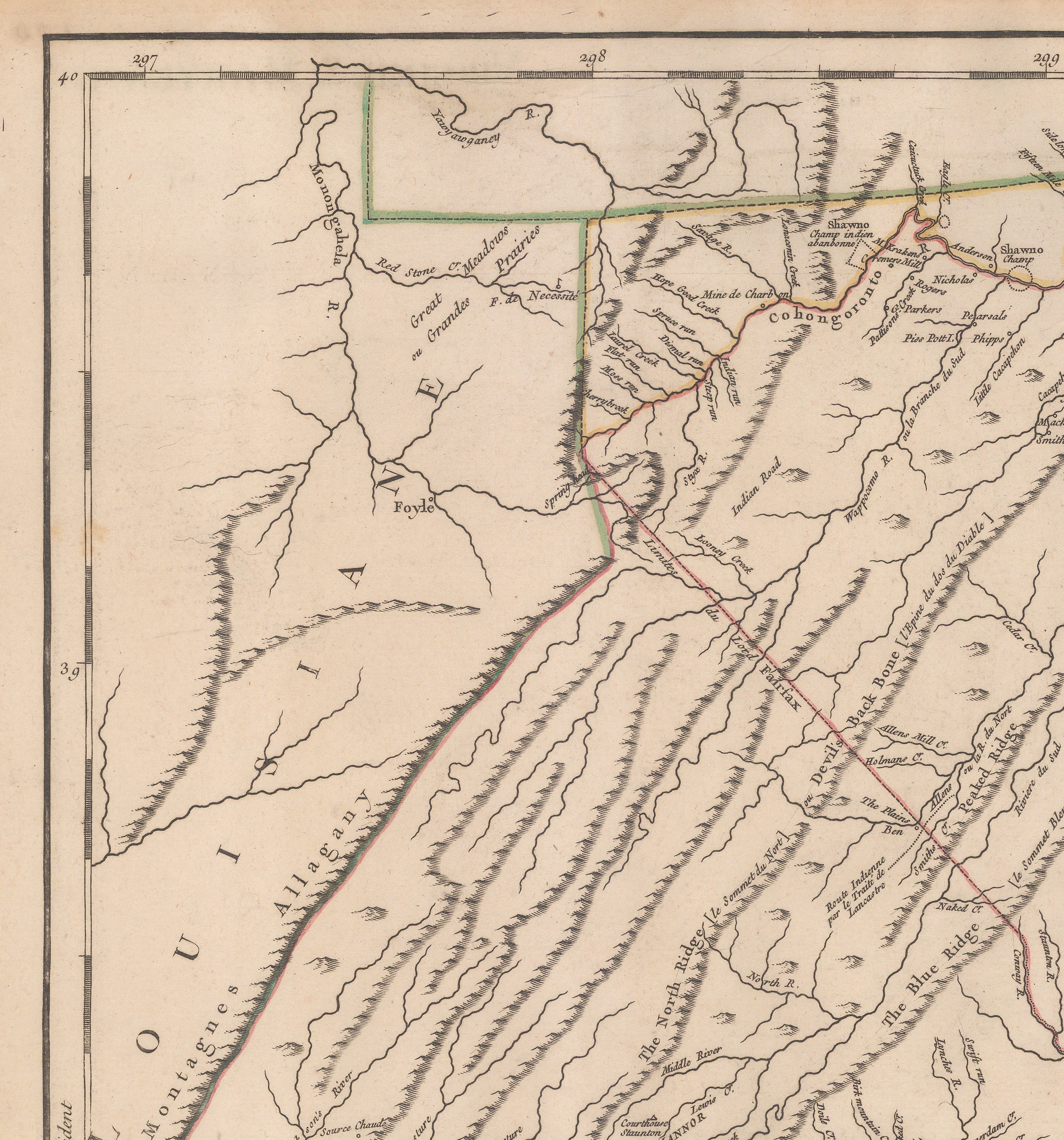

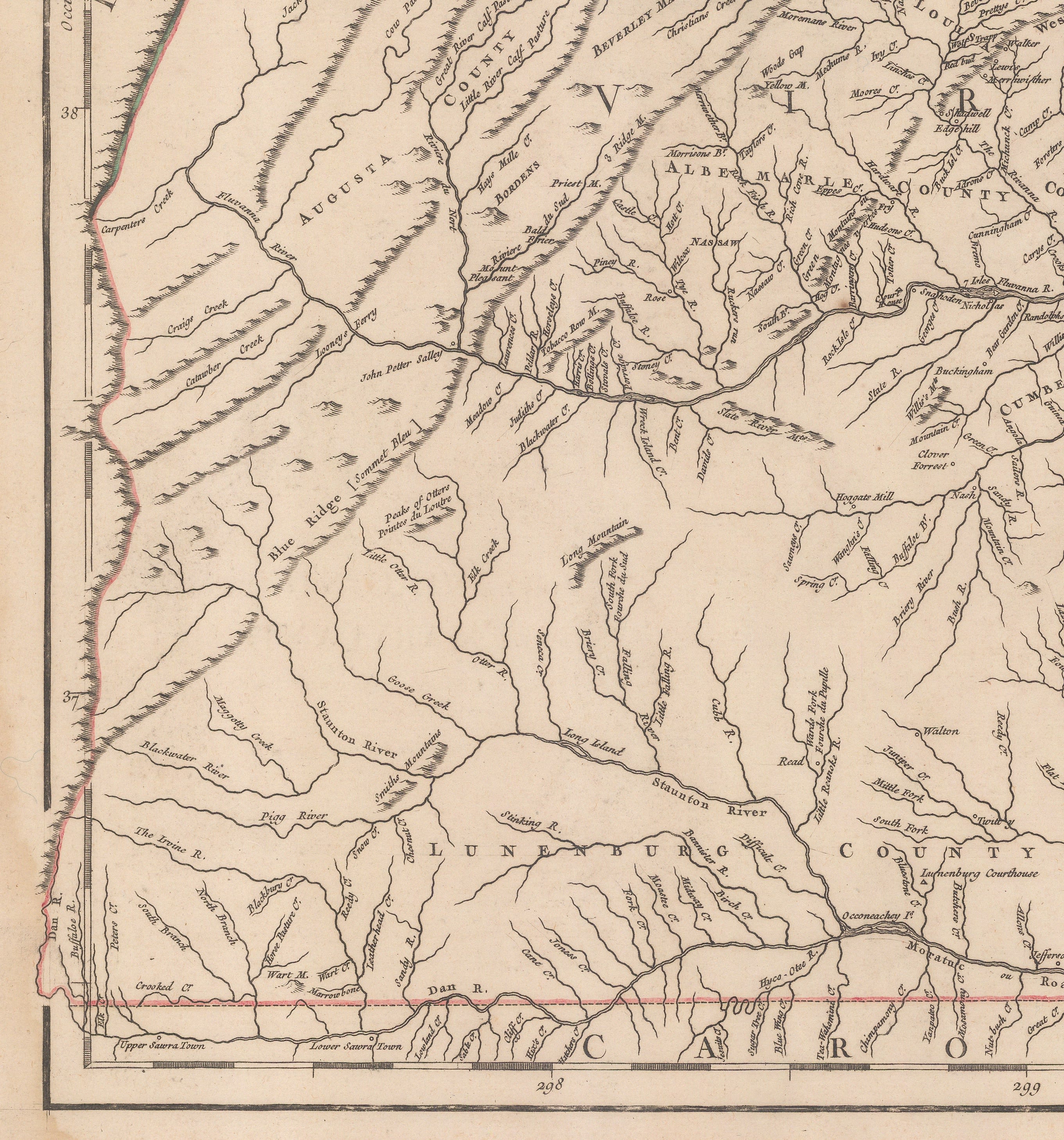

Geopolitically however, there are crucial differences. The first is their use of original colour. On the Fry and Jefferson map, the colour is quite subdued and does not extend to the far west; it is mostly confined to the delineation of rivers or sea shore. It is also used to note only the borders between Virginia and North Carolina and Maryland and Virginia. The border between Maryland and Pennsylvania is vague. The Fairfax Line in the northwest is left uncoloured.

On the Vaugondy map, the colour is far more prominent. The bright, bold reds, greens and yellows clearly delineate the divisions between Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and the Fairfax Land.

Crucially, Vaugondy also adds one final border. In the west, a line runs along the Allegheny Mountains, adding a western border to Virginia which is not present on the original Fry and Jefferson map. To emphasize this change, Vaugondy adds the name "Louisiana" beyond this line.

|

|

|

14 - Virginia - Vaugondy 1755 - Detail, western border (north) [USA9487] |

15 - Virginia - Vaugondy 1755 - Detail, western border (south) [USA9487] |

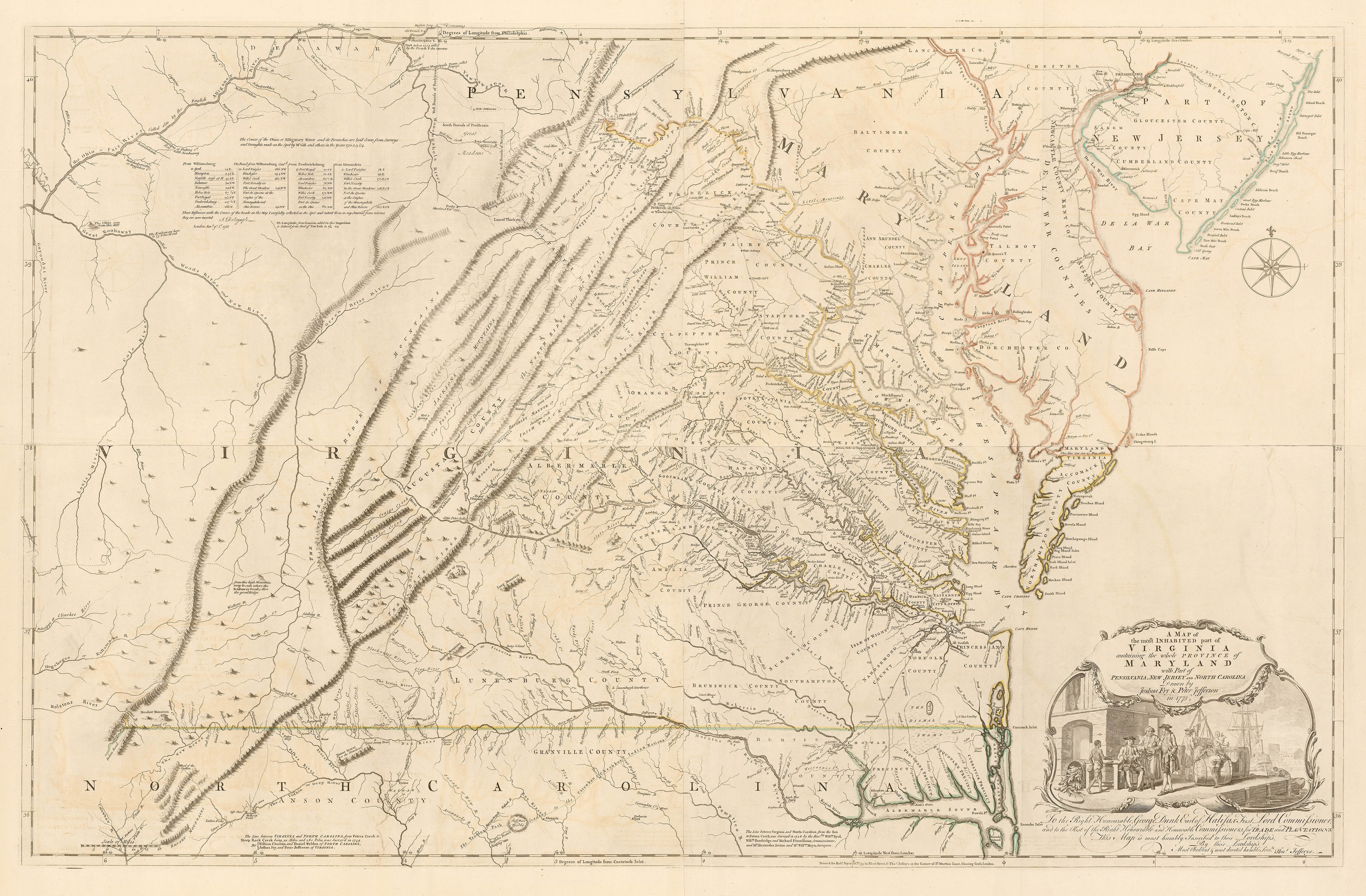

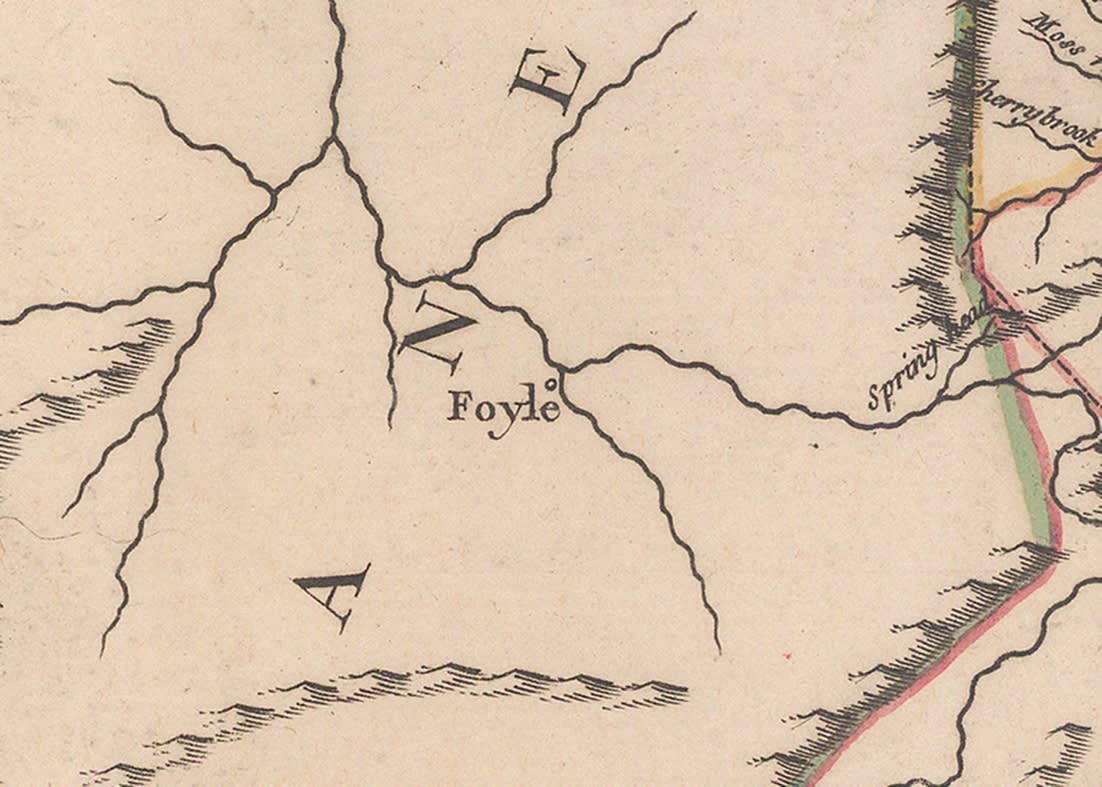

There is one more highly interesting change. Possibly the westernmost homestead on both maps is marked as "Foyle". This is a reference to the settler Robert Foyle.

In 1753, a raid by the Ottaway Indians, allies of the French in North America, attacked his homestead and killed him, his wife and five of their six children. This is perceived as one of the flashpoints which initiated the French Indian War.

On the Fry Jefferson map, the homestead is marked together with a note: "Foyle murdered Novr. 1753." The Vaugondy map just bears the name "Foyle" with no accompanying note. This suggests a very careful perusal of the Fry and Jefferson map together with a selective dissemination of information to the French public.

|

|

|

|

16 - Virginia - Fry Jefferson 1775 - Detail, Foyle Homestead [USA6107] |

17 - Virginia - Vaugondy 1755 - Detail, Foyle Homestead [USA9487] |

Publication history of Vaugondy's map

18 - Virginia - Vaugondy c.1776 [USA9551]

18 - Virginia - Vaugondy c.1776 [USA9551]Vaugondy's Virginia - 2nd State