The ‘Sport of Kings’ was first brought to Great Britain by the Romans. Originally a spectacle for the public, racing continued as a largely private event for centuries after the Romans’ withdrawal.

In the earliest days the owners, the majority of whom were aristocrats, rode their own horses ‘inspired with the thought of applause and hopes of victory’. As racing became more organised they tended to employ their grooms, and so the events widened to include servants and their families. Thus in contrast to other sports and to Europe as a whole, racing meets in Britain saw the intermixing of participant and attendee, commoner and grandee. Racing enjoyed royal patronage through successive Monarchs, save for the reign of Elizabeth I when for unknown reasons it fell into disfavour despite her being a keen horsewoman and attending meets at Croydon.

Duke of Newcastle:: Balottades par la Droite. 1743. An original copper engraving. Not published in English until 1743, the influential treatise on Equitation by the Duke of Newcastle was written in 1658 whilst he was in exile in Paris during the Interegnum.

In the reign of James I, racing returned to favour and the first formal racing meet was held in 1622 between the Marquess of Buckingham and Lord Salisbury at Newmarket. Meets grew in popularity from then until being banned by Oliver Cromwell along with other grievous enjoyments such as Christmas and public kissing. Charles II restored the ‘sinful’ sport and not only set the first recorded rules for a race, the newly created Newmarket Town Plate but won it himself in 1671, the only monarch ever to do so.

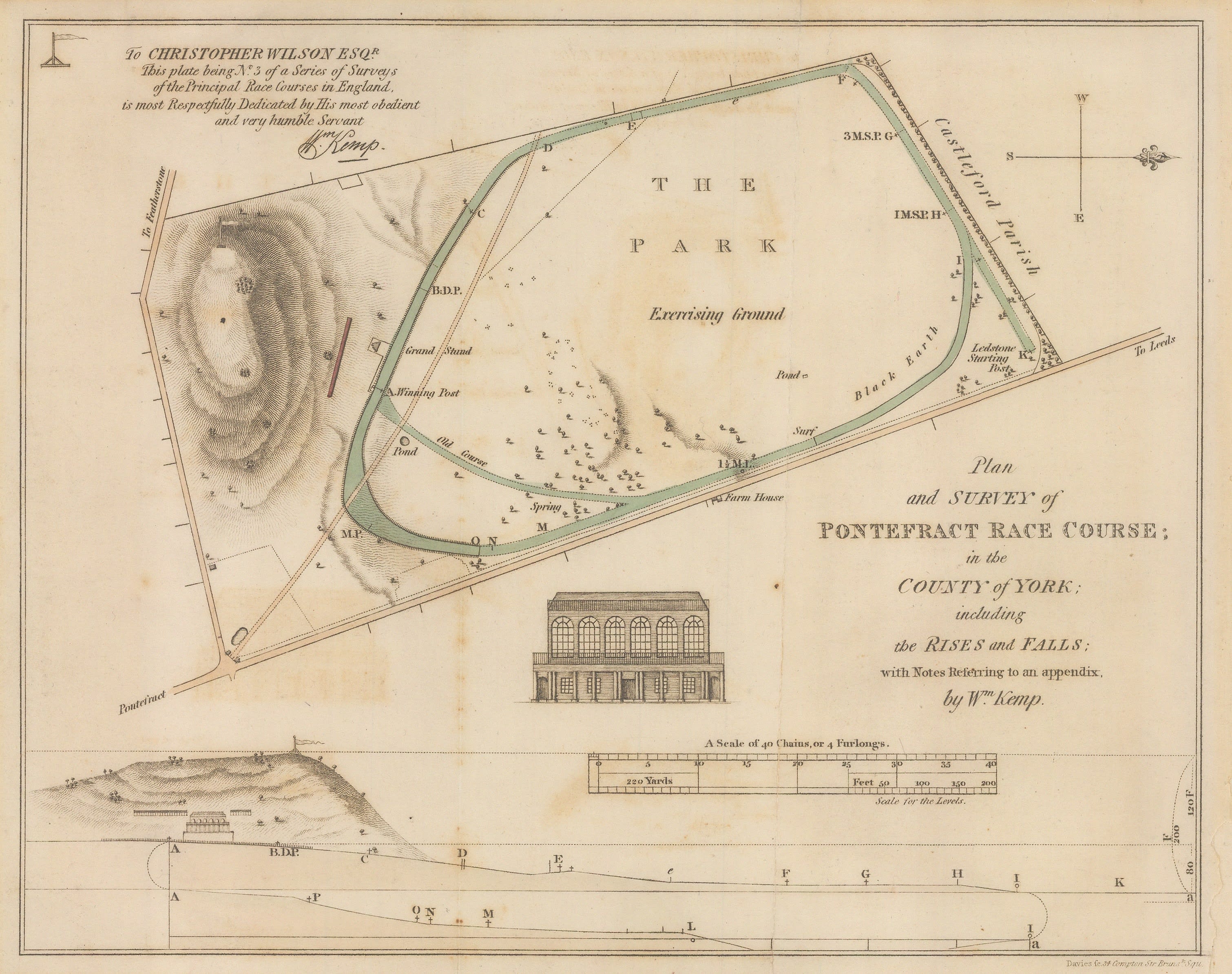

The largest continuous flat racecourse in Europe, races were first held in the meadows of Pontefract in the 17th century, becoming more formal in the 18th, and from the 19th, starting at 14:45 to allow local miners time to make the meets.

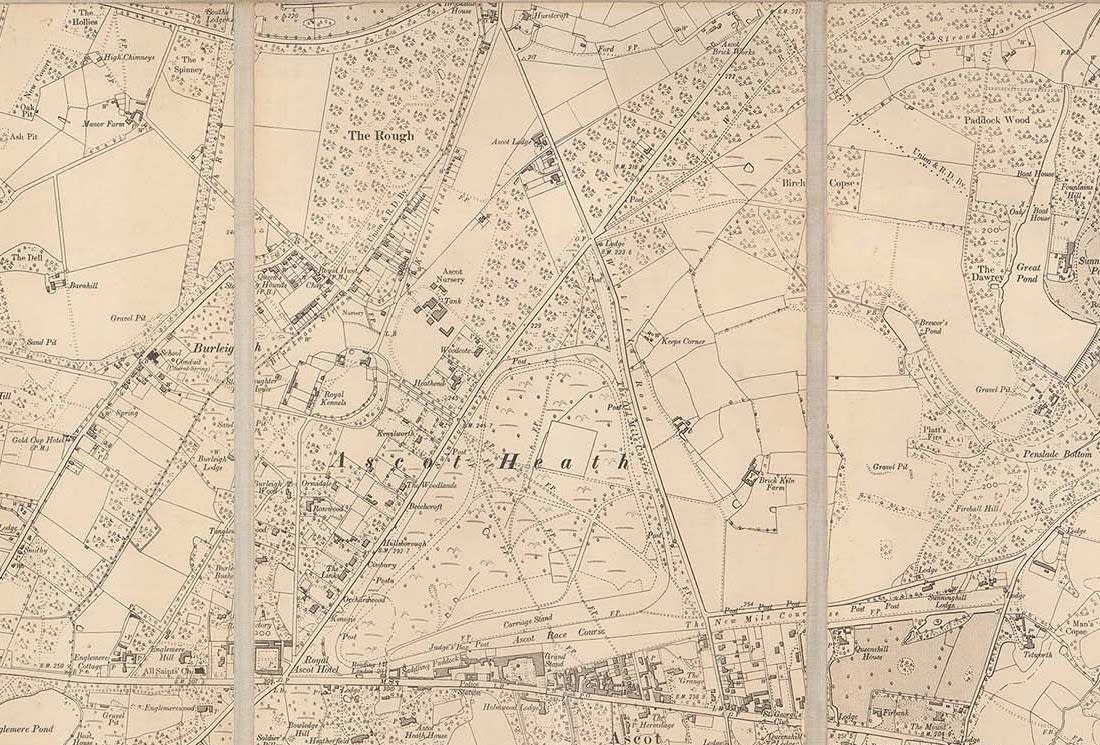

In Queen Anne’s reign racecourses were founded throughout the country including Ascot. Although still relying heavily on the patronage of the upper classes, racing had extended considerably beyond a private event. Racehorse breeding had also developed, and was forever altered by the arrival in England of the great Byerley Turk c1690, Darley Arabian c1720s and Godolphin Arabian c1730s, the first celebrity horses and originators of all modern thoroughbreds.

Founded in 1711 by Queen Anne, Ascot initially only held the four day Royal meeting. This continues today under the patronage of HM The Queen, a keen racing enthusiast.

In 1750 the Jockey Club was formed by a group of gentlemen enthusiasts; its first resolutions were the ‘weighing in’ of riders and that all riders must wear the ‘colour’ of the horse’s owner. It later designated the 5 Classics -the 2000 Guineas, Epsom Derby and St Ledger (Triple Crown) and the 1,000 Guineas and Epsom Oaks (fillies only), and established the General Stud book through which all horses raced and known as thoroughbreds must be traced.

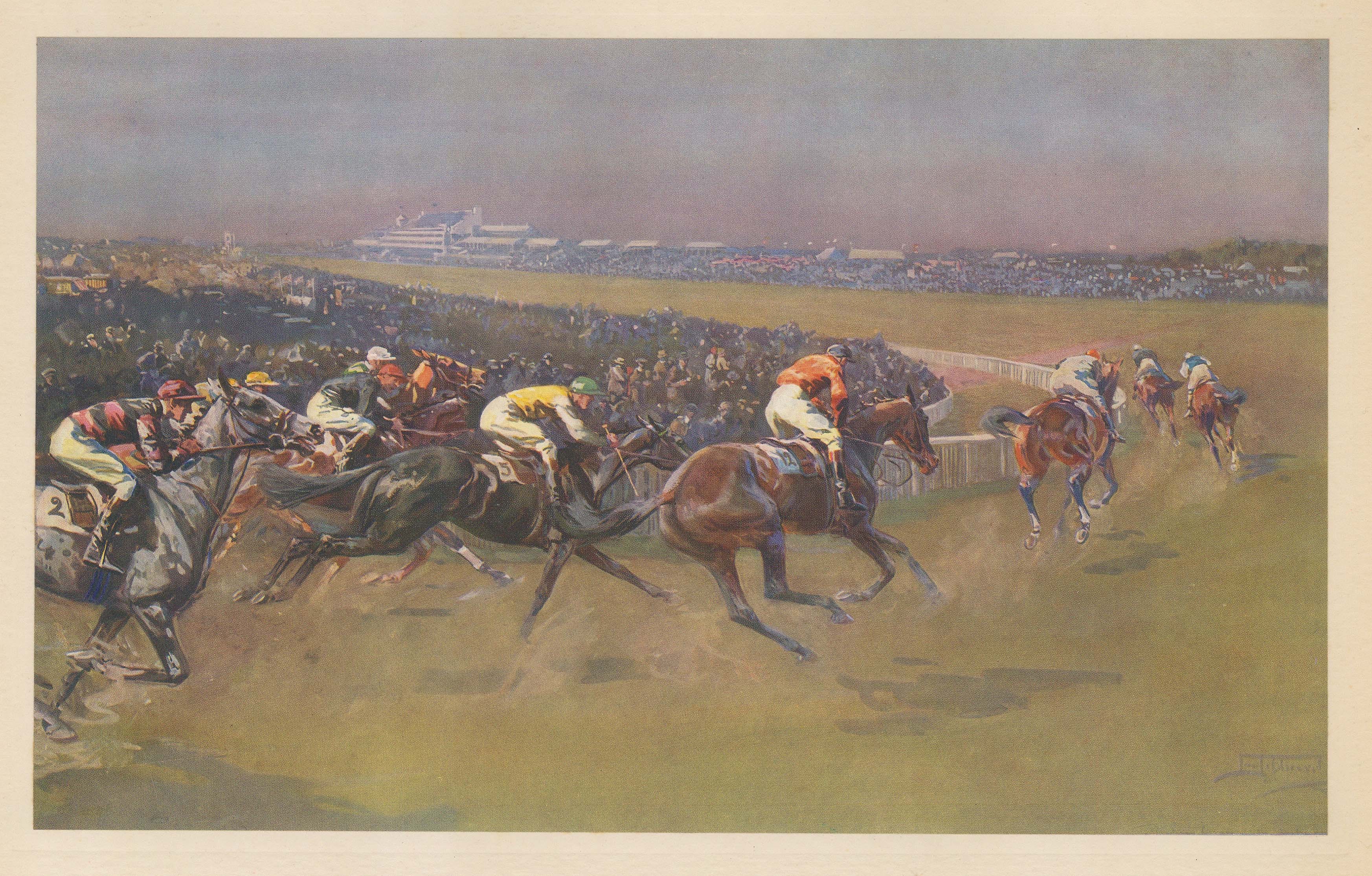

Lionel Edwards: Tattenham Corner, Epsom Derby. 1937. An original vintage chromolithograph. 14" x 9". [SPORTSp3555]. The famous Tattenham Corner added to Epsom to extend the course in 1784. It was here that Emily Davison famously dashed into the 1913 Derby in a bid to draw attention to the suffragettes’ cause. She was struck by King George V’s horse Anmer and died hours later from her injuries.

By the beginning of the 19th century, racing was capturing the interest of the ascending middle classes and urban elite, and by 1839 more than 150 towns held annual races at various times throughout the year. Racing fever grew throughout the century and as with most assembling of crowds in Victorian England more often than not descended into disorder. Regardless of the notoriety of the sport for its fixed meets, welshing bookies and thieves in the crowd, all levels of society would eagerly flock to courses in the hopes of winning fortunes or at the very least see their favoured horses and jockeys.

Herring Jack Robinson on Cadland. 1828. A original colour antique aquatint. 18" x 14". [SPORTSp3288]

With a riding career of nearly 50 years, James ‘Jem’ Robinson rode the winners of 24 British Classic Races. His six Derby wins were not exceeded until Lester Piggott in 1976 whilst his nine 2000 Guineas wins remains unsurpassed.

Although steeplechases continued to be ridden mostly by ‘gentleman jockeys’, flat racing had evolved well away from its patrician roots. Jockeys, once little more than servants, were now elevated to nationally recognised figures. The first of the ‘sport celebrities’, they even found a place in the society magazine, Vanity Fair, amongst Royalty, Prime Ministers and other leading figures of the day. Dynasties of racing families were common with complex webs of jockeys, trainers and breeders. Although they were indeed the pop stars of their day, the constraints of Victorian society had yet to unravel in the Great War, and few jockeys were involved in the development of the sport which was largely left to owners and enthusiasts.

Vanity Fair: Tattersall's, Newmarket. 1887. An original antique chromolithograph. 21" x 15". [SPORTSp3588]

Since 1766 Tattersall’s has attracted the most influential names in racing to its auctions. In 1887 Liberio Prosperi created this caricature of the Prince of Wales, Prince Saltykoff, the Duke of Beaufort, the Duke of Hamilton, the Duke of Westminster, Lord Falmouth, Lord Zetland, Lord Cadogan, and other racing grandees.

In 1888 Liborio Prosperi, an Italian caricaturist who specialised in racing, drew his fantasy race for Vanity Fair with eight of that year’s most successful jockeys. He also included two notable figures – John Francis Clark, racing judge and architect of grandstands, notably at Chelmsford, and one of the greatest patrons of the turf, Sir John Astley. Astley, a decorated officer of the Scots Guards, was a pillar of Newmarket’s community during the second half of the 19th century, and ironically given the nickname ‘The Mate’ as he was perceived to possess a nautical air. He was elected to the Jockey Club and established the Astley Institute, a social club for stablemen which exists today.

Vanity Fair:The Winning Post. 1888. An original antique chromolihograph. 21" x 15". [SPORTSp3589]

The Winning Post. Liberio Prosperi for Vanity Fair, 1888.

Jockeys from Left to Right:

John Osborne was a highly popular and very successful jockey riding for nearly 46 years. In 1888 at the age of 55 he won the 2,000. Father to 13, he was awarded £3,600 guineas on his retirement from a nationwide testimonial fund, a vast sum at the time.

Tom Cannon was Champion Jockey in flat racing who crossed over to the jumps, winning the Grand National in 1888. He went on to be a trainer and tutor to numerous successful jockeys. He was father to the six times Champion Jockey Morny Cannon and great grandfather to Lester Piggott, and unusually ended his days at the venerable age of 72.

Jack Watts rode his first winner at the age of 15 in 1880. He continually battled with his weight and never attained the prize of Champion Jockey although he did make runner up in 1891. He retired in 1900 and died 2 years later from a lifetime of ‘wasting’.

Frederic Webb was a Champion Jockey who went on to train for numerous well known owners at Newmarket including Lillie Langtry and Lord Shrewsbury, and later was employed as trainer for Prince Thurn und Taxis in Hungary.

Fred Barrett was a jockey known more for his failures than his victories with a reputation for erratic riding. However in 1888 he was the Champion Jockey with 108 wins, just narrowly beating his brother George. He went on to be a trainer but died at 27, again from a lifetime of ‘wasting’.

George Barrett had ridden 3 winners at Newmarket by the age of 15 and although always pipped to the post for Champion Jockey, from 1879-1894 he rode over 1,400 horses to win, with another nearly 2,500 coming 2nd and 3rd. A savvy investor amassing a considerable fortune, he too died from a lifetime of ‘wasting’ at 35.

William ‘Jack’ Robinson, jockey turned trainer, is best remembered for his part in the Craganour affair. Passing the post first in the 2000 Guineas, one judge declared the 2nd placed horse the winner. Craganour’s owner was the unpopular Charles Bower Ismay whose family’s White Star line’s flagship Titanic had sunk the year before, and whose brother, having survived, was known as the ‘coward of the Titanic’. At the 1913 Derby, the very same where suffragette Emily Davison was killed, Craganour won again only to be disqualified. Robinson was said to be left broken by the affair and died not long after.

Fred Rickaby was described as the soundest and most hard-working jockey of his generation. His father was a trainer and his son Frederick Lester was following in his footsteps with a growing list of wins before enlisting in the Veterinary Corp in 1916. Frederick Lester died in the final days of the war at 23 and his younger sister named her son after him. Lester Piggott went on to be one of the greatest jockeys of the 20th century with wins alone of 4, 493.

Written by S. A. Obolensky, 2018

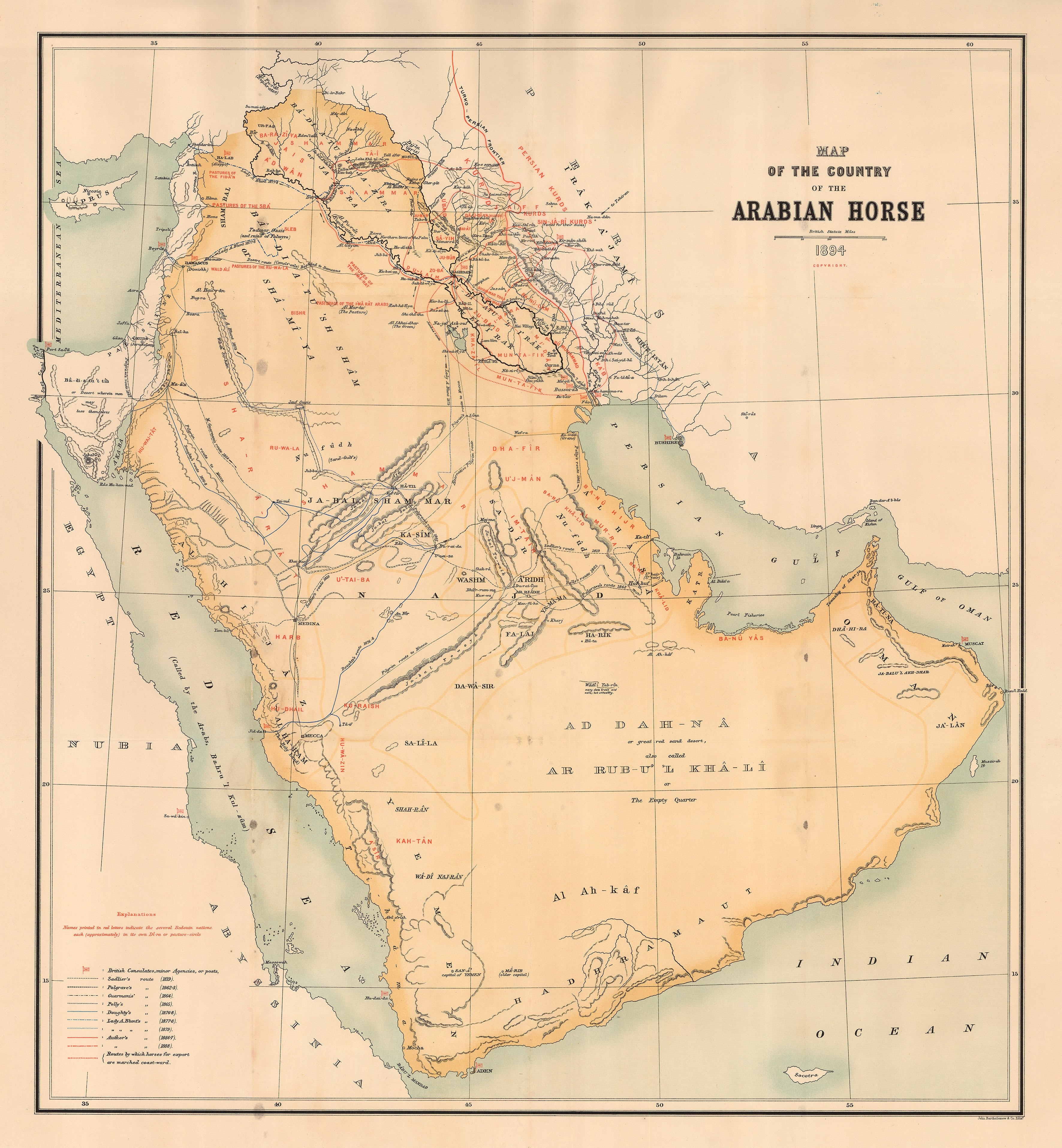

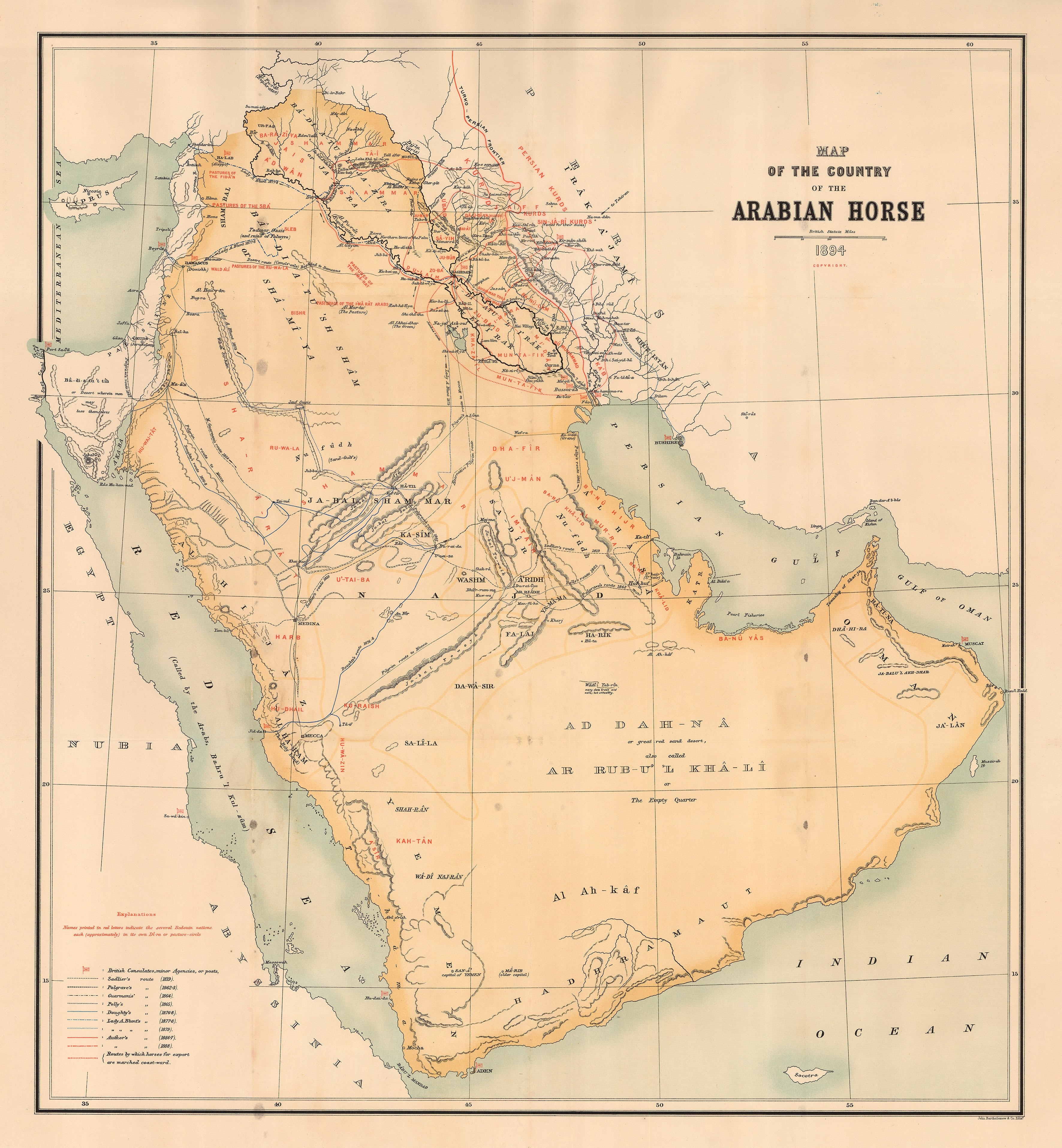

Since the 12th century when knights returned from the Crusades with Arab horses, the Arabian horse has been integral to race horse breeding in Britain. Maj General William Tweedie – diplomat, soldier and ardent enthusiast of Arabia- issued his definitive work on the Arabian horse in 1894.

Since the 12th century when knights returned from the Crusades with Arab horses, the Arabian horse has been integral to race horse breeding in Britain. Maj General William Tweedie – diplomat, soldier and ardent enthusiast of Arabia- issued his definitive work on the Arabian horse in 1894.

About the author

The Map House