For this entry into our blog, our emphasis moves to Africa, highlighting a series of maps which illustrate one of the most enduring and important quests recorded in the annals of exploration.

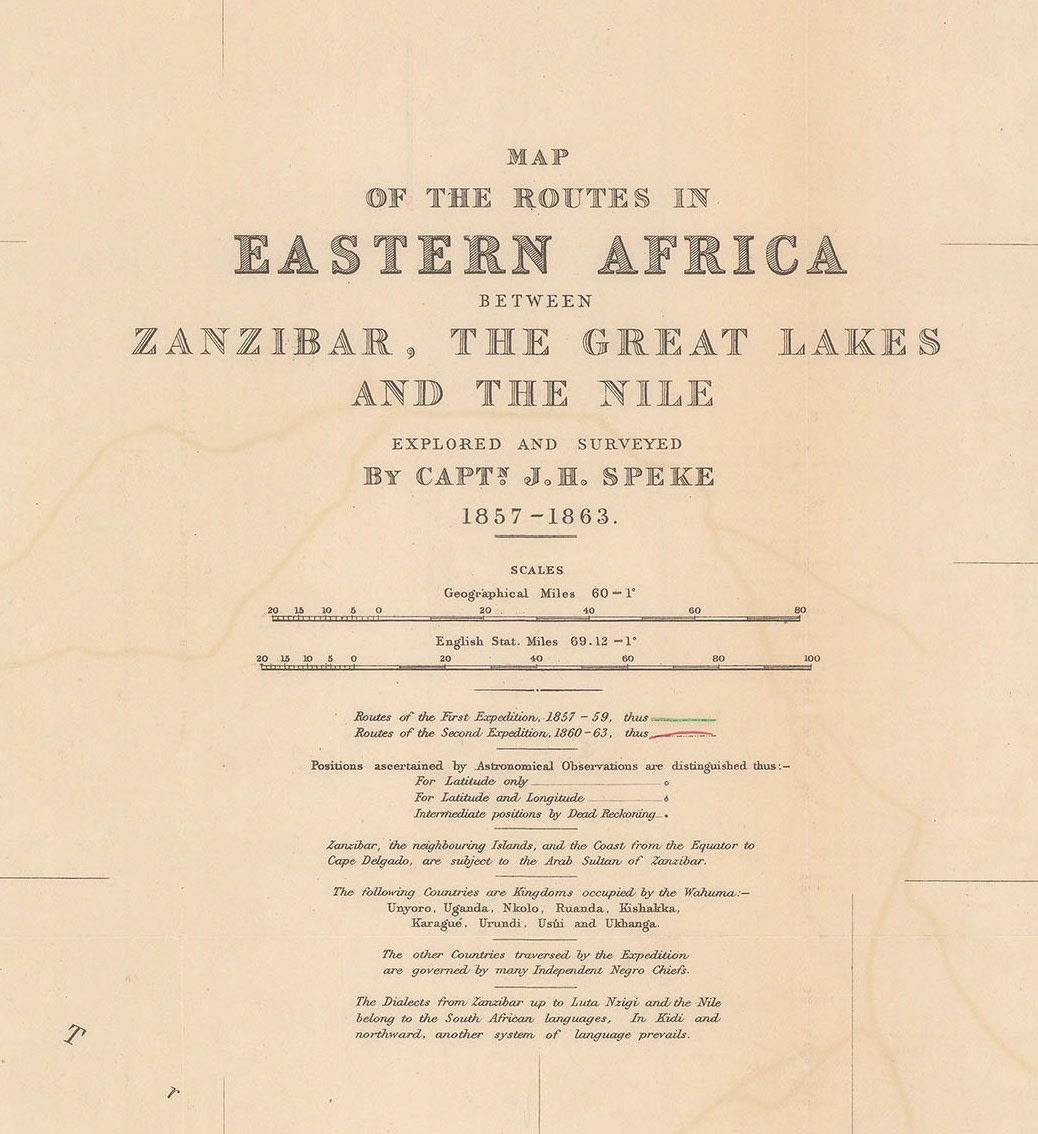

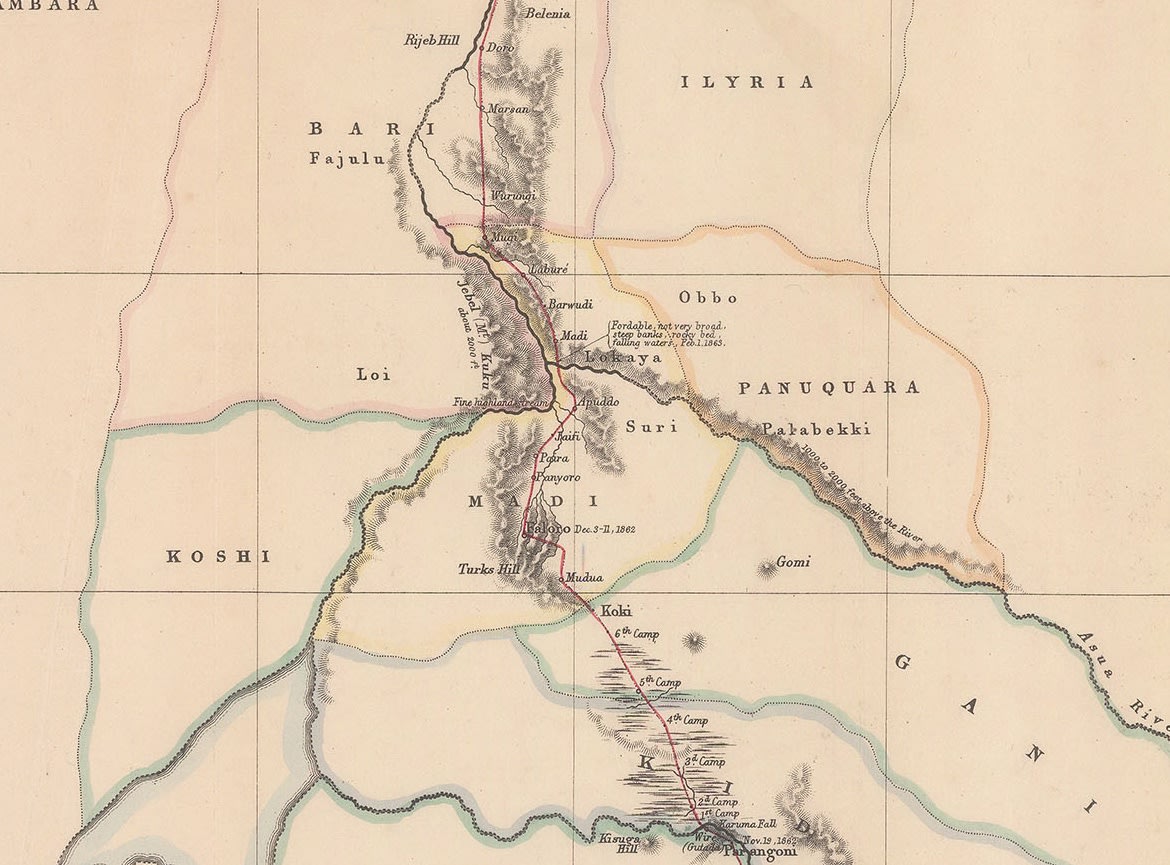

“Map of the Routes in Eastern Africa between Zanzibar, the Great Lakes and the Nile” by John Hanning Speke, published by the Royal Geographical Society in 1864.

The quest to discover the source of the Nile goes back centuries and the fascination that the river held for explorers and travellers throughout the ages cannot be truly summarised by one map. Therefore, in a departure from our usual entries in this blog, we have decided to highlight several maps from our inventory which showcase both the misconceptions and the gradual discovery of the elusive full course of the longest river in the world. These maps will illustrate the theories about its source from antiquity, to its actual controversial discovery and its aftermath.

“Presbiteri Iohannis sive Abissinorum Imperii Description” by Abraham Ortelius published in 1588.

To explorers, the discovery of the fabled source of the Nile was equal in importance to the locations of the Empire of Prester John and the legendary Seven Cities of Cibola, the discovery of the Northwest Passage and the search for El Dorado. In this case however, unlike some of the more esoteric aspirations mentioned above, empirical evidence demanded that the source of the Nile must be in the interior of Africa somewhere. Indeed, maps of Africa based on Ptolemy, the major cartographic authority surviving from the Roman period, show the river arising from two huge mysterious lakes placed in the interior of the continent.

“Hydrophylacium Africae precipuum in Montibus Lunae” by Athanasius Kircher published 1665.

Among many other theories, at the end seventeenth century the respected Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher speculated that the Nile was sourced from a vast underground lake under an enormous mountain range in South Central Africa, which he believed were the legendary Mountains of the Moon, another famous Ptolemaic feature on maps of the continent. This theory was based on the travels and accounts of Portuguese explorers who were also looking for the Empire of Prester John, a huge mythical Christian Empire, supposedly situated in the interior of Africa.

“Detailed Map of the Revd. Dr. Livingstone’s Route across Africa” by John Arrowsmith, published 1857. & “The Route of Mr. Mungo Park” by James Rennell, published 1798.

By the nineteenth century, spurred on by the major discoveries made by Mungo Park and Dr. David Livingstone, public anticipation associated with the search for the source of the Nile had reached a fevered level. The first European to reach the true source would go down in history alongside other legendary explorers such as Magellan and Marco Polo.

One of the more flamboyant characters associated with this search was Richard Francis Burton. Traveller, writer, soldier, explorer, spy, scholar, diplomat and above all, linguist, Burton is now correctly viewed as one of the towering figures of 19th century exploration. Born in Devon in 1821, but brought up in France, he showed an astonishing ability as a linguist; so much so that by the end of his life, he was reputed to be fluent in forty different languages and dialects. He left Merton College, Oxford in 1842 and joined the Indian Army. There, armed with enormous charisma and an extraordinary ability to blend into the local population, he embarked upon a series of adventures which soon made him one of the most famous men in London. He was also a gifted and prolific writer having authored or edited no less than forty three books by the end of his life in 1890.

In the mid-1850s, he had just returned from an incredible journey into Mecca, disguised as an Afghani Muslim. He had written an account of his adventures which was causing a sensation in the capitals of Europe as this was the most detailed European written work on the Islamic Holy City up to that time.

In 1854 he organised an expedition to cross Somaliland in East Africa; this was his first attempt to try to locate the source of the Nile. For this enterprise, Burton recruited John Hanning Speke, a fellow Indian Army Officer whom he had met at the British East India Station in Aden; Speke was a seasoned and experienced traveller, having been on expeditions to the Punjab and the Himalayas; whilst there, he had collected extensive samples of the local flora, fauna and geology. He was also a surveyor.

This expedition had barely embarked on its journey when it was attacked by hostile Somali tribesmen, possibly due to an earlier altercation between a local guide and Speke. Unfortunately, due to the injuries suffered by both Speke and Burton during the attack, the expedition had to be aborted. Speke returned to England to recover and then volunteered to serve in the Crimean War. Burton’s recovery took longer as he had been severely wounded in his jaw by a spear.

“Skizze einer Karte eines Theils von Ost u Central Afrika” by Justus Perthes published 1856.

Despite this early setback, the lure of the Nile was still very strong for Burton, especially as a major German publisher, Justus Perthes, had just produced a map of the mysterious Sea of Uniamesi, a vast inland sea purported to be in the centre of Africa. Reports of this mysterious body of water were brought back by German missionaries, who also speculated that it was the source of the Nile.

Therefore, in 1856, Burton began to organise another expedition to East Africa. He obtained funding from the Royal Geographical Society and again recruited Speke. Much has been written about Burton’s choice to add Speke to his expedition as some sources commented that tension between the two men had already become apparent and while it is impossible to ascertain the full reasons for this, it has to be remembered that at that time there were not that many individuals who possessed both his experience, skill set and willingness to undertake such a dangerous journey, especially after their initial attempt.

Setting out in 1857, unfortunately this expedition was problematic from the beginning. The tensions between Burton and Speke surfaced almost immediately. This in turn led to a lack of discipline within the organisational and administrative aspects of the expedition; there were numerous desertions of guides, guards and bearers. Simultaneous to these desertions were the mysterious disappearances of critical supplies which either went missing in the bush or were never delivered in the first place. These problems meant that that the expedition suffered extraordinary hardship and privation leading to both Europeans becoming extremely ill during their journey inland.

Marching over seven hundred miles east from Zanzibar into the unknown interior of Africa, Burton and Speke finally reached a huge lake, which they both hoped was the source of the Nile. However, before they could find the fabled mouth of the river, they had to resolve their dire personal situation. The lack of discipline within their personnel had grown to outright mutiny and Burton had almost lost his life when he had had to face down members of the expedition with a revolver in his hand. By now, he was so weak from malaria that he could not walk and had to be carried. Speke was also very weak and emaciated; although he was still mobile, he was temporarily struck blind due to opthalmia.

Thankfully, both of them recovered in a large Arab slavers’ camp on the shores of this newly discovered inland sea. In fact, Burton and Speke had just become the first Europeans in the modern age to reach Lake Tanganyika. Burton was still delirious and weak but he could move while Speke had recovered his sight after some rest. The expedition spent the next three months slowly exploring the coast of the Lake and looking for the elusive mouth of the Nile. Unfortunately, they had only brought a small canoe with them and this craft was not suitable for this kind of exploration. Local guides informed them that there was a major river mouth on the North shore of the Lake but they were also told that the river flowed into the Lake as opposed to out of it, which meant that it could not be the Nile. One of the peculiarities of the Nile is that it flows South to North; therefore, water had to be flowing out of its mouth as opposed to into it.

Disappointed and despondent, Burton and Speke concluded that their expedition had been a failure and it was time to return to Zanzibar. Yet Speke wanted eliminate one last possibility. While they were exploring the shores of Lake Tanganyika, local guides had mentioned another sea or lake further north and to the east. So, as they were travelling back, Speke took a brief solitary detour. Burton had fallen ill again and was too weak to travel with him.

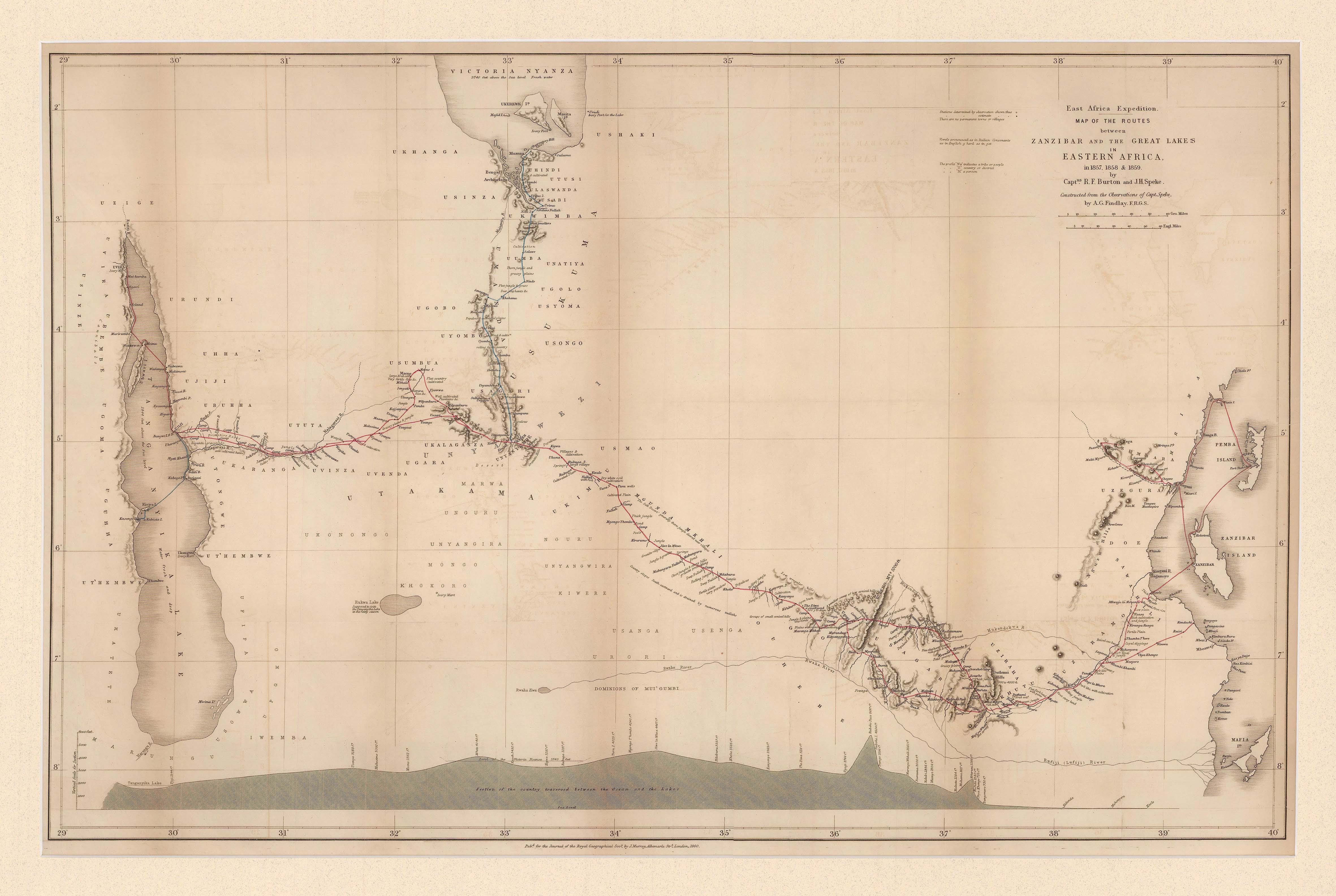

While Burton recovered in Kaze or Taboro, labelled “Arab Settlement” on the map above but now modern Tabora in Tanzania, Speke travelled North for over a month, as shown by the green line on the map. On August 4th, 1858, he arrived at a high point, which he named Observatory Hill and overlooked a vast expanse of blue water. Immediately, he named it Lake Victoria in honour of the Queen. Thus, Speke became the first European in modern times to reach Lake Victoria.

More importantly, Speke became absolutely convinced this was the source of the Nile.

Having determined the position of the lake, Speke returned to Taboro. Due to their previous difficulties, the expedition was unable to detour and explore Speke’s discovery as both men were on the verge of physical collapse. Finally, starved, ill and exhausted, the expedition returned to Zanzibar. As soon as they had done so, Burton sent a letter to the Royal Geographical Society, enclosing a brief report of the expedition as well as a very rough sketch map of Speke’s trip to Lake Victoria with a comment that it was very likely that this vast lake was the source of the Nile. They then sailed North to Aden.

It is here and at this point that one of the most controversial events in the whole affair supposedly took place. Burton was weaker than Speke and at that time, unfit to travel. Speke wanted to return to England; apparently, before he left, Burton and Speke made a verbal gentleman’s agreement that the latter would wait until Burton returned to London before making a joint formal report to the Royal Geographical Society of the results of their expedition. Unfortunately, as with many claims and counter claims by the partisans in this affair, it has not been possible to prove this one way or the other.

Speke arrived in England on May 8th 1859 to a rapturous reception. He was lionised by society and sought as an authority; he was immediately offered a contract to write an account of the expedition, invited to lecture at the Royal Geographical Society and to contribute to their Journal.

In short, he was enjoying the fruits of being the discoverer of the source of the Nile.

Burton arrived back in England on May 21st, to find that to all intents and purposes Speke had usurped his position as leader of the expedition. It should be remembered at this point that Burton was the driving force behind the project; it was due to his fame and experience that the Royal Geographical Society had decided to finance the enterprise, it would have been Burton on whom they would have relied as the leader and organiser and there was also no doubt that it was Burton who would have been the point of contact for the Society. Speke was someone whom Burton had recruited after the decision to undertake and finance the expedition had already been taken.

Angrily, Burton reversed his position on Lake Victoria and stated that he now had his doubts about its authenticity as the source of the Nile. He also stated that Speke certainly had no scientific evidence to support his claim. He had not found the mouth of the river, nor even any evidence for its existence. Ultimately, all he had found was another large inland lake in Africa. So far as he was concerned, that was a huge step from finding the source of the river.

One of the difficulties in this matter is that it is impossible to know just how proactive Speke was in promoting himself; was he just being swept along by events, driven mainly by the Royal Geographical Society’s desire to be perceived as the academic body which sponsored the first successful expedition to make this long cherished discovery? Or maybe he was being promoted by his new publishers, who would want all the free publicity they could get? Or did he actively set out to claim a position as the sole discoverer of the source of the Nile, taking advantage of Burton’s absence?

However Speke comported himself, there was no doubt that a major breach was taking place between the two expedition members. Both were highly gifted, strong willed and intelligent individuals who were extraordinary in their ways and both strongly believed in their own convictions.

“East Africa Expedition – Map of the Routes between Zanzibar and the Great lakes in Eastern Africa” by A.G. Findlay and published by the Royal Geographical Society 1860.

Shortly after his return, Speke contributed an article illustrated by a map to the Geographical Journal in 1860. It is notable that the map, illustrated above, is “constructed from the observations of Captain Speke”. Although the map does credit both men as participating in the East African Expedition, there is no mention of Burton contributing to its cartography.

Contemporary sources note that Burton was more socially adept and verbally agile than Speke and he continually cast doubt upon the latter’s theory. Journalists, scientists and writers began to take sides in the dispute and in some cases to provoke it as it helped to sell newspapers. It must have rankled Speke to have his theory unproven as he had a scientific background and although he was convinced of his own claim, he must have still been aware that in fact he did not have any scientific proof, just his own cast iron belief and intuition. At the same time, the Royal Geographical Society itself must have been irritated that one of its greatest triumphs had become so mired in controversy.

Matters finally came to a head and the Society decided that it was imperative that another expedition be dispatched forthwith to settle the matter one way or another. Without a doubt it had to be led by either Burton or Speke though under the circumstances, another joint expedition was out of the question. Again, there is another controversy here as supporters of Burton claimed that the Society favoured Speke as it was rankled by Burton’s vociferous criticisms of Speke’s and indirectly its claims. However, it also has to be noted that Burton had still not recovered from the malaria that he had contracted in Africa previously and he was far from well, visibly so. The Society came to the decision to award the expedition to Speke, to the bitter disappointment of Burton.

Speke rapidly began organising his new expedition; he recruited a fellow Indian army officer, James Augustus Grant, to join him. Grant was an old acquaintance and contemporary sources cite him as being extraordinarily patient, stoic and serene; character traits which would dovetail very well with Speke.

Mindful of the deprivations he suffered previously, Speke also arranged for supplies to be shipped to Gondokoro, a trading post on the Nile in the Sudan. This was the most southern settlement which was reachable by steamers from the Mediterranean. Speke was fortunate that John Petherick, vice consul and soon to be full British consul in Khartoum, was in London at this time.

Petherick was a Welshman who trained as a miner. Initially, he was invited to Egypt to search for coal but unfortunately, his survey was negative. During his time there, he became fascinated with Africa and stayed in the region, becoming a gum arabic trader. Initially he was successful but then that commodity suffered an oversupply so he turned to trading in ivory. His activities involved a great deal of travel and he had just returned from a difficult journey to the remote Bhar El Ghazal region in modern South Sudan. He was in London partly to be promoted to full consul of Khartoum and also to get married.

He was entrusted with one thousand pounds to provide a relief caravan for the expedition. The arrangement was that the supplies would be waiting for Speke in Gondokoro.

Finally, with all these arrangements in place, the expedition set out from Zanzibar in late 1860. As previously, it was beset with problems from the start. Some of these were extraneous issues over which they had no control but others were of their own making.

There was a great deal of local unrest in the region. Some of it was caused by local conflict and some of it was caused by the activities of Arab slavers. This caused a great deal of distrust of foreigners in general and it was a persistent cause for delay during the duration of the expedition.

Speke also vastly underestimated the amount of tribute he would have to pay to pass through the lands of local chieftains. This was an odd omission, bearing in mind that a large part of the route of the expedition re-traced the footsteps of his previous journey with Burton.

Simultaneously, Grant fell ill almost immediately and throughout most of the expedition, he suffered from a collection of maladies from inflamed wounds to malaria. The two men spent a great deal of time apart, partly due to Grant’s illness and partly due to another endemic problem which was the retention of hired personnel.

There are various references that the caravan had to be divided or a large quantity of the supplies had to be left behind under the care of Grant for long periods of time while Speke attempted to recruit local tribesmen. It seems that it was very hard for Speke to keep his original employees. This delayed their progress even further and they did not see Lake Victoria until 1862.

The introductory map to this article notes quite clearly the place (Mashonde) and the date (Jan 28th 1862.)

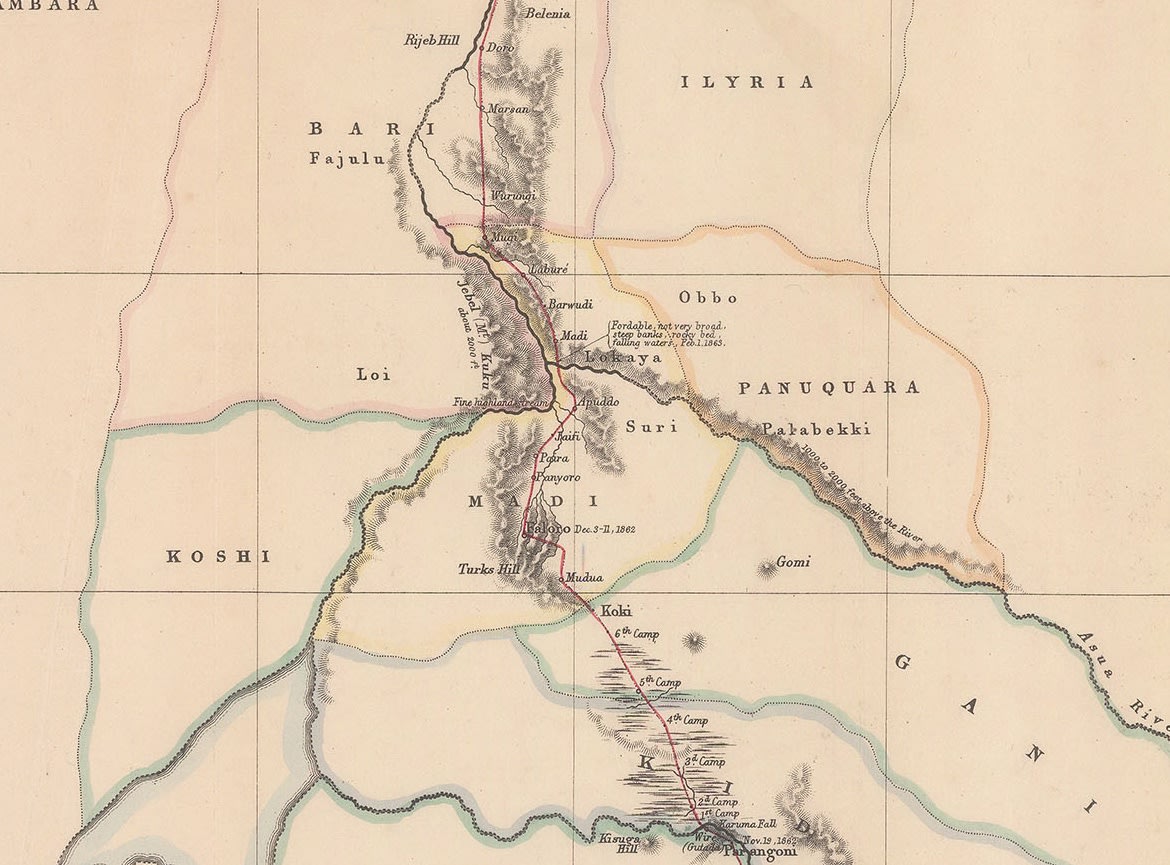

As the map above indicates, the expedition followed the Western shore of the Lake and, after spending some time at the settlement of a chieftain named Mtesa, on July 28th 1862 Speke finally reached the Northern shore of Lake Victoria at a point where a series of spectacular water falls showed a large river flowing north. In light of the peculiarity mentioned previously regarding the flow of the Nile, this could only be its source!

He named the mouth of the river the Ripon Falls, after George Robinson, Marquess of Ripon.

Speke had finally accomplished his dream; he was convinced he had found the source of the Nile but now he had to prove it by following the river northwards to a known section of the river. Again, as the map shows he did so for some distance, spending just over two weeks following it but then, he made a fateful decision. He deviated from its physical course.

There has been much speculation as to why Speke decided to deviate from the course of the river. While it is impossible to say exactly what was on his mind, there are a variety of factors which must have influenced this decision.

Above all, there was his logistical situation. His supplies were dangerously low and both he and Grant were on the edge of starvation. The topographical environment was extremely difficult. Local unrest, both due to the activities of slavers and tribal warfare, continued to be a major hazard. He was running out of tribute or “gifts”. He had had to part with his last and best chronometer as a gift to Kamrasi, one of the most powerful local rulers.

Simultaneously, local guides assured him that this river was connected to a large river further north which also flowed away from the lake or South to North. That was an unusual feature and he must have felt that it was very unlikely that there were two large rivers with this peculiarity in the region. After all, he had located the mouth of the river at Lake Victoria and he now wanted to connect it to the known Nile; while desirable, it was not absolutely necessary for him to map its exact course after finding the source. Finally, he also must have been aware that his expedition was greatly overdue.

Speke joined the river again in the lands of the aforementioned Kamrasi. According to Speke’s Journal, negotiation with Kamrasi, a local ruler, were particularly difficult both initially to enter his domain and then to leave it; hence the reason why the expedition stayed there for two months. Speke followed the river until the Karuma Falls, where again, relying on local guides who informed him that the river continued North, he decided to deviate from its course and rather than follow the river West, strike North.

On this occasion, local environmental conditions must have played a part in his decision. The Nile drops down precipitously at the Karuma Falls, and then becomes a series of dangerous cataracts caused by numerous semi submerged rocks. Today, this is a spectacular natural feature and a major tourist attraction but in 1862, it must have been a disheartening sight for an expedition that was very overdue, under supplied and lacking in any specialist climbing knowledge or equipment.

Again, local guides must have also have informed him that further ahead there was another set of steep falls; these were to be later named the Murchison Falls, after Sir Roderick Murchison. In reality they drop approximately forty meters in a gap only seven meters wide. Speke did not actually see them but it is very likely that he was informed about this hazard.

The snapshot of the map above also counters another claim; namely that Speke was unaware of the importance that a large body of water to the Northwest of Lake Victoria played in determining the course of the river. As the map above shows, although Speke decided not to travel there, again probably due to a combination of the reasons stated above, he was certainly aware of it, drawing its position on his map, albeit with dotted lines used in its outline, indicating that this was rough reckoning. He used its local name, Little Luta Nzige Lake, which translates into Dead Locust Lake. More importantly, he clearly shows a probable course of the Nile going into this lake and then flowing out again in the Northeast.

As mentioned above, Speke joined the river at a point further North, where it was much calmer, and followed its course to Gondokoro, finally proving his theory.

It was upon reaching Gondokoro that another great controversy occurs in this narrative.

As mentioned above, Speke and the Royal Geographical Society had arranged for John Petherick to send a relief caravan of supplies to the expedition. Although the supplies were there, Petherick and his wife were not. Speke was extremely vocal in expressing his disappointment that the Pethericks were not there to greet him in person. So much so that he decided that Petherick had kept the Society’s money and defaulted on his agreement, calling him “a false man.”

By coincidence, another famous explorer had arrived at Gondokoro, also interested in tracing the source of the Nile: Samuel Baker and his common-law wife, Florence von Sass. This couple are an extraordinary story in themselves. Baker first saw Florence in a Bulgarian slave market, for sale. It was love at first sight for both of them and, after being outbid in the slave auction by the Turkish Pasha of Vidin, Baker stole her and escaped to Africa. His companion in this escapade was the Maharajah Duleep Singh, the last surviving son of Ranjit Singh, the Lion of the Punjab, who did not go with them but rather returned to England.

The couple were here on their own expedition and Baker eagerly offered Speke and Grant the hospitality of his camp, very interested to hear about their experiences and extraordinary achievement. Speke accepted, still feeling betrayed by Petherick and forcefully proclaiming that the latter was not a man of his word, a serious accusation against the British Consul of Khartoum.

There was no great mystery to the whereabouts of Petherick; he had an elephant hunting camp nearby as part of his business enterprise. Just before reaching Gondokoro, he and his wife Katharine travelled west to inspect and oversee its activities. Once he had completed this, he continued to Gondokoro and reached the settlement a day after Speke only to find himself accused of fraud.

It is difficult to know what was going on in Speke’s mind at this point and why he felt that it was it so necessary for Petherick to meet him, but one of the factors that should be taken into account is the difference in background between the two men. Petheric was a blunt, self-made man who oversaw a large business enterprise under difficult circumstances in Egypt and the Sudan. He travelled extensively in the bush but mainly for business purposes and he was commercially astute; in short, he was a successful businessman. A contemporary described him as a “kind-hearted, plucky, powerfully built specimen of true John Bull”.

Speke came from an old and respected family in Devon and was an army officer. His search for the Nile had become an obsession, the most important thing in his life, especially after the bruising dispute with Burton. His arrival in Gondokoro was his triumph, his validation, his proof. As Consul, Petherick would have been the closest thing to the British establishment there and someone to whom Speke could relate his momentous discovery.

Unfortunately for Speke, it may be that Petherick did not share his obsession and that there was a divergence of perceptions. For Petherick, the delivery of the supplies may have been just another business transaction. In fact, bearing in mind that Speke was over a year late, that the Pethericks almost died in an accident on their journey South, that the supplies had been delivered on time and that a group of guides had been sent to find Speke before he reached Gondokoro, Petherick had some justification to feel bewildered by the accusations heaped upon him on his arrival.

Although this may have explained Speke’s initial, possibly feverish, reaction, it does not explain his further actions. Upon being informed that the supplies were in fact there, waiting for him as arranged, he stated that he wanted nothing more to do with Petherick or the supplies and that he would rely on “his good friend Baker” from now on.

Speke and Grant travelled to Khartoum with Baker on his steamer and upon reaching the city, sent a famous telegram to London, “The Nile is Settled.”

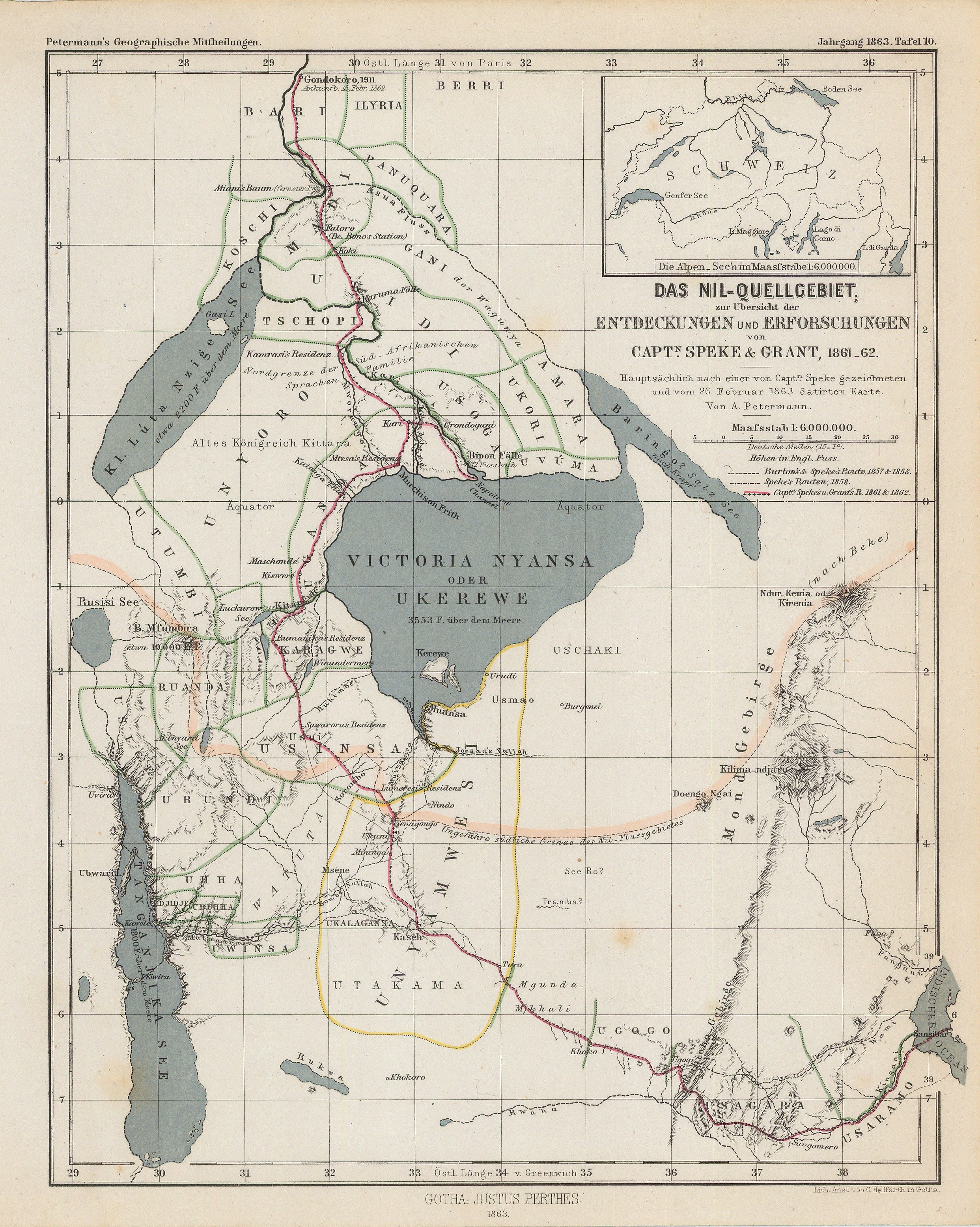

[“Das Nil-Quellgebiet, zur Ubersicht der Entdeckungen und Erforschungen von Capt. Speke & Grant, 1861-62”]

Speke and Grant returned to London in 1863, again to adulation. Speke published his Journals, which he kept during the expedition. Two maps were bound with these books and these were widely copied on the continent with versions appearing in Augustus Petermann’s famous and respected German geographical journal, “Geographische Mitteilungen” among many others.

Despite this initial adulation, there were storm clouds on the horizon. Burton read through Speke’s journal and claimed that Speke had still not produced scientific evidence that Lake Victoria was the source of the Nile. Yes, the river that flowed North at the Ripon Falls bore the characteristics of the Nile but since Speke had not followed its course faithfully to Gondokoro, his assertions that he had finally found the source had not been proven. Admittedly, even neutral observers of the time stated that Speke’s Journals seemed to concentrate heavily on ethnographic commentary and very lightly on the geographical and scientific evidence for his assertion that he had found the source of the Nile.

Speke still bore a grudge against the Pethericks but their supporters were demanding an explanation for his conduct.

He was also coming under pressure from his publisher, William Blackwood to fulfil his contract and he was very late in producing his report for the Royal Geographical Society, including a map specifically done for their Journal. Again, they must have found it quite galling to see that Petermann’s Mitteilungen was producing maps of an expedition they had sponsored and they had nothing to show their members.

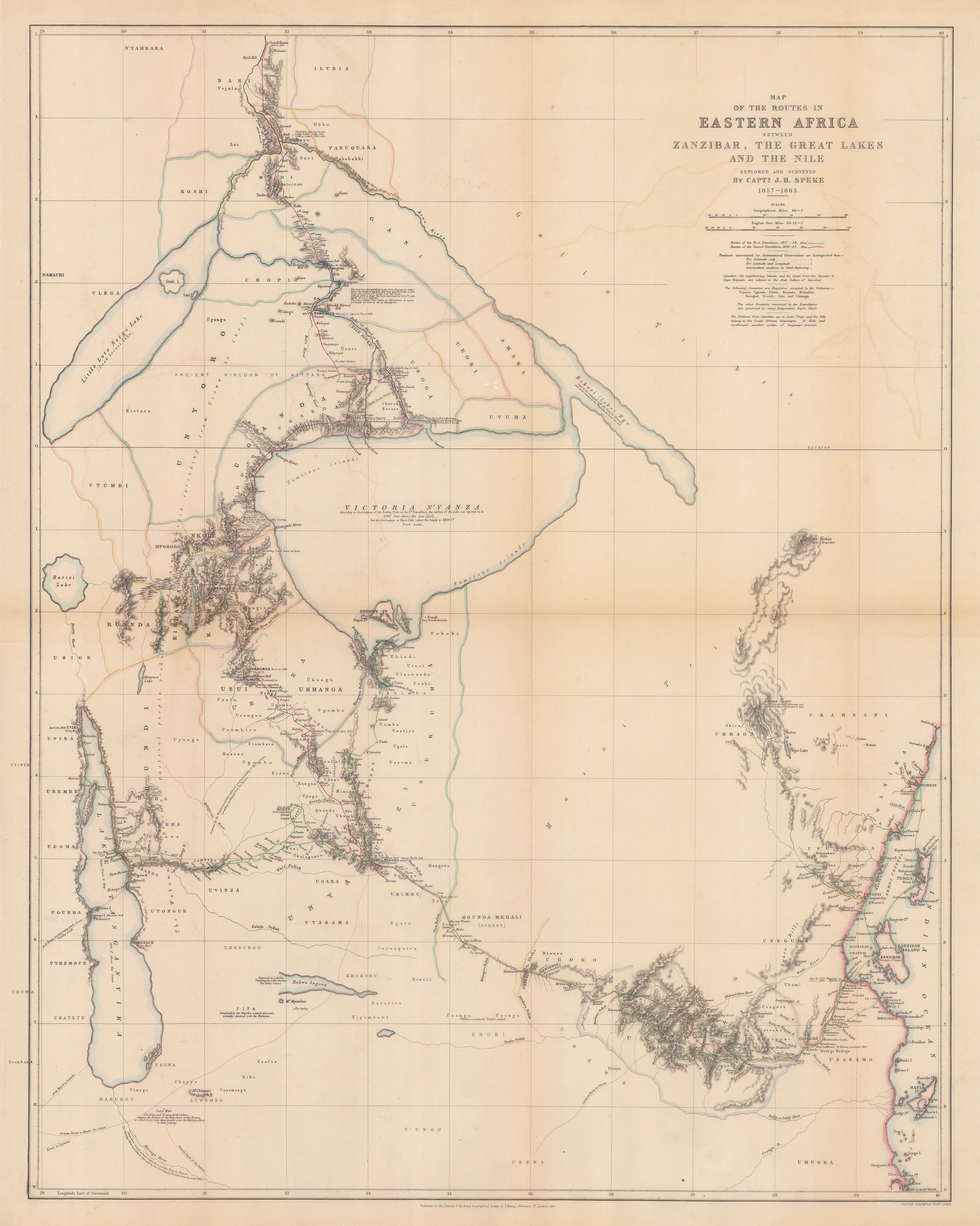

Thankfully, Speke finally did produce a map for the Society in 1864. This is the piece which introduces this article and it was certainly worth the wait; it is a large, beautifully engraved scientific document which encapsulates the full extent of both momentous expeditions with extraordinary detail and additional data from Speke’s diaries which note the location of the camps, the local settlements, the palaces of the local chieftains, important dates and, most importantly of all, that contentious route of the second expedition on the North shore of Lake Victoria is clearly shown.

One extraordinary omission on this map is to be found in the nomenclature used in the title:

“Map of the Routes in Eastern Africa between Zanzibar, the Great Lakes and the Nile, explored and surveyed by Capt. J.H. Speke, 1857-1863.” There are two coloured routes, one showing the route of the first expedition in green and dated 1857-59 and the other showing the route of the second expedition and dated 1860-63.

Tellingly, there is no mention of Burton, or Grant for that matter.

Finally, exasperated by the course of events, the Royal Geographical Society suggested that Burton and Speke hold a public debate to try and settle their dispute once and for all. This would certainly not have pleased Speke; as has been stated previously, Burton was a skilled and charismatic debater. However, Speke was convinced of his findings and that the evidence that he could produce would persuade both the public and the scientific community that he had found the source of the Nile. Even more importantly, he could call on Grant to support and validate his evidence.

The date of the debate was set for the 16th of September 1864, in the town of Bath, Somerset, at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Speke travelled down to the city on the 15th to attend a preliminary presentation and in the afternoon, went to stay with his uncle in Neston Park, Wiltshire.

The next day, while Burton and the public were waiting for his arrival, momentous news arrived. Speke had been out hunting with his cousin, George Fuller and suffered an accident. He had fallen while climbing a wall and accidentally shot himself. According to a contemporary account, he survived for about a quarter of an hour before succumbing to his wound.

Almost immediately, rumours appeared that Speke’s evidence was not nearly as compelling as he believed and that he would rather take his own life than face public ridicule. These rumours have now been generally discarded, mainly due to the position of the wound, which was under the left armpit, a very difficult and peculiar position to reach if one had a mind to take one’s own life with a shotgun.

Despite Speke’s conviction that “The Nile is Settled” as he put it, there are several fascinating post scripts to the search for the source after he left Africa for the second time.

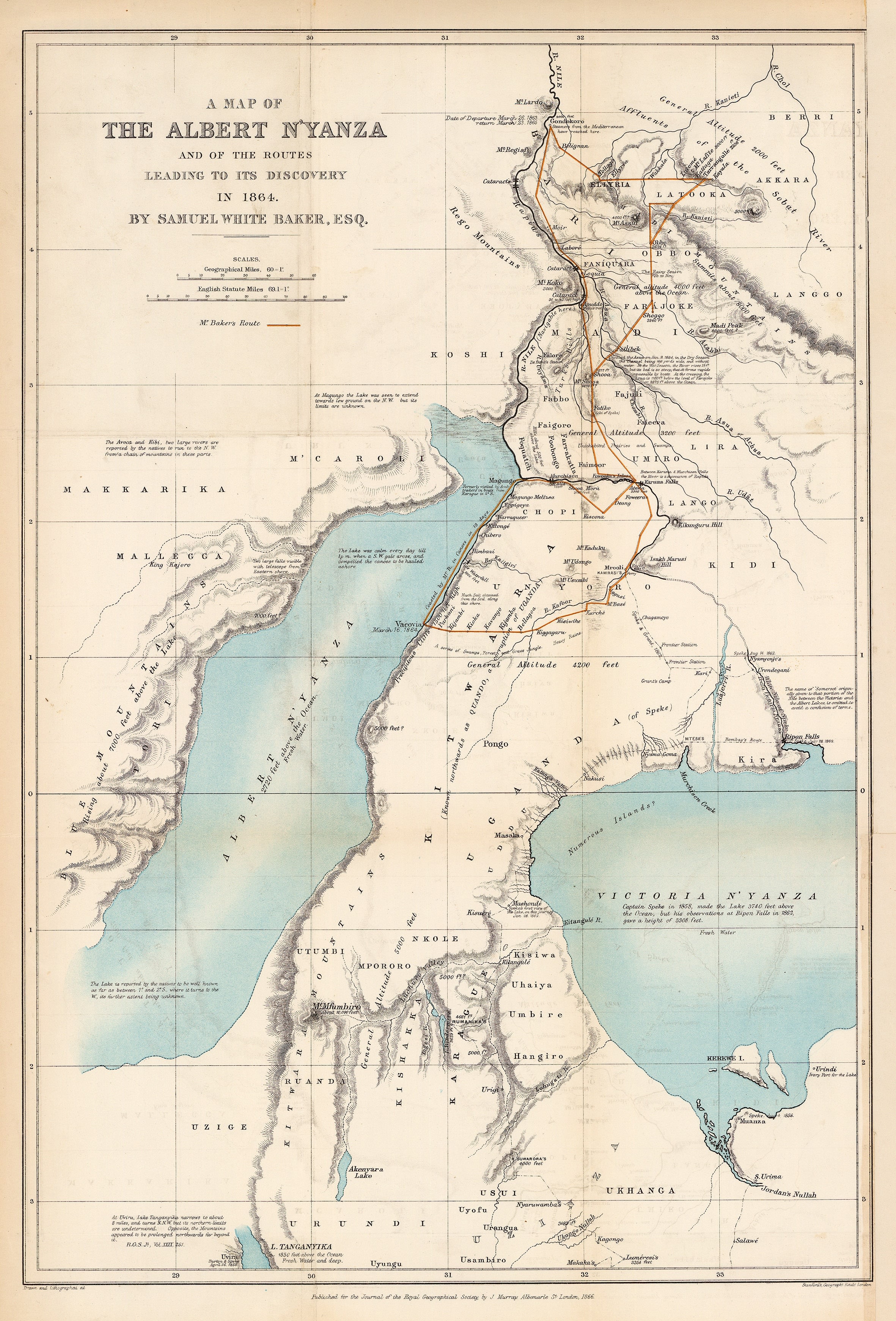

“A Map of The Albert N’Yanza and of the routes leading to its discovery in 1864.” Samuel White Baker, Esq. published by the Royal Geographical Society 1866.

Samuel Baker and Florence von Sass embarked upon their own expedition to the South. Enthused and informed by their conversations with Speke and Grant, they set out and reached the Karuma Falls where they followed the Nile West, noting that after these Falls the river became a series of dangerous cataracts which ended in a spectacular waterfall, which they named Murchison Falls.

Following the river further west and after suffering much hardship, they reached the large lake that had been mentioned by Speke. They became the first Europeans in the modern age to reach this lake and named it Lake Albert, in honour of Queen Victoria’s consort. After exploring this new lake, they were also able to establish that the Nile flowed through it on its way to the Mediterranean, thus scientifically proving Speke’s theory. As they state on the map, the section North of Lake Albert is navigable.

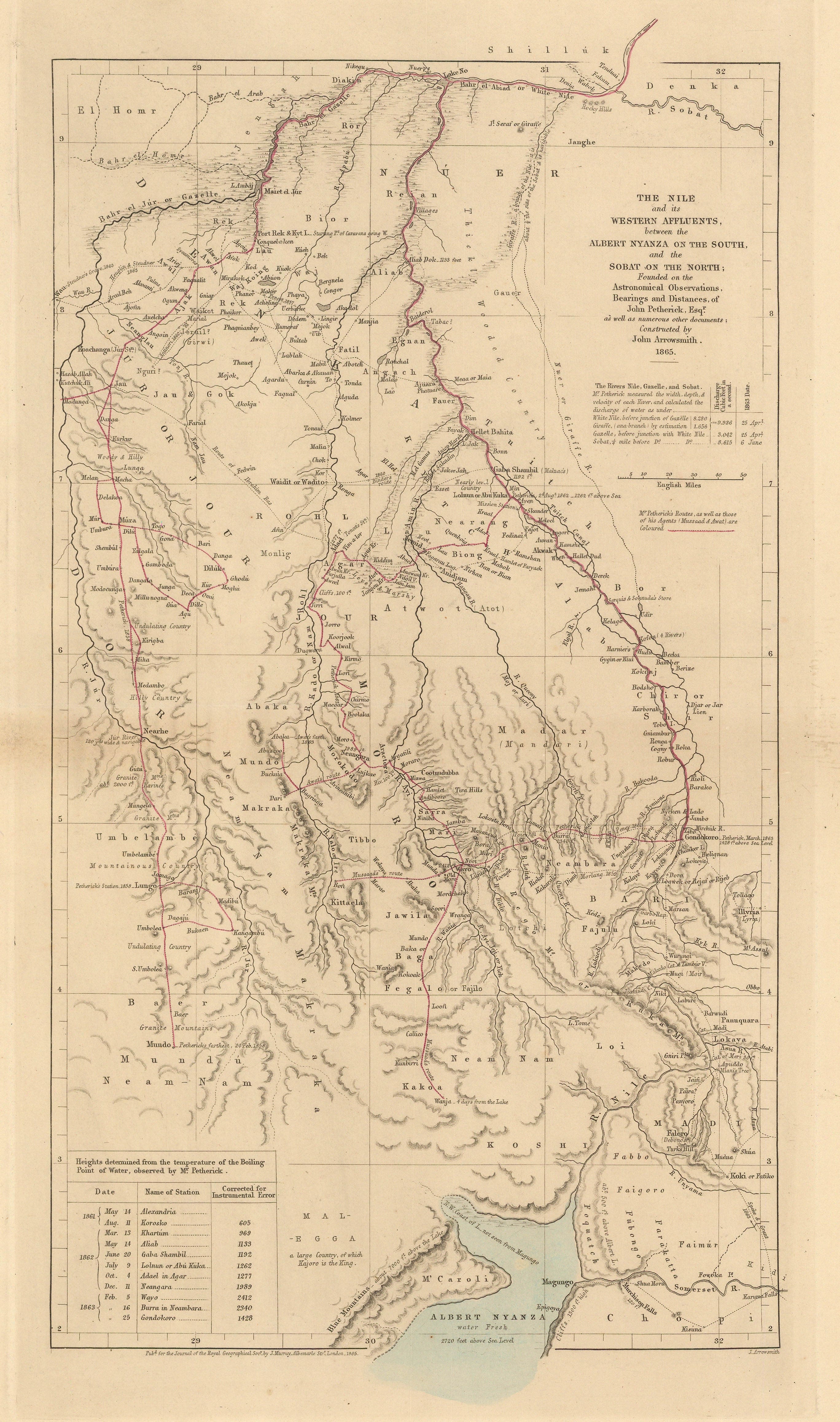

“The Nile and Western Affluents between the Albert Nyanza on the South and the Sorat on the North” by John Arrowsmith, based on John Petherick’s documents, published by the Royal Geographical Society 1865.

John and Katharine Petherick were ill served by Speke. As they were returning from Gondokoro, they found that one of their agents and his partner were using their vessel for slave trading. They captured him and sent him to Khartoum to be tried. Unfortunately, they were unable to accompany the accused, upon reaching the city, he, in turn, accused them slave trading. He was promptly set free and disappeared while the Pethericks themselves were investigated upon their return.

This whole affair became very murky. According to the laws of the British Empire, it was illegal to participate in slave trading. It was also the duty of all citizens to report and try to stop this trade. In fact, Petherick was notorious for arresting and accusing individuals for this crime, although it has also been suggested that he used this to eliminate business rivals. However, the reality was that Khartoum was a slave trading city and most of the commerce within it relied on this trade. Repercussions from Petherick’s arrests were not only felt in Khartoum but also as far as Egypt. His enemies seized upon Speke’s accusations of fraud to combine them together with their accusations of slave trading to the extent that Speke also believed that Petherick was guilty of participating in the slave trade. Speke even sent a telegram to Sir Roderick Murchison, the president of the Royal Geographical Society, denouncing Petherick in such strident language that Murchison kept it confidential, concerned that it would be Speke himself who would be harmed.

The whole situation became so toxic that Lord Russell, the Foreign Secretary, closed the Consul’s Residence in Khartoum and summoned Petherick back to London.

As can be seen from the map above, which illustrates Petherick’s not inconsiderable contribution to the geographical knowledge of the origins of the Nile, the Royal Geographical Society certainly considered Petherick as someone worthy to contribute to their Journal only a year after Speke’s death. Unfortunately, Petherick always claimed that his reputation was permanently damaged by Speke’s accusations.

Ultimately, it is historically generally accepted that Speke was the first European to have found the source of the Nile where the river actually takes shape; the section between Lakes Victoria and Albert has become known as the Victoria Nile to differentiate it from the section that flows North of Lake Albert which has become known as the Albert Nile.

Hydrographically however, Lake Victoria has several feeder rivers, which could be interpreted as being part of the Nile. The major feeder river which has been identified is the River Kagera or the Alexandra Nile, but it itself has several tributaries.

An expedition traced what they believed was the longest of these tributaries, the River Rukarara in Rwanda. After trekking up a mountain slope and hacking through the jungle, they found an area where an appreciable amount of water seeped from the ground. At the moment, this is believed to be the point where the Nile actually surfaces from the earth, as predicted by Athanasius Kircher three centuries ago. The distance from the mouth to this source is 4199 miles or 6758km. The above expedition made this discovery in 2010.

If you would like more information about any of the fascinating maps mentioned in this article, please email

maps@themaphouse.com, and to find more maps detailing this area please click here.

About the author

The Map House