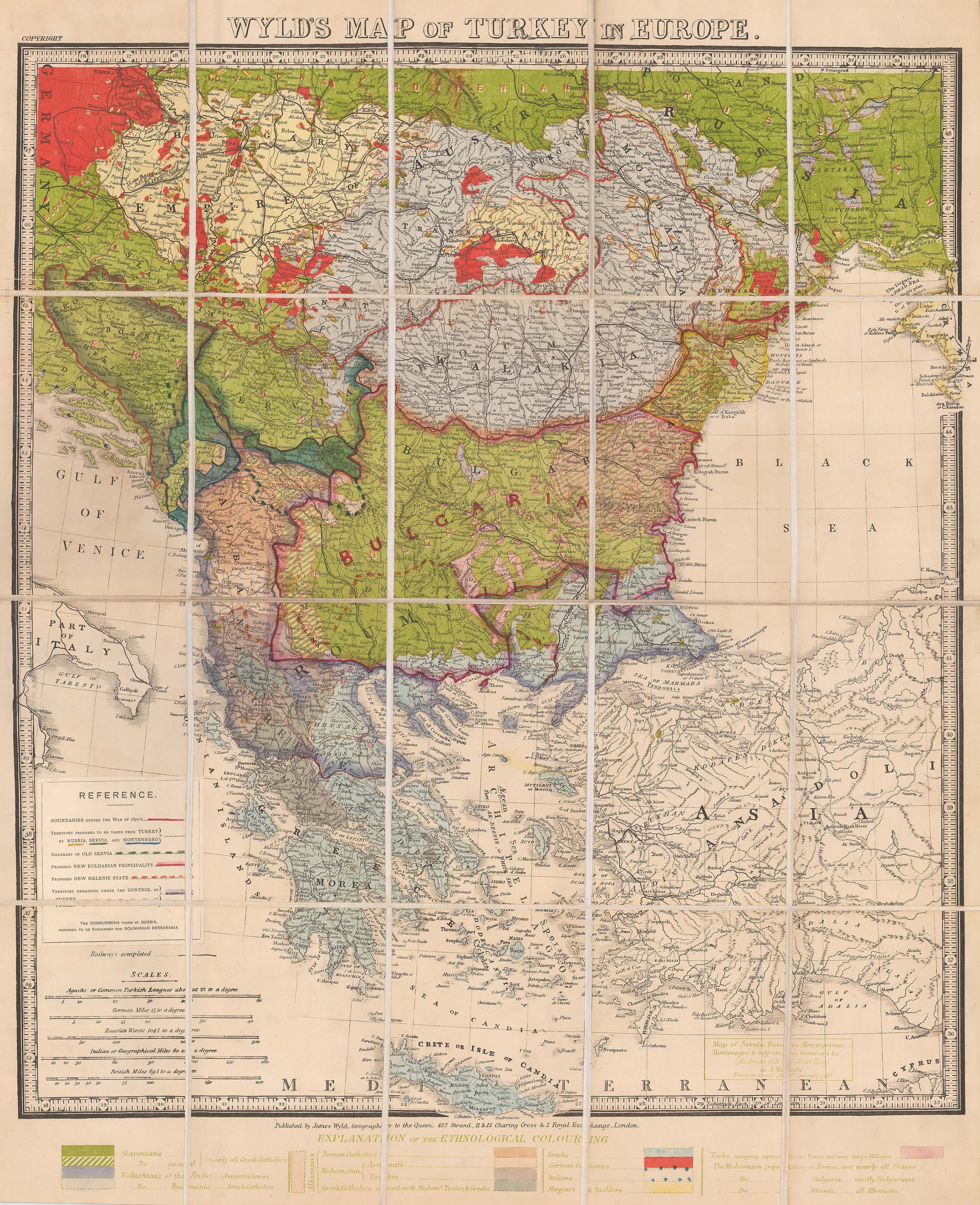

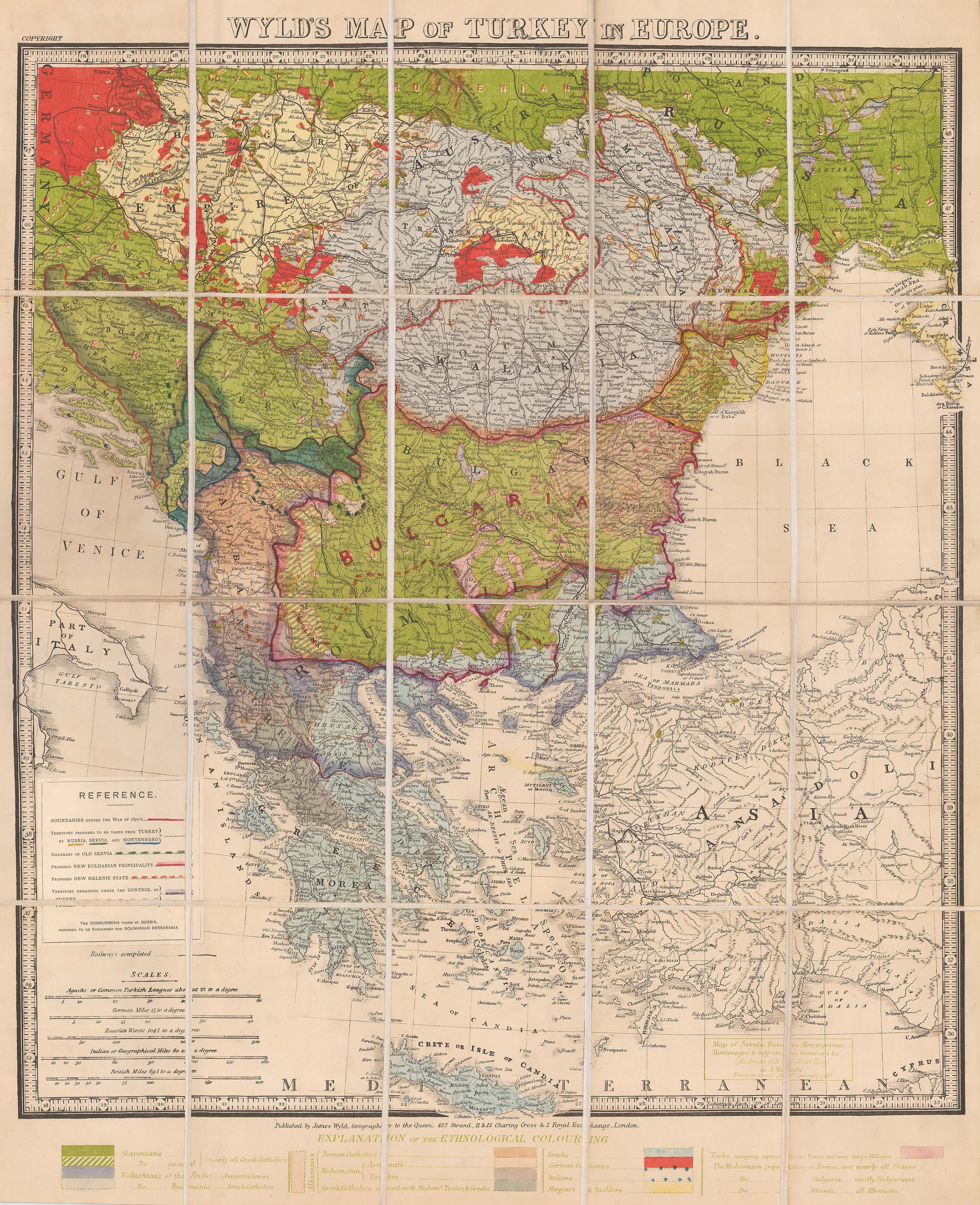

The map featured on our blog today is a very complicated piece of cartography. It was first issued as a topographical folding map of the Balkan Peninsula; however, in 1878, the publisher James Wyld altered it dramatically to illustrate and explain the claims, counter claims and diplomatic maneuverings of the Great Eastern Crisis which led to the pivotal Congress of Berlin of 1878.

This was a commercially opportunistic piece of mapmaking, typical of that great entrepreneur, James Wyld. He specialized in seizing upon important political events or questions of the day and rushing out maps which explained the “Question” or issue through the medium of cartography. Due to their ephemeral nature and their short lived appeal, these zeitgeist political maps are extremely rare and we have not been able to track down another example of this particular one in an institution.

The background to the Treaty of Berlin is convoluted but ultimately, it stems from the struggle for independence by Balkan States such as Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro from the Ottoman Empire. Simultaneously, it reflects the concerns of the great European powers of the day regarding the growing military might and territorial ambitions of Russia.

The Ottomans had been engaged in a long series of conflicts with Russia throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These had sapped their strength and economy. Arguably, the most serious of these was the Crimean War (1853-6). For the first time, the Empire had to borrow money from European banks initially to pay for the war, but by 1875 this external debt had risen to two hundred million pounds. (That equates to approximately ninety two billion pounds today). Some of this was due to infrastructure spending, such as railways and the military; another proportion went on the building and maintenance of the Ottoman Navy, which was the third largest in the world at this point, with 21 battleships; and finally, the Imperial Court was infamous for its lavish lifestyle. The unsustainability of this debt was brought to a head by a series of natural disasters, notably drought in 1873 and flooding in 1874, both of which were followed by famine. Ultimately, this caused the Empire to default on its debt in 1875.

The default necessitated a rise in taxes. There was already great discontent in the Balkan provinces over continued Ottoman domination and this tax rise acted as tinder to a spark. A series of revolts and armed uprisings erupted in Bulgaria, Herzegovina and Serbia. The Ottoman army was sent into the rebel provinces and more importantly, local Islamic militia was recruited to help deal with the Christian section of the population. There was a spate of atrocities throughout the region, mostly instigated by the militia,which brought widespread condemnation from both European powers and the United States. In particular, Russia felt that the treatment of Christians in Bulgaria was beyond the pale. Russian volunteers featured prominently in the Serbian uprising but that had not gone well and Serbia asked for help from the Great Powers of the time. There was an attempt at mediation in Constantinople but the Ottoman Empire was not invited, infuriating the Sultan and leading the Empire to discredit this peace making attempt. Ironically this was called the Constantinople Conference.

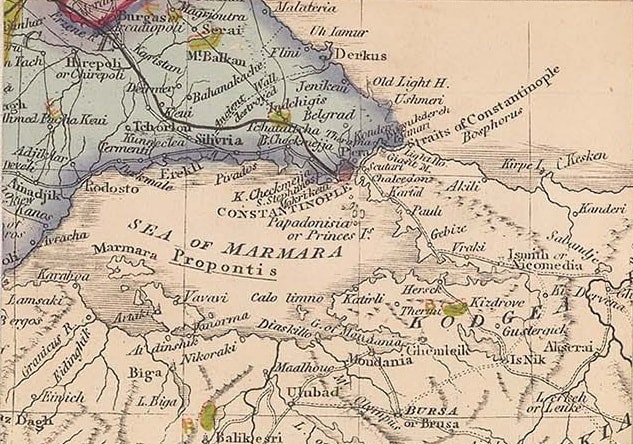

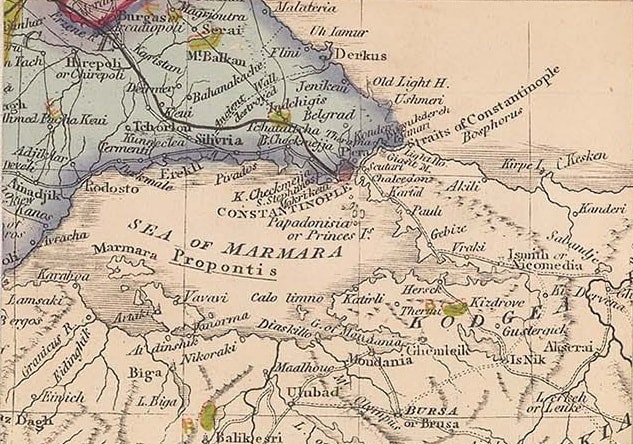

Not deterred by their setbacks in Serbia and determined to halt the massacres, Russian forces crossed into Romania in 1877, thus precipitating another Russo-Turkish War. Despite some early successes, the war was a disaster for the Ottoman forces. It was fought on two fronts: the Balkans and the Caucasus. The Russians crossed the Danube and by early 1878, were marching towards Constantinople, often supported by the local population. They reached the village of San Stefano, approximately seven miles west of Constantinople. The Russians only stopped due to the presence of a British fleet in the Sea of Marmara, which had warned them to stay outside the city. In the Caucasus, the situation was just as bad; a Russian army, outnumbered two to one, captured large areas of land on the Turko-Russian border, which ultimately became the Kars Oblast.

The war ended by the signing of the Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano, named after the aforementioned village. In brief, this treaty ensured the following: Bulgaria became a Principality and nominally independent although to all intents and purposes it was sponsored and occupied by Russian forces, who were to stay for at least two years to ensure its security. It was to be given a vast new area of land, including Macedonia and large parts of Thrace. All Ottoman forces had to withdraw.

Montenegro, Serbia and Romania became independent and all of them gained formerly Ottoman lands.

Bosnia Herzegovina was to become independent and Crete and Thessaly were to get a limited form of autonomy. Finally, both the Straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus were to become neutral and open to all shipping. Although Russia attempted to slip this in, it would have allowed Russian fleets access to the Mediterranean and as far as the British were concerned, this was a very dangerous development.

In the Caucasus, the Russian forces consolidated their gains, stating that the local population perceived them as liberators rather than conquerors.

The terms of this Treaty created an uproar and led to the hastily convened Congress of Berlin in October 1878; the main agenda was the Treaty of Berlin. The attendees read like a list of 19th century political greats: Bismarck, Von Bulow, Disraeli, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, Ali Pasha and Alexander, Prince Gochakov, among various other representatives.

By this point the main aim of Prussia, France, Italy, Austria Hungary and Great Britain was to curtail Russian advances in the Balkans and potentially into the Mediterranean. The vast, newly created Principality of Bulgaria had also sown a great deal of disquiet among the rest of the Balkan states, especially Serbia.

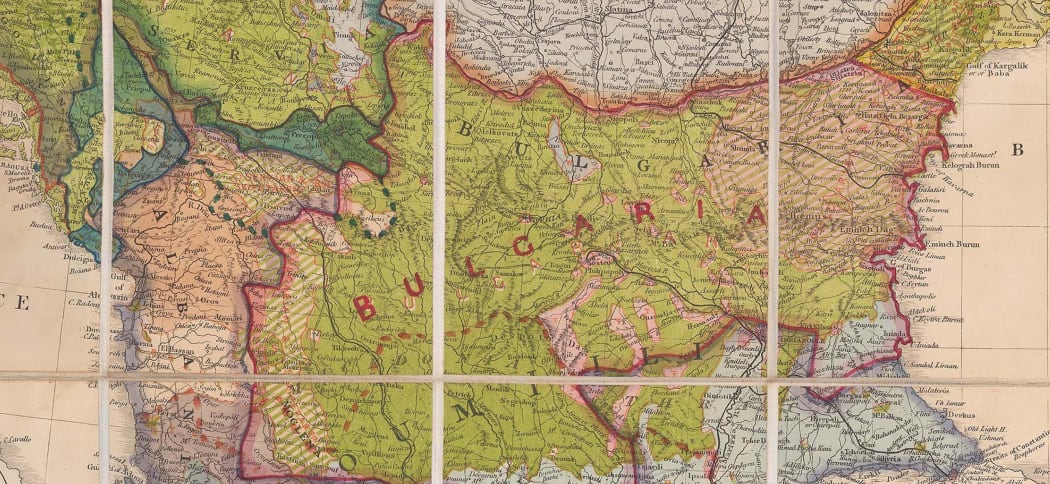

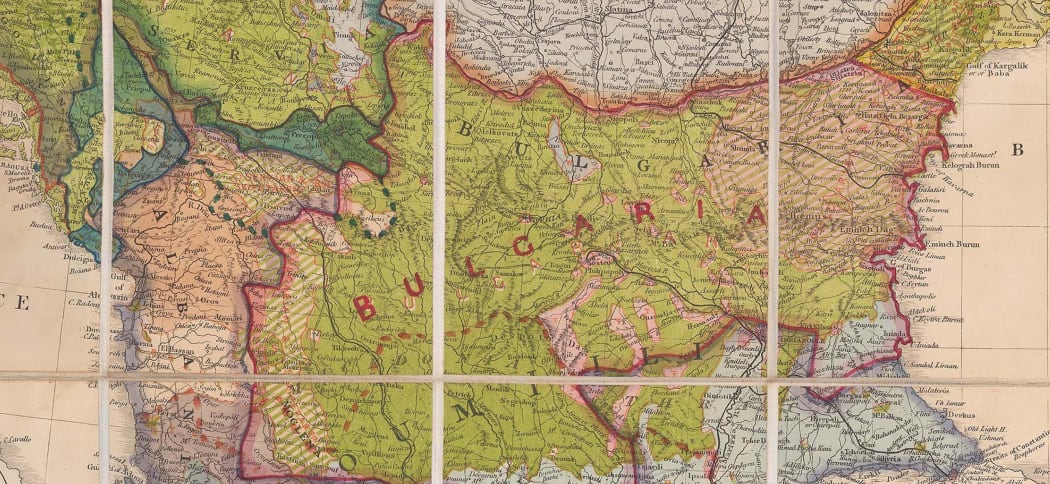

As our map illustrates, after the Treaty of San Stefano, the Balkans are now dominated by a huge region named Bulgaria and the regions of Walachia, Transylvania and Moldavia.

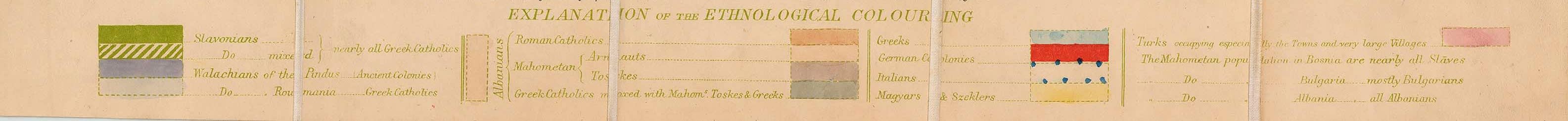

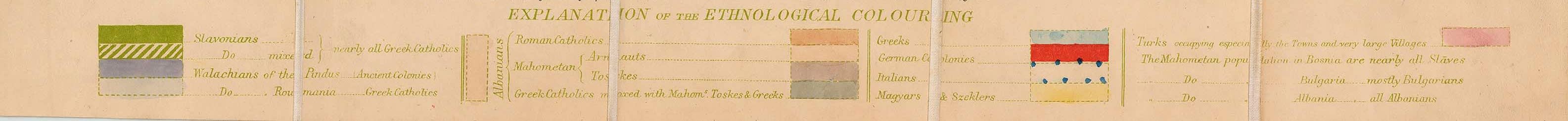

Wyld helpfully provides a colour coded key added to the lower margin which attempts to show the complicated ethnology of the region. Among other curiosities, it records the “Saxony villages” or enclaves of German speaking regions in Hungary and Transylvania; these he terms as “German Colonies”. He attempts to explain the complicated mix of religions in Albania, including Greek Orthodox, Catholics and Muslims; he also states in a rather sinister way that the Muslim population of Bosnia are nearly all slaves and that the Muslim population of Bulgaria are ethnic Bulgarians and the same with Albanians. The colour of the map also clearly denotes the extent of the Austro Hungarian Empire and its claims, and the buffer zone of Bessarabia between the Ottomans and the Russians.

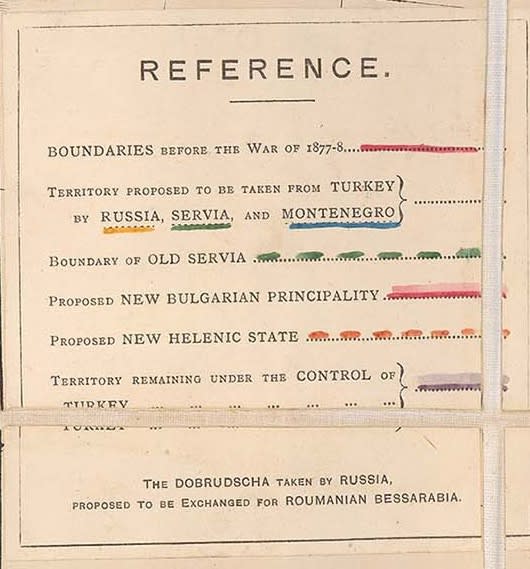

On the lower left of the map is a pasted explanation of previous borders and claims. These include a Greek claims to move its Northern border and make substantial land gains, the territorial claims of Russia, Serbia and Montenegro, the newly proposed borders of Bulgaria and a very small area near Constantinople to be left under the control of the Ottoman Empire.

referenceThe results of the Congress were ultimately a compromise. The region of Greater Bulgaria as it became known, was partitioned and the Ottomans regained Macedonia, effectively blocking Russian influence to the Sea of Marmara. Montenegro, Serbia, Eastern Roumelia and Bulgaria became, to all intents and purposes, independent states, which quickly declared themselves kingdoms. It also sparked the beginning of negotiations between the Ottoman Empire and Greece which ultimately resulted in the handover of Thessaly to the latter although this did not happen until 1881.

A curious note on the lower part of the panel refers to the Dobrudscha taken by Russia to be exchanged for Bessarabia. This is a reference to the Dobrujan Germans, another curious group which settled in modern Bulgaria and Bessarabia. Although ethnically German, they were technically Turkish subjects and had been captured during the Russian advance of 1877. It was this group that was used by the Russians as a successful lever to gain Bessarabia. Prussian influence on the Ottoman Empire was very strong.

The Russian clause for neutrality for all shipping through the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus was never acknowledged. The London Straits Convention remained as the binding Treaty, forbidding any warships bar those of the Sultan and his allies from using these Straits.

Tucked away in minor parts of the Treaty were several clauses which were to have fateful consequences. Britain was given the island of Cyprus, probably to develop as a naval base to support the Turkish fleet in case the Russian Black Sea fleet attempted a forced exit through the Straits. Austria-Hungary was given the right to occupy the Turkish Vilayet of Bosnia. This was a peculiar position as technically, Bosnia was still Turkish but it was administered both in civil matters and militarily by Austria-Hungary.

The Austrians decided to annex Bosnia completely in 1908. This led to the Bosnian Crisis and fanned the flames of nationalism among the Bosnian Serbs. On the 28th of June 1914, in Serajevo, a fanatical Serb nationalist, Gavrilo Princip shot and killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne. This infamous deed was a direct catalyst to the start of the Great War.

To see this map on our website, click here. And if you would like more information about this map contact us at maps@themaphouse.com and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram for map musings and exciting announcements.

About the author

The Map House