This Map of the Month is a piece celebrated as one of the most important documents in the annals of European activity in the Far East.

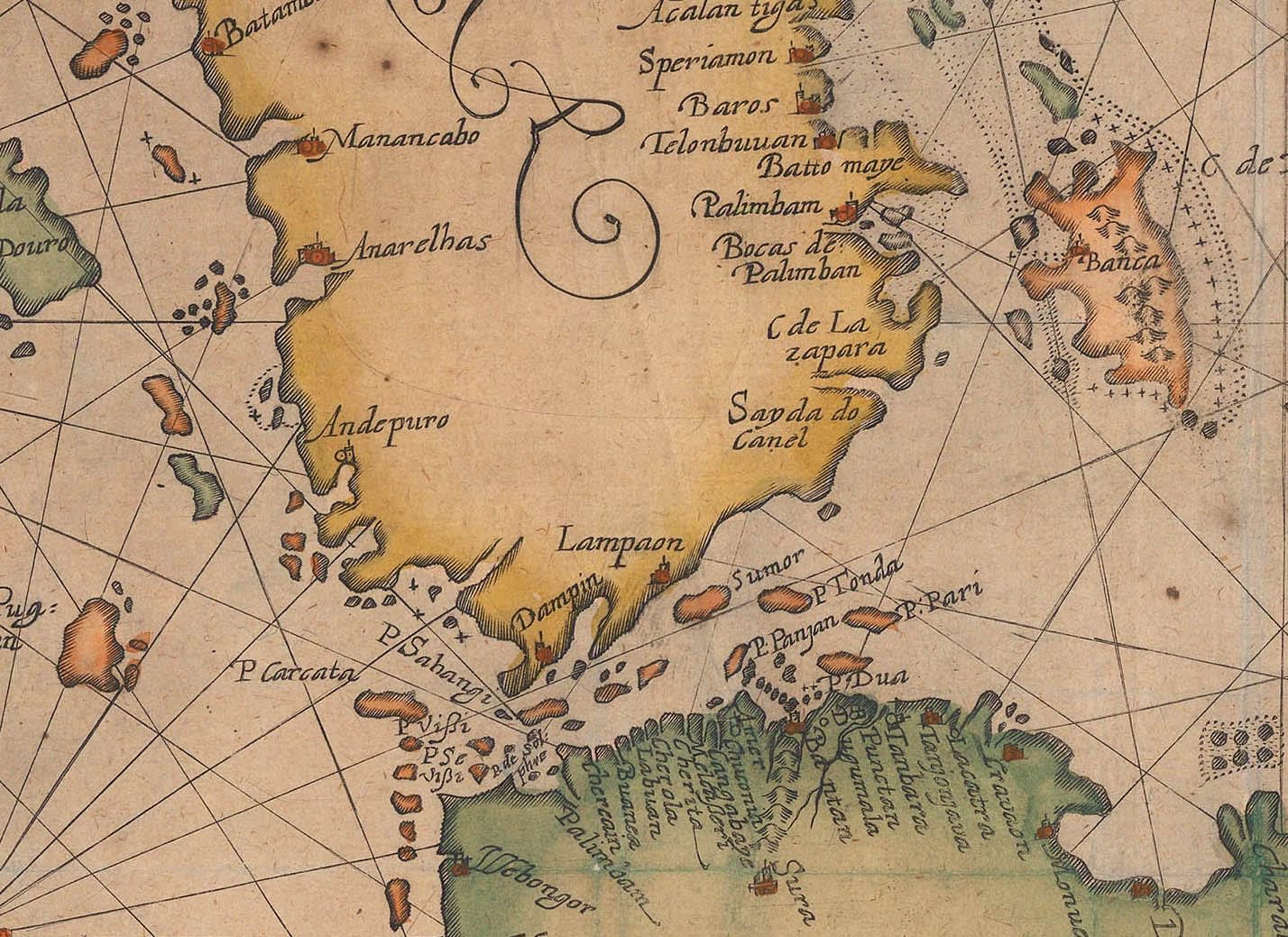

The “Nova Tabula Insularum Iavae, Sumatrae, Borneonis et aliarum Mallacam” was issued in 1598 by Theodor de Bry and it is the first commercially available map to focus on the strategically important region of the Western Java Sea, the islands of Java, Sumatra and the South coast of Borneo as well as Southern Malaya; it also includes the Straits of Sunda, Malacca and Singapore. It is a foundation document for the activities of the Dutch in this region, activities which ultimately led to the establishment of the Dutch East India Company in 1602 and the later conversion of the Company’s holdings into the Dutch East Indies in 1800, an overseas possession which Holland held until World War II.

In the late 16th century, early attempts by the Dutch to vie with the Portuguese and the Spanish for Asian trade are full of stories of spies, intrigue and deeds of derring-do; but for the purposes of this article, two key individuals stand out: Jan Huyghen van Linschoten and Cornelis de Houtman.

Although Linschoten’s achievements deserve a completely separate post, in this instance he plays a small but important part in the creation of this map. Linschoten had been a secretary to the Portuguese Bishop of Goa and whilst there, he managed to gain access to important Portuguese marine documents including charts and accounts of trading activities in both India and the Far East. After a truly epic journey back to Holland which included a stint in a Portuguese dungeon in Goa and a shipwreck on the Azores, Linschoten published an account of his adventures which caused a sensation and became an instant bestseller.

The orthodox route to the East Indies at the time was to sail around the Cape of Good Hope and navigate along the East coast of Africa, turn East past Arabia and the coast of Beluchistan before reaching India; once there, a ship would follow the coast of the sub-continent, leading to the coast of Bengal, continuing along the coasts of Burma and Malaya which ultimately became the Straits of Malacca and Singapore. Crucially, Linschoten had learned of an alternate route which involved sailing East from the Cape, through the Indian Ocean leading to an alternate Strait, between the south coast of Sumatra and the North coast of Java, namely the Sunda Straits. In terms of navigation, it was a riskier route as it involved more sailing on the open seas and less opportunity to use landmarks along the coasts but the Straits of Malacca and Singapore were controlled by the Portuguese, who fiercely protected their monopoly on Asian trade.

Linschoten communicated this information about the new route to interested parties and in 1595, two merchants sponsored a speculative voyage using Linschoten’s information. To head this enterprise, they chose Cornelis de Houtman, another Dutch agent, who had lived in Lisbon and also gained access to Portuguese sailing methods, charts and mercantile accounts.

Taking the voyage as a single enterprise, the best way to describe it would be difficult. Financially, it barely broke even; one ship out of the fleet of four, was lost in strange circumstances, when it was deliberately burnt and one of the ship’s captains died mysteriously, supposedly poisoned by de Houtman. De Houtman himself also seems to have been a difficult individual with several descriptions detailing episodes of his rudeness and his inability to establish diplomatic relations with local rulers. Ultimately, the remaining three ships returned to Holland with a small cargo of pepper in August of 1597. Out of a crew of 249, only 87 returned. The casualties were caused mainly by a combination of disease and piracy.

However, taken in a historical context, this voyage changed European history. Most importantly, it established that there was a viable marine route through the Sunda Straits, thus breaking the Portuguese monopoly in the region. De Houten, despite his diplomatic shortcomings, did manage to establish a commercial factory in the thriving city of Bantem, an important pepper trading port. This was the first Dutch factory in the East Indies and became the foundation for the establishment of the Dutch East India Company. Finally, it also indicated that the Portuguese presence in the region was not as strong as previously thought, encouraging more activity not only by the Dutch but also by the English and the French.

As with Linschoten’s epic return, the voyage caused a sensation and the population of Holland was clamouring for information about this extraordinary enterprise. Within less than a year, an anonymous account of the voyage had been published by Barent Langenes. A further, more substantial work was published in April of 1598 by Cornelis Claesz and it is in this work that a reference to a general map of the region is first made. The account is based on the manuscript of one of the members of the expedition, Willem Lodewijksz. A note in the account mentions a new general map which was supposed to have been included within the work but the map is absent. It must have been done at the last moments but the merchants who had an interest in the expedition forbade the publisher to use Lodewijksz’s map, fearful of disseminating secrets about the discoveries made by the voyage.

Although the merchants were able to suppress the use of this map in the “Historie van Indien”, it was published as a separate sheet in 1598, available for sale to the general public. As a loose piece of paper, its life was very limited and today, there are very few surviving examples only existing in institutions; but at the time, one example was purchased by Theodor de Bry, the foremost German publisher of the period. He was engaged in producing chronicles of the great voyages of discovery to the New World and the Far East. Of course he recognised the importance of this map and, not being subject to the influence of the merchants of Amsterdam, he engraved his version of Lodewijksz’s map and included it in Part II of his “Petits Voyages” to accompany an account of Linschoten’s adventures. It is this German version that is available today.

The map is drawn in the style of a chart, with rhumb lines and mostly coastal detail. There is a large vignette in the centre, showing four Dutch ships on the Java Sea, obviously a reference to de Houten’s fleet. As was usual for de Bry, the engraving is masterful and it is a beautiful as well as important scientific document.

The title of the map is in Latin and Dutch and states that it is a new map showing the islands of Java, Sumatra, Borneo and the Malaccas. The cartouche also bears the initials G.M.A.L, which stand for Guilielmus M.A. Lodewijksz, the Latin name for the original source of the map.

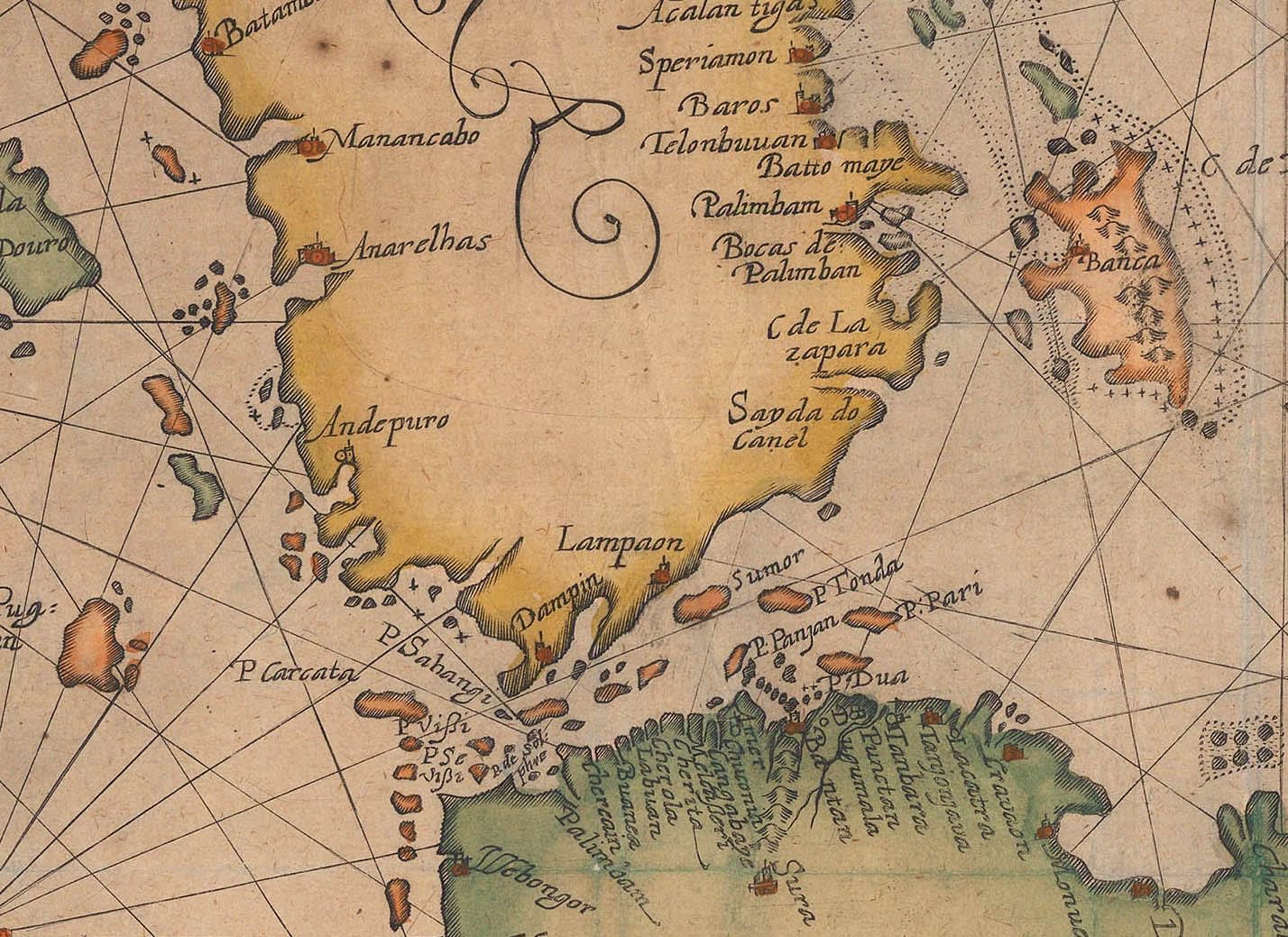

The greatest amount of detail is on the Northwestern coast of Java, with the large port of Bantan marked and numerous coastal settlements to its East and West. Slightly further to the West is an island named “P Carcata” which may be an early reference to Krakatoa, which is roughly in that location.

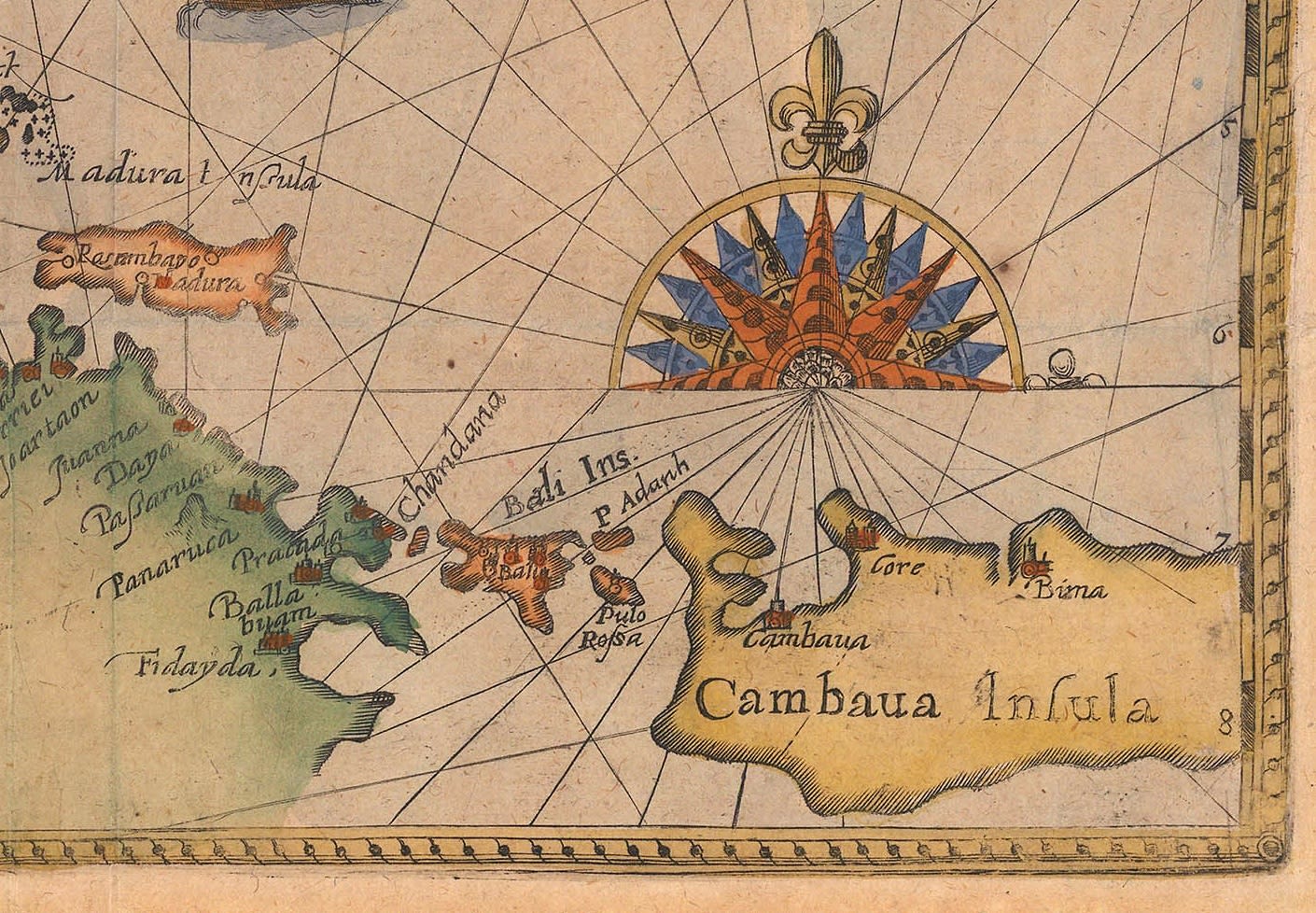

There is further detail on the North coast of Java, reflecting the route of de Houten’s expedition, as well as depictions of Bali and Sumbawa.

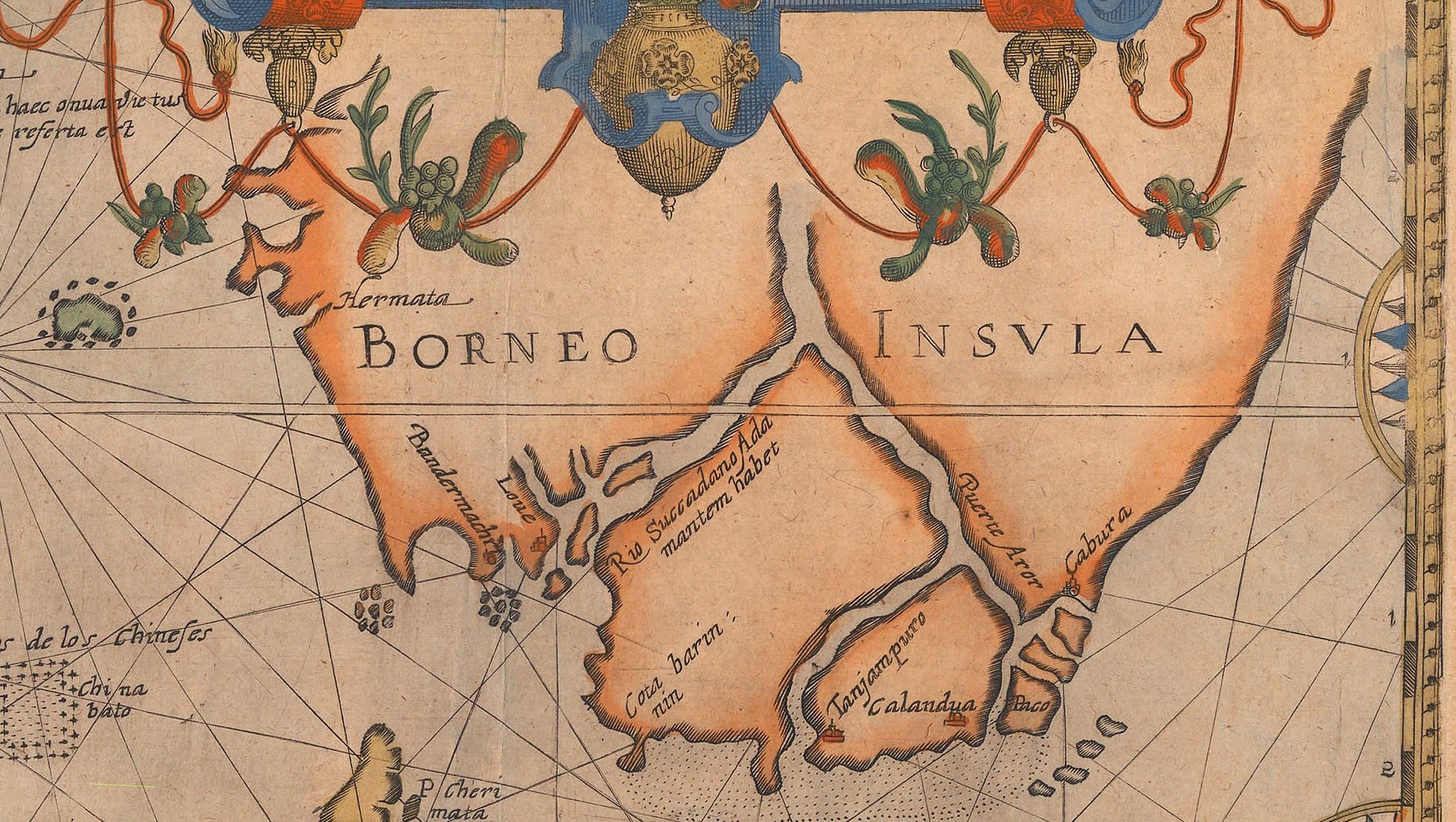

The Southern coast of Borneo is shown quite tentatively, with a huge river delta leading into the unknown interior. There is greater detail on the East coast of Sumatra, an area under the influence of the powerful Islamic Sultanate of Aceh.

The Southern tip of Malaya was not approached by de Houten and is thus far less accurately portrayed. The Straits of Singapore are shown as bisecting the landmass while Singapore itself is labelled as “c.de cincapura”, one of the earliest references to the city state. The whole region is named the “Chersonese Aurea” or Golden Chersonese, a name going back to Ptolemaic maps for the Malay Peninsula and a reference to the gold and general wealth associated with this region as far back as the Classical period.

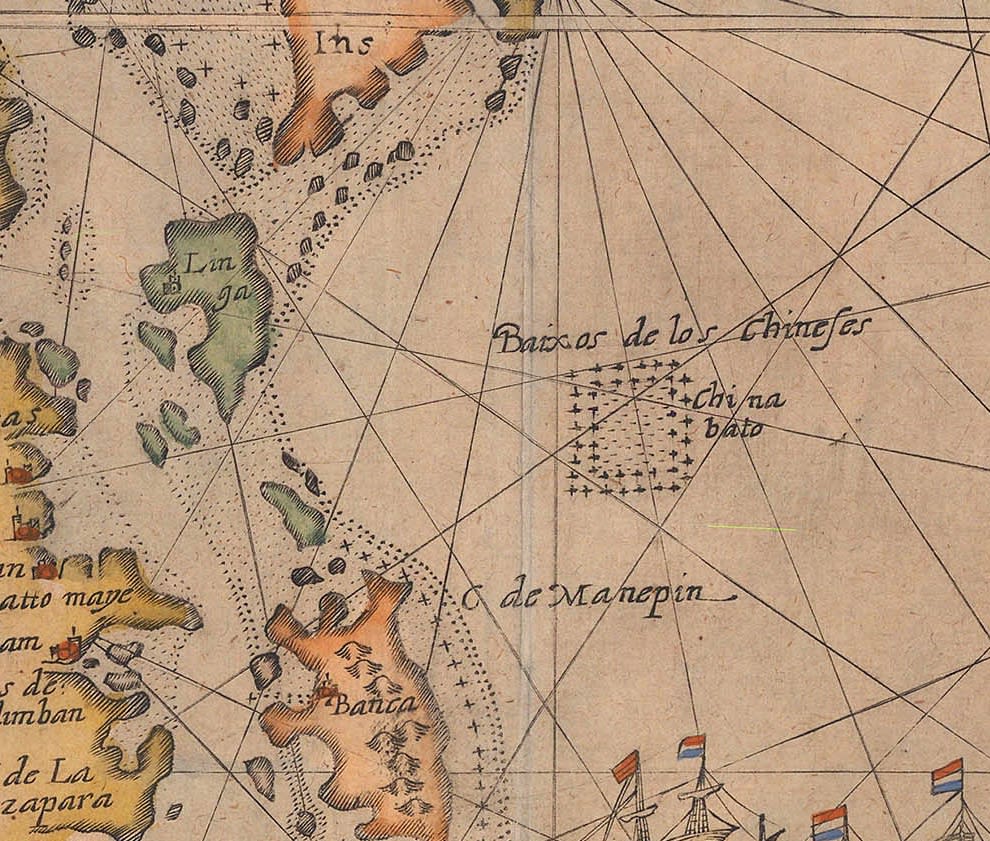

Finally, there is a peculiar feature, a small shaded square in the centre of the map, labelled “Baixos de los Chineses” with another note, “China Bato”; this may be a very early reference to the famous sea gypsies, a group of people known for their nomadic lifestyle on the sea that still exist today.

Little is known about Lodewijksz or his fate; his greatest claim to fame seems to be this map. Linschoten was also involved in attempts to find the Northeast Passage and sailed to the North Pole with Willem Barentsz; he retired to the town of his birth, Enkhuizen and passed away while in office as its Treasurer.

Cornelis de Houtman embarked on another journey to the East Indies. There, apparently again due to his demeanour, he became involved in a confrontation with the Sultanate of Aceh on Northern Sumatra. Ultimately, after a series of naval engagements in 1599, he died while suffering a defeat by the Acehnese navy commanded by the first female admiral of the modern age, Keumahayalati.

About the author

The Map House