This International Women’s Day, we are celebrating a remarkable woman – pioneer of investigative journalism in America, rights activist and intrepid traveller, Elizabeth Jane Cochran (1864-1922), better known as Nellie Bly.

Portrait of Elizabeth Jane Cochran. Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress Archive.

Portrait of Elizabeth Jane Cochran. Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress Archive.

She was born in 1864 in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania to a large working class family. In 1880, after her mother had finalised divorce proceedings with her abusive alcoholic step-father, the family moved to Pittsburgh in search of a better life.

Upon reading a column in the local newspaper, the Pittsburgh Dispatch titled “What Girls Are Good For” about the talents of women being limited to motherhood and housework, she sent an angry rebuttal penned under pseudonym “Lonely Orphan Girl”.

Her impassioned writing skills impressed the editor, George Madden, who put out an advertisement asking her to make herself known. When she did so she was offered a trial position, thus began her career in journalism.

An article about divorce from a woman’s perspective calling for reform of divorce laws citing her mother’s traumatic experience. George Madden again impressed by her passion, offered her a permanent job under her new pen name, Nellie Bly.

Bly’s signature. Image courtesy of Penn University Library.

She used her position to voice concerns about systematic and political corruption, human rights and writing articles focusing on the lives of working women. These controversial topics caused a stir and some companies stopped advertising in the Dispatch. Bly was reduced to contributing to the “Women’s Pages”, on such anodyne subjects as fashion, society and the arts.

Frustrated, Bly set about on a new adventure and moved to New York in 1887 at just 23. She blagged her way into the office of Joseph Pulitzer at The New York World newspaper, where she started work as a reporter.

There were rumours of truly horrific conditions, brutality and neglect at Blackwell Island Women’s Lunatic Asylum. Bly, feigning mental illness had herself incarcerated. Her reports from inside the asylum were devastating, and her findings spurred on reforms, better care and better funding within mental hospitals.

Following her articles and the success of her book, “Ten Days in a Mad-House” (1887), she received approval on her ambitious project to match Jules Verne’s fictitious hero Phileas Fogg’s travels in “Around the World in 80 Days” (1873).

Bly in Bly her exploring attire. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

It had taken a whole year to convince Joseph Pulitzer to let her undertake the challenge, with him even stating that “no-one but a man could do this”. Refusing to let her gender did not stunt her ability and that she was perfectly capable of travelling on her own. Bly departed on 14th November 1889 from from Hoboken, New Jersey aboard the steamship “Augusta Victoria” wearing a sturdy overcoat, a single Gladstone bag and with a purse containing a few hundred dollars tied around her neck.

Travelling across the Atlantic and enduring awful seasickness, she reached London seven days into her trip and Paris shortly after, taking a slight detour to meet with author Jules Verne in Amiens. She pressed on through Europe, across the Mediterranean to Egypt, through the Suez Canal into the Indian Ocean to Sri Lanka.

Bacon’s 1890 map of the world marked to show route.

Reaching South East Asia, she sailed through the Malacca Straits to Singapore and Borneo. Arriving in Hong Kong on Christmas Day 1889, she was informed that another reporter, Elizabeth Bisland of Cosmopolitan Magazine, had set about racing her around the world in the opposite direction. From Hong Kong, she went on to China and Japan.

Bly was able to make use of the expansive international submarine cable network and send telegram reports of her progress from a number of locations. The stories of her journey published in the newspaper captured the nation’s attention, inspiring a “Nellie Bly Guessing Match”. A generous prize of a trip to Europe meant that thousands of people attempted to guess her arrival time.

Rough weather across the Pacific on her journey from Asia to the west coast of America set her back. On her arrival into San Francisco, Pulitzer chartered a private train with a carriage to bring her home to New York in the hope she would make up some of the time lost at sea.

Bly return to New York from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News, 8th Feb 1890. Image courtesy of The Library of Congress.

On 25th January 1890, she returned in triumph 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes and 14 seconds after her departure. Elizabeth Bisland arrived just four and a half days later.

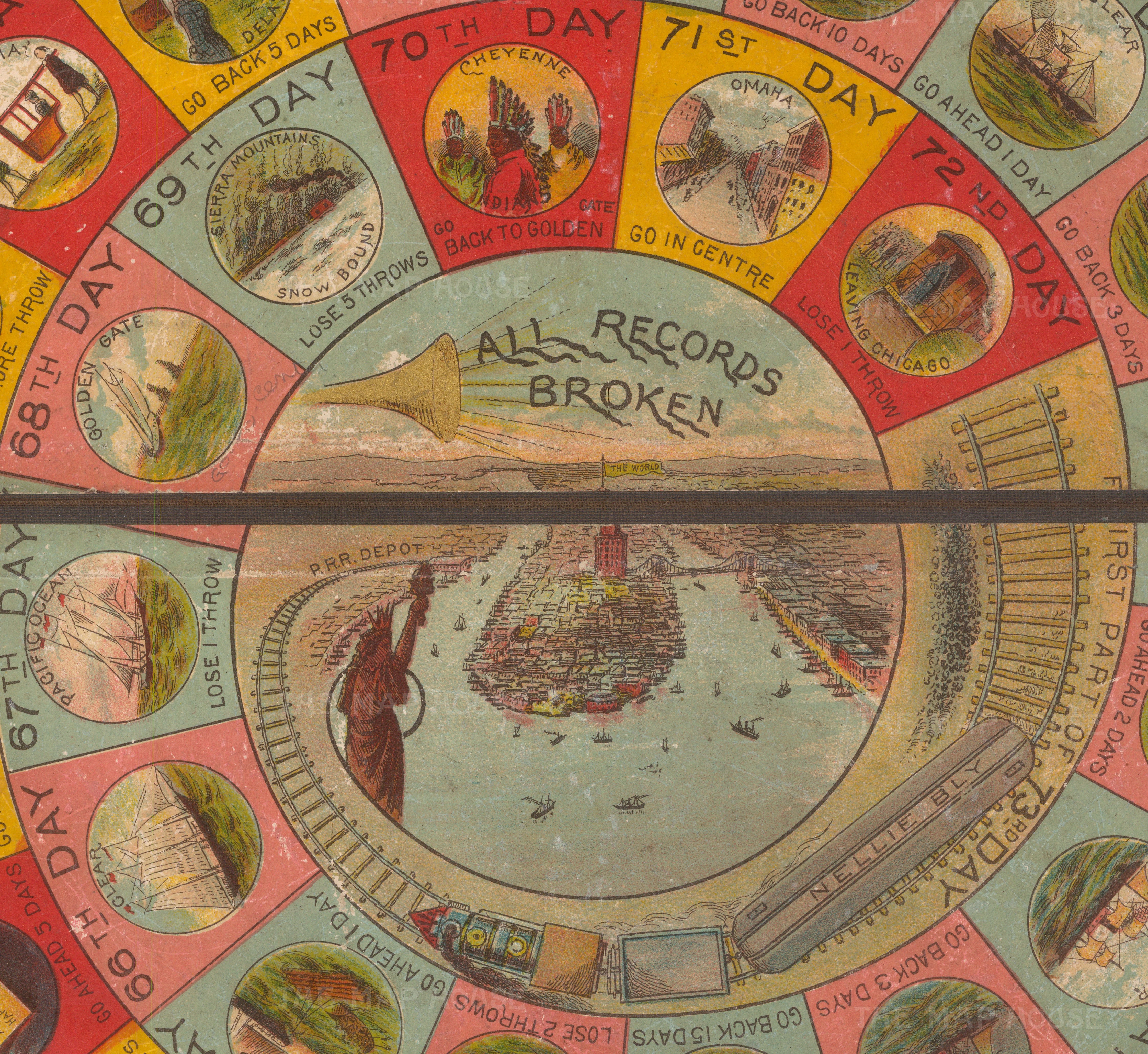

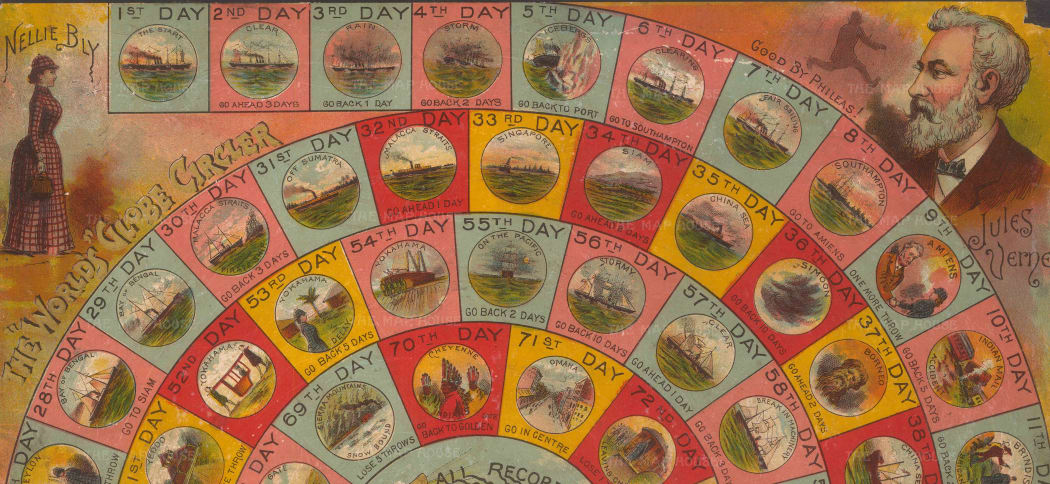

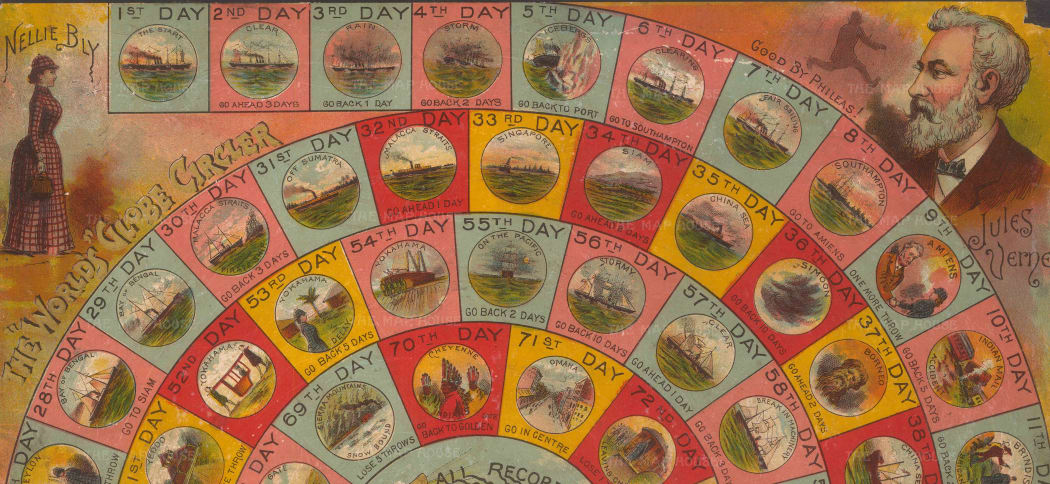

“Round the World with Nellie Bly” board game

This striking board game was produced by New York publishers, McLoughlin Brothers, to celebrate and allow players to emulate her record breaking achievement. We are fortunate enough to have an example in The Map House collection.

Nellie Bly’s efforts to speak out for those without a voice, to turn gender prejudice on its head, and her landmark actions in the early days of investigative journalism have seen her gain a well-earned place in history. Whilst stories of solo female adventure around the globe are now commonplace, they owe so much to Bly, Bisland and other women pioneers who paved the way.

“I said I could and I would. And I did”.

© Mary Alice Beal, 2019

About the author

The Map House

Bly in Bly her exploring attire. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Bly in Bly her exploring attire. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.