What is in no doubt is that it was due to their collective efforts that the United Kingdom suddenly burst upon the cartographical industry from the 1770s onwards, dispensing with many geographical legacy myths as well as introducing exciting new discoveries which revolutionised geography. An increasingly sophisticated public with an ever growing thirst for the scientific and the exotic made for an exacting taskmaster, but it was this thirst which drove these map makers to new heights of scholarship and precision.

Public Domain image of Aaron Arrowsmith.

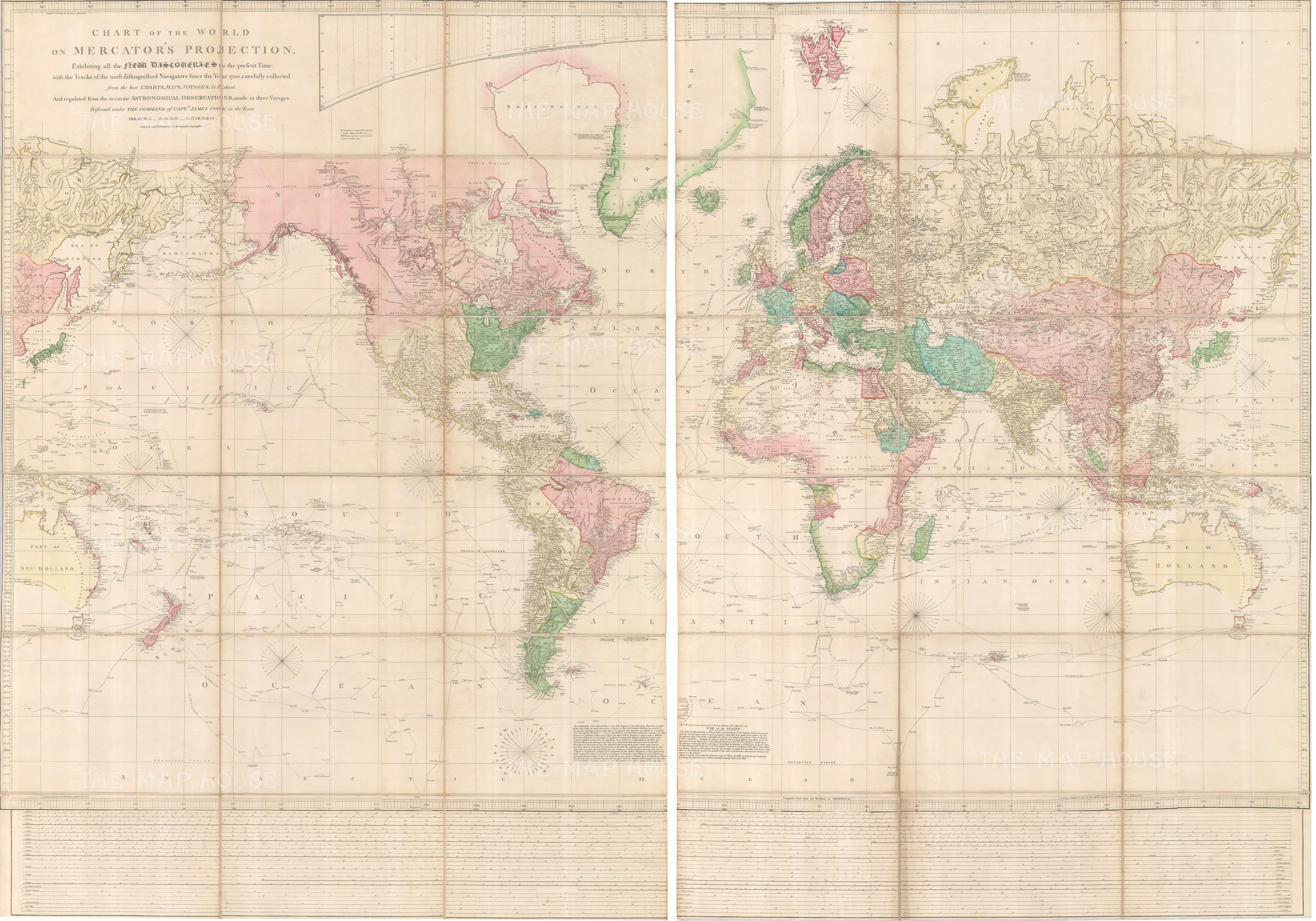

Arrowsmith was at the forefront of this movement. His birth year has been tracked down to 1750 in Winston, County Durham but little is known about his youth. Evidently he moved to London, as in 1777 he was cited as a witness for the will of another map maker, Andrew Dury and in the next few years, there were records of him associating with William Faden, although it is not clear in what capacity. He is also recorded to have worked extensively for John Cary as a surveyor, both on his survey of the post roads of Great Britain between London and Falmouth of 1784 and his county atlas of 1787 respectively. It is believed that he founded his own business in 1790 and his first project “A Chart of the World on Mercator’s Projection”, set a standard for which the firm became unforgettable.

This map was followed by a collection of large, usually linen backed, segmented wall maps of many parts of the world, some so specific that it was obvious that they were individual commissions and separately issued. Although the firm did produce books and atlases, their emphasis was on their wall maps. By their very nature, these pieces are ephemeral, difficult to trace and extremely rare in today’s market for the collector. These are the reasons that make them so very desirable, important and collectable. Arrowsmith’s scholarship and access was unrivalled; he seems to have been able to consult the records and manuscripts of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company; he was used by Hansard as a cartographer for the then fledgling Parliamentary Papers, which gave him access to manuscripts produced by the Army, the Navy and multiple civilian sources abroad archived by the British Government. He also must have built up an enviable network of colleagues and researchers in his earlier years while working for Faden et al. He made extensive use of this network as his maps are famous for the diligence in which he portrayed the most recent and up to date information that was available, often on a map he himself had issued previously, creating a continuous cycle of revisions and updates. The firm prospered until Aaron’s death in 1823 whereupon it was taken over by his two sons Aaron II and Samuel. Under their stewardship, it never reached the same heights, but in 1839 it was taken over by John Arrowsmith, Aaron Senior’s nephew, who reinvigorated it and continued its upward trajectory until his death in 1873, when the firm was sold to another important cartographic business, Edward Stanford Ltd.

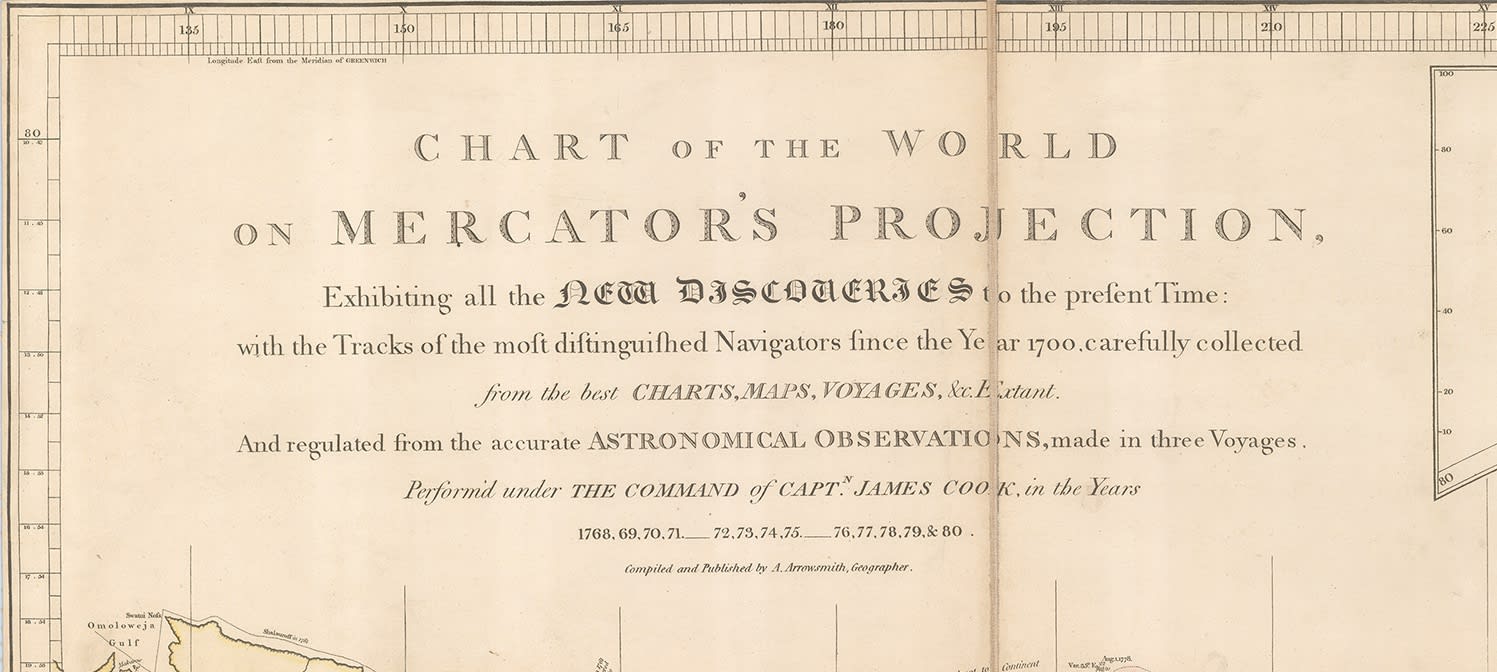

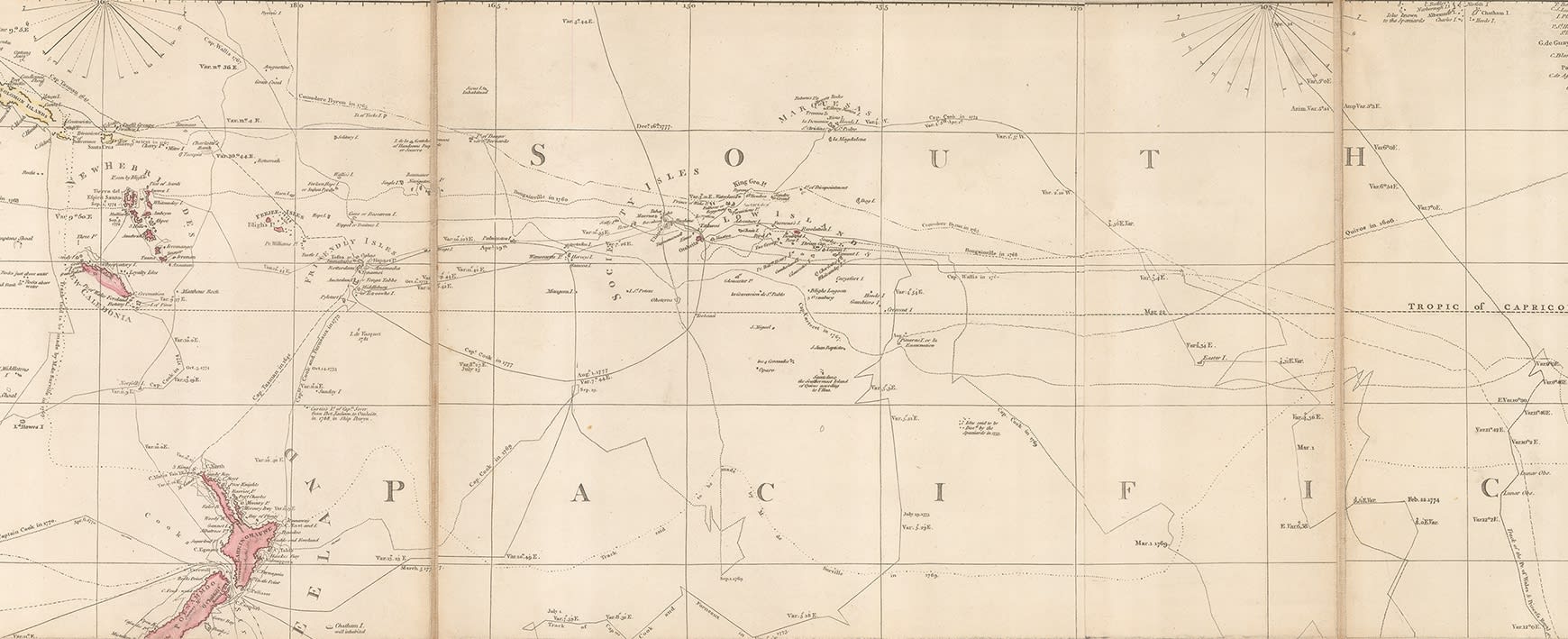

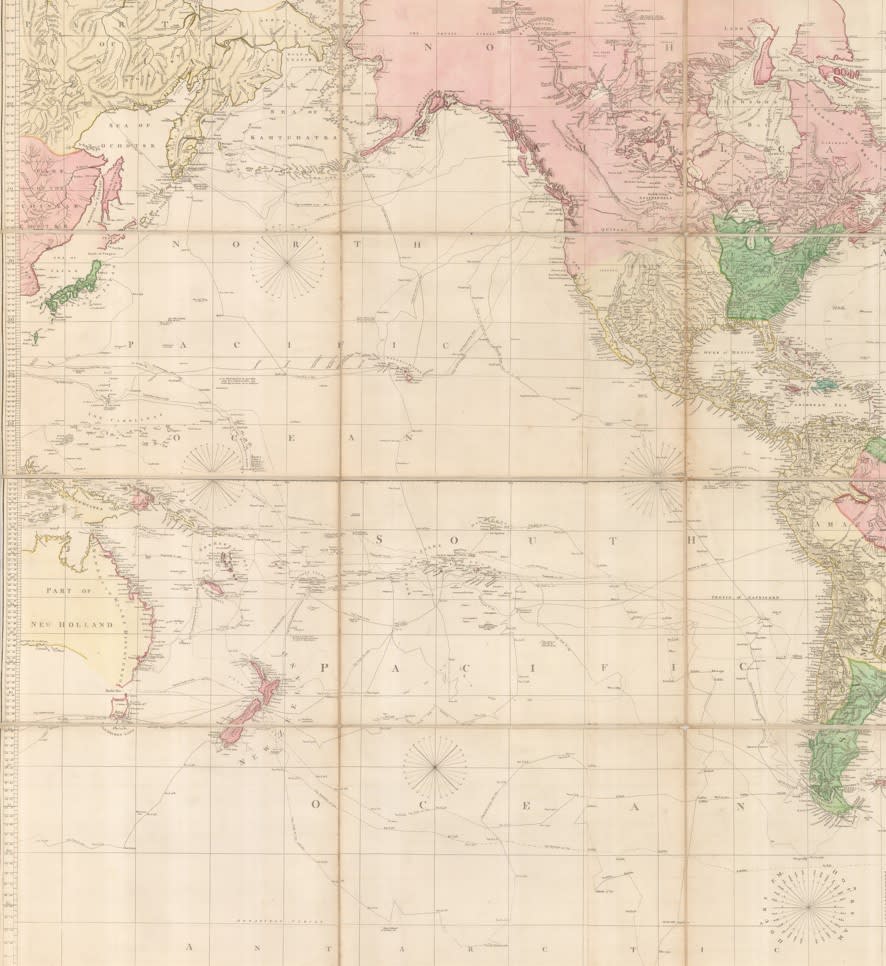

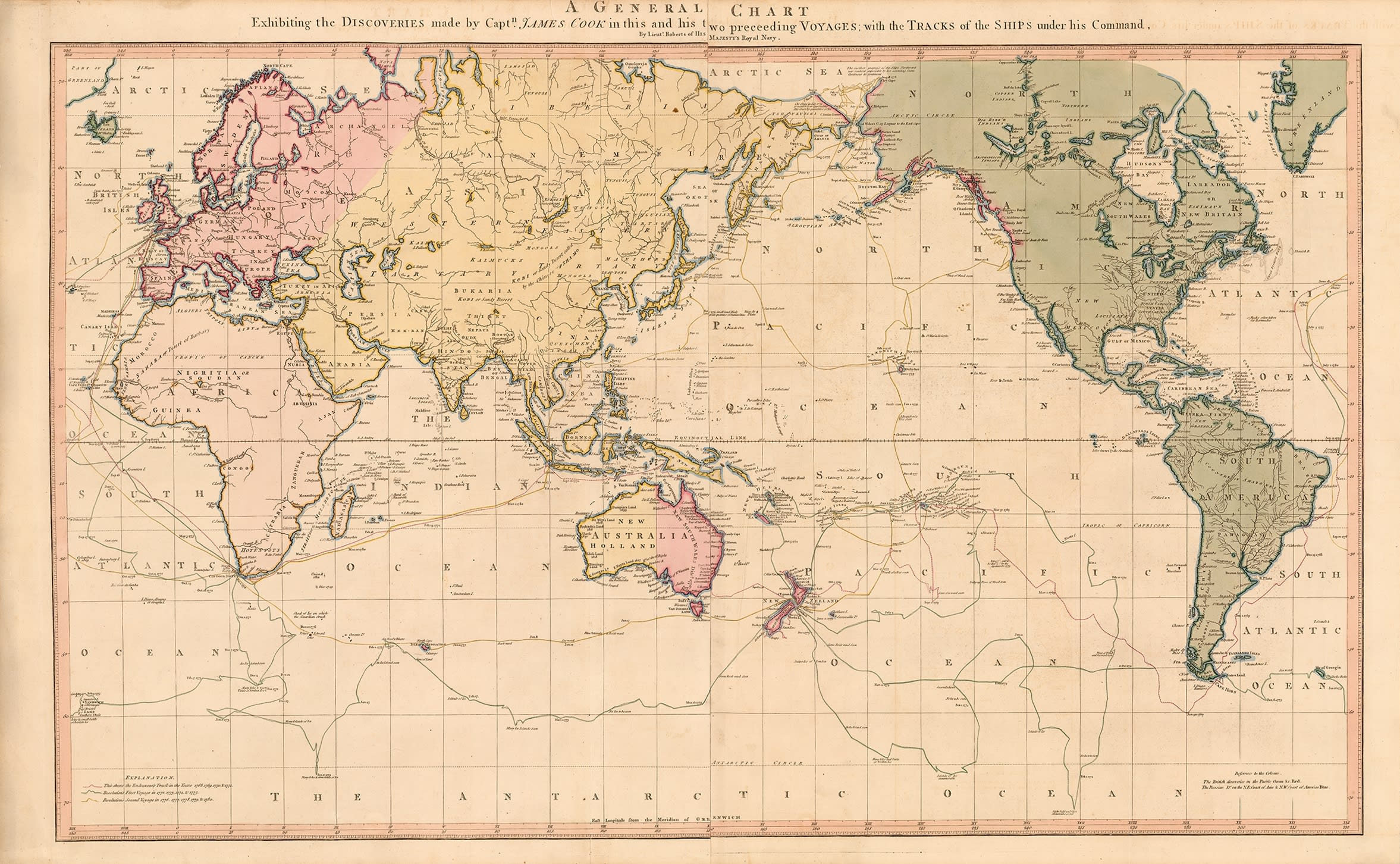

“A Chart of the World on Mercator’s Projection Exhibiting all the New Discoveries to the Present Time; with the Tracks of the most distinguished Navigators since the Year 1700 collected from the Charts, Maps, Voyages & c: and regulated from the Astronomical Observations made in three voyages: Performed under the Command of Captain James Cook in the Years……..” was Arrowsmith’s first map and set the exacting standard which established the reputation of the firm. It was linen backed, segmented and on two sheets. Its size immediately promoted it as a prestige piece and it must have been highly successful as it went through seven printings that have been traced between 1790 and 1808. Although, for the reasons mentioned above and due to the last reliable comparative survey being published in 1967, trying to trace the printings and the numbers of each is an inexact science. The printed date of 1790 on the map does not change, but the issue date can be traced both by the address of the imprint on the map, as the firm changed location several times during its existence and even more by the geographical detail.

In the title, one of the major points that Arrowsmith emphasizes are the marine voyages of exploration shown on the map. Captain James Cook, unsurprisingly, takes centre stage both on the map and in the title. Cook’s voyages, reports and tragic end made him both a hero and a celebrity to the public at the time. Popularity aside, his voyages also set a new standard for navigation and scientific accounts. It is often forgotten that the official reason for Cook’s first voyage was to record the transit of Venus over the Pacific. His search for New Holland or modern Australia was under sealed orders and not revealed even to him until he was at sea.

Less well known are the tracks of individuals such as Captain Phipps, later Lord Mulgrave, who in 1773 sailed as far as Spitzbergen or modern Svalbard in search of the Northwest Passage. The expedition is best known for the first detailed European description of a polar bear and for the inclusion of Midshipman Horatio Nelson in its crew.

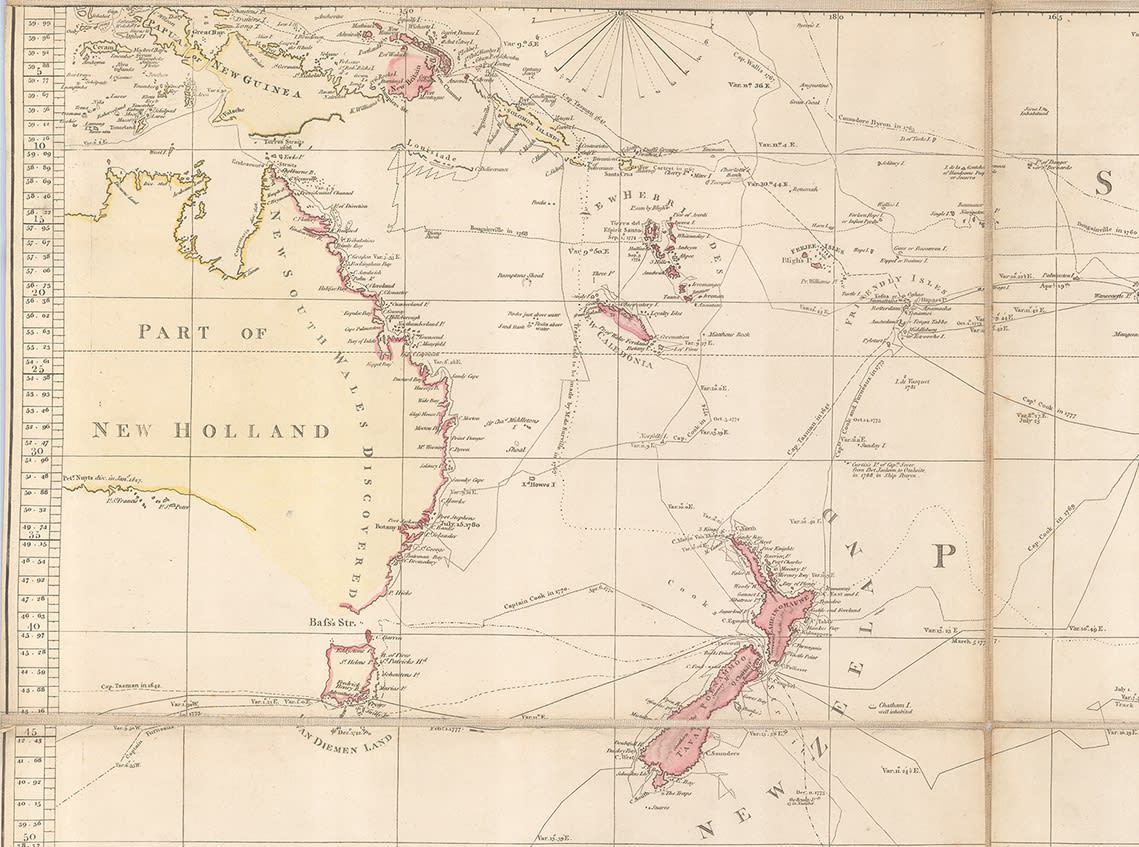

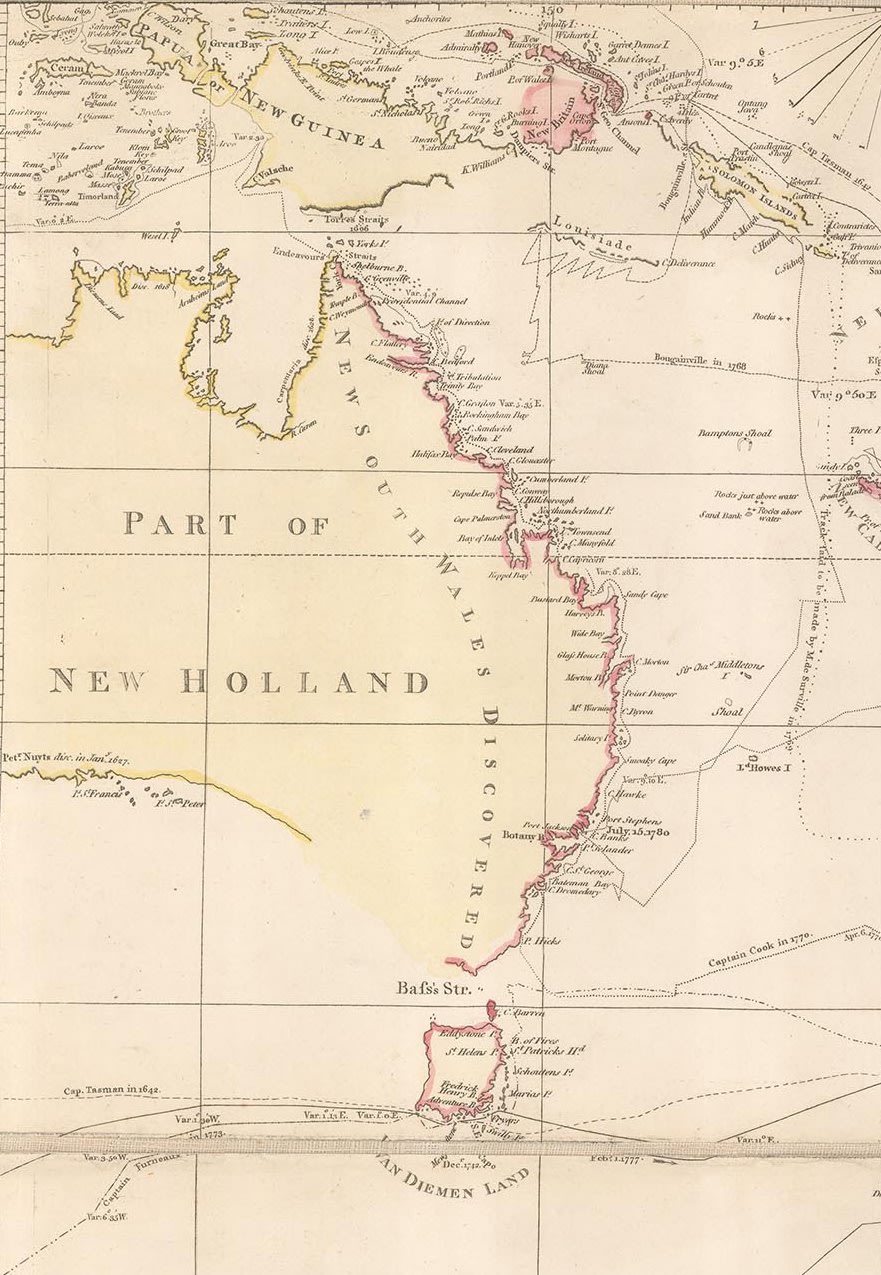

The Pacific shows several lesser known voyages of exploration such as the recent circumnavigation by Captain Philip Carteret in 1766-9; the track of Captain Tobias Furneaux, captain of H.M.S. Adventure who accompanied Cook on his second voyage but who was separated from the Resolution on two occasions and made several important Pacific discoveries, such as an early report on the southern coast of Tasmania. A curiosity is the early voyage of Pedro Fernandez de Queiros or Quiros, who in 1605-6 led a voyage in search of Terra Australis. It is believed he landed in modern Vanuatu, which he named “Australia del Espiritu Santo” or “Australia of the Holy Ghost” and Quiros himself was convinced that he had landed on the huge, uncharted southern continent often drawn amorphously on maps of the period to integrate multiple reports of land sighted in the far south by Spanish, French, Dutch and Portuguese mariners. Terra del Espiritu Santo continued to be a regular cartographic feature on early maps of Australia and the surrounding islands before Cook’s discoveries.

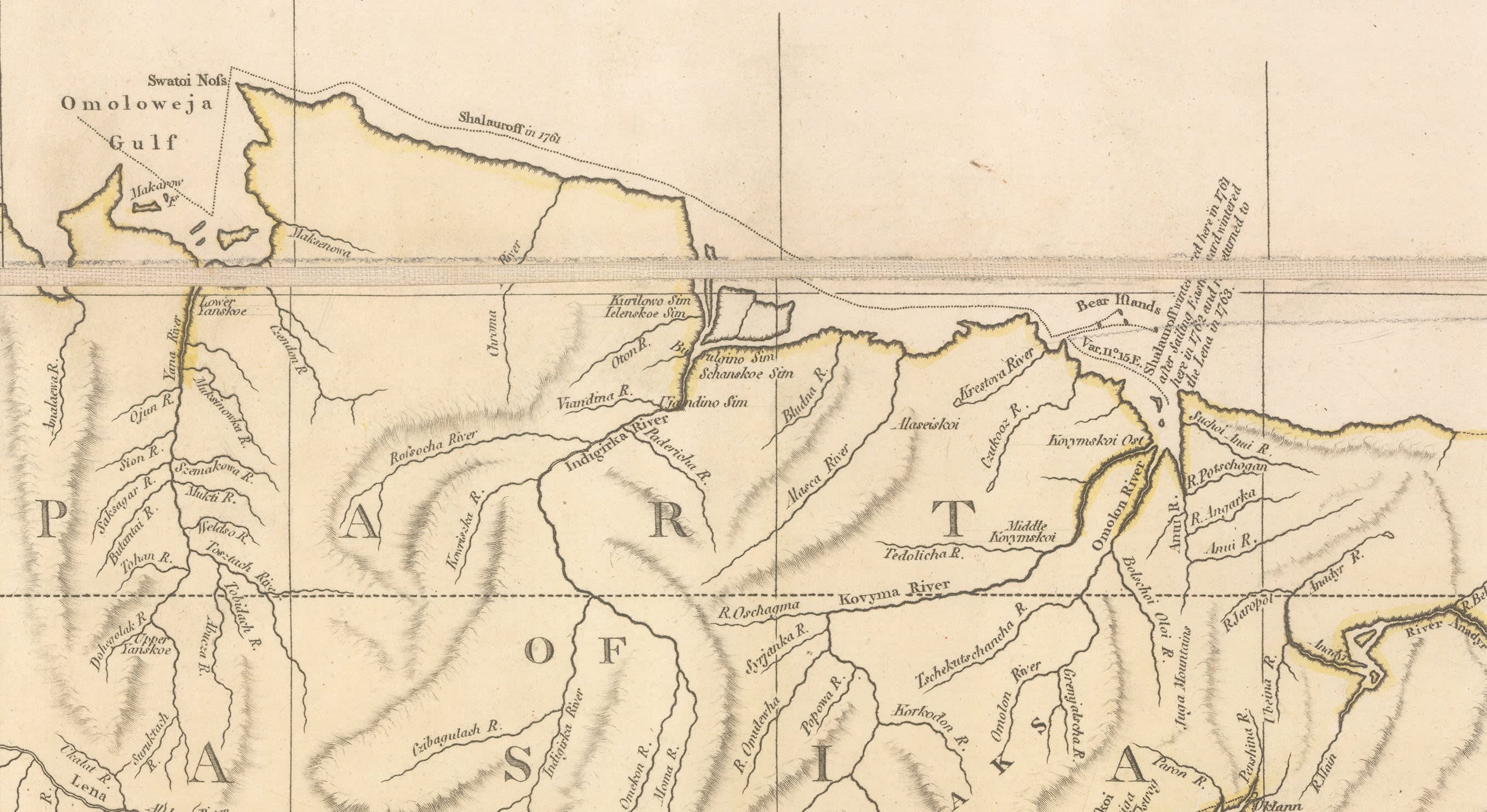

On the northeast coast of Asia, the map shows the obscure Polar expedition of the Russian explorer and merchant, Nikita Shalaurov, who was looking for the Northeast Passage. He failed in his attempt of 1761 so, unrecorded on this map, he tried again in 1764 and perished in the attempt.

Again, in the Pacific, a track shows another obscure journey, this time by a French merchant captain, Jean-Francois-Marie de Surville who undertook a voyage of Pacific exploration in 1769-70 on behalf of the French East India Company and arrived in New Zealand only a few days after Cook had left; sadly, he drowned off the coast of Peru in 1770.

This is just a small sample of the voyages marked but it does provide an indication of the truly comprehensive marine history present on this map.

____________

The terrestrial portions of this chart are subject to the same rigorous scholarship and precision as the oceans. Arrowsmith had access to many of the maps of important map makers of his generation both here and abroad. There are recognisable elements of the work of D’Anville, Bellin, Faden and Jefferys among many others. However, Arrowsmith is able to integrate their information with a clarity that was unmatched in its day.

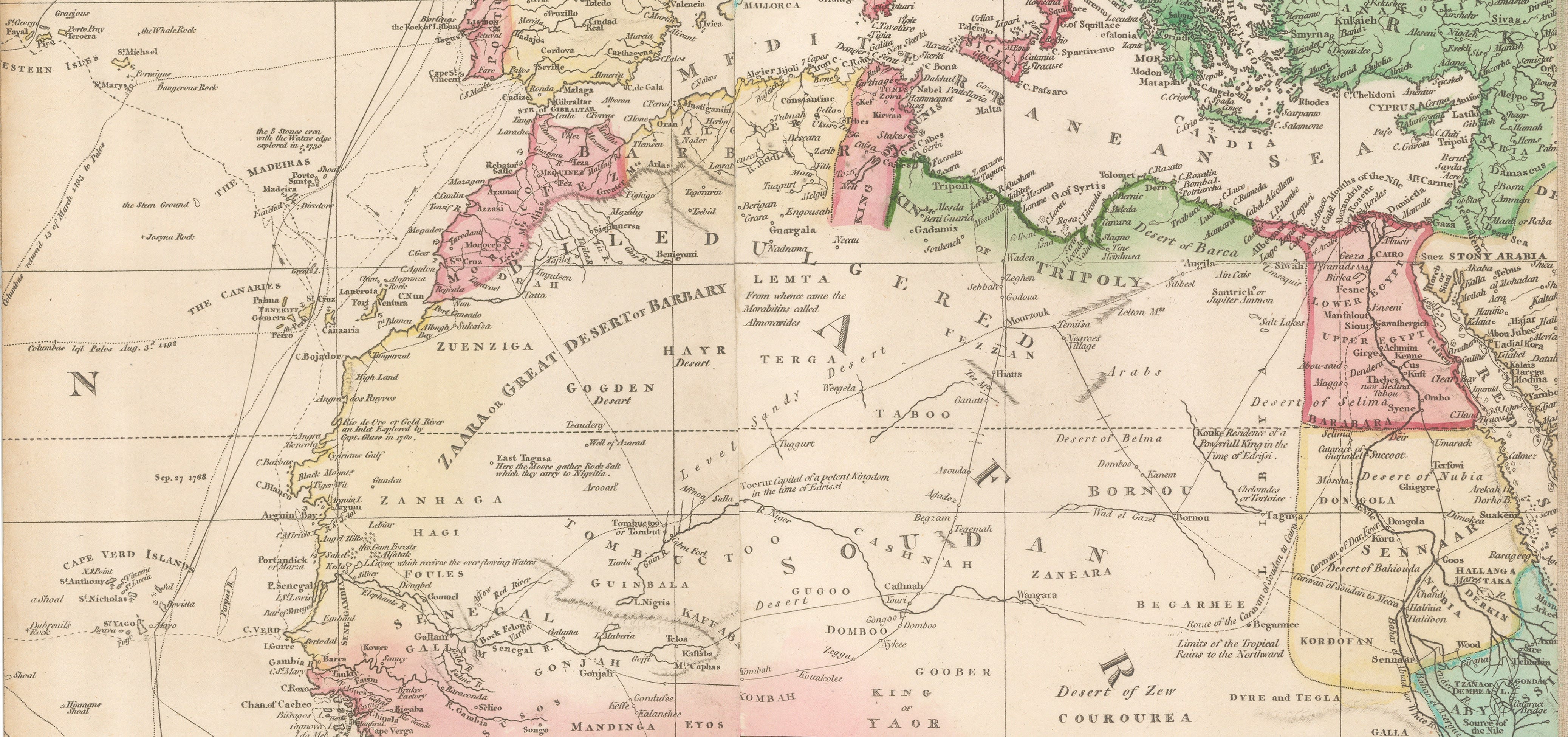

The North of Africa is a case in point; there was a sophisticated network of caravan routes across the Sahara desert which was centuries old, carrying trade goods from the continent, east to Arabia, Oman, the Levant, Persia and the Ottoman Empire. This map makes an early attempt to portray this network, including caravan routes going from “Soudan to Mecca”, “Soudan to Cairo” and further east, another caravan route is marked between Bahrain and Mecca.

Arrowsmith had contacts among early Africa explorers and indeed his wall map of Africa of 1802 is dedicated to the “ Members of the British Association for the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa”. Despite these contacts, much of the rest of African Continent is still unknown and Arrowsmith is rigorous in his maintenance of geographical integrity by leaving those areas blank.

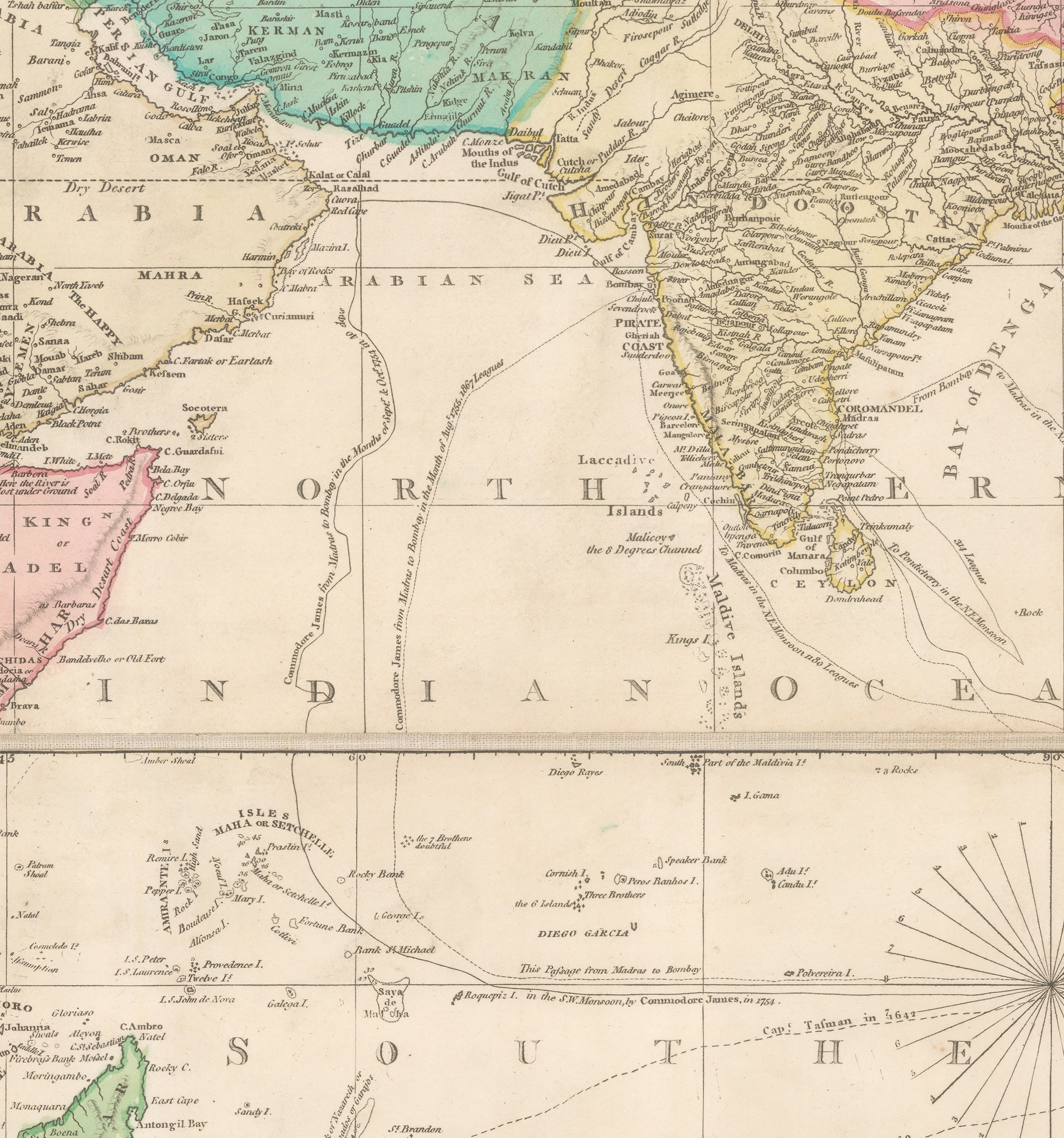

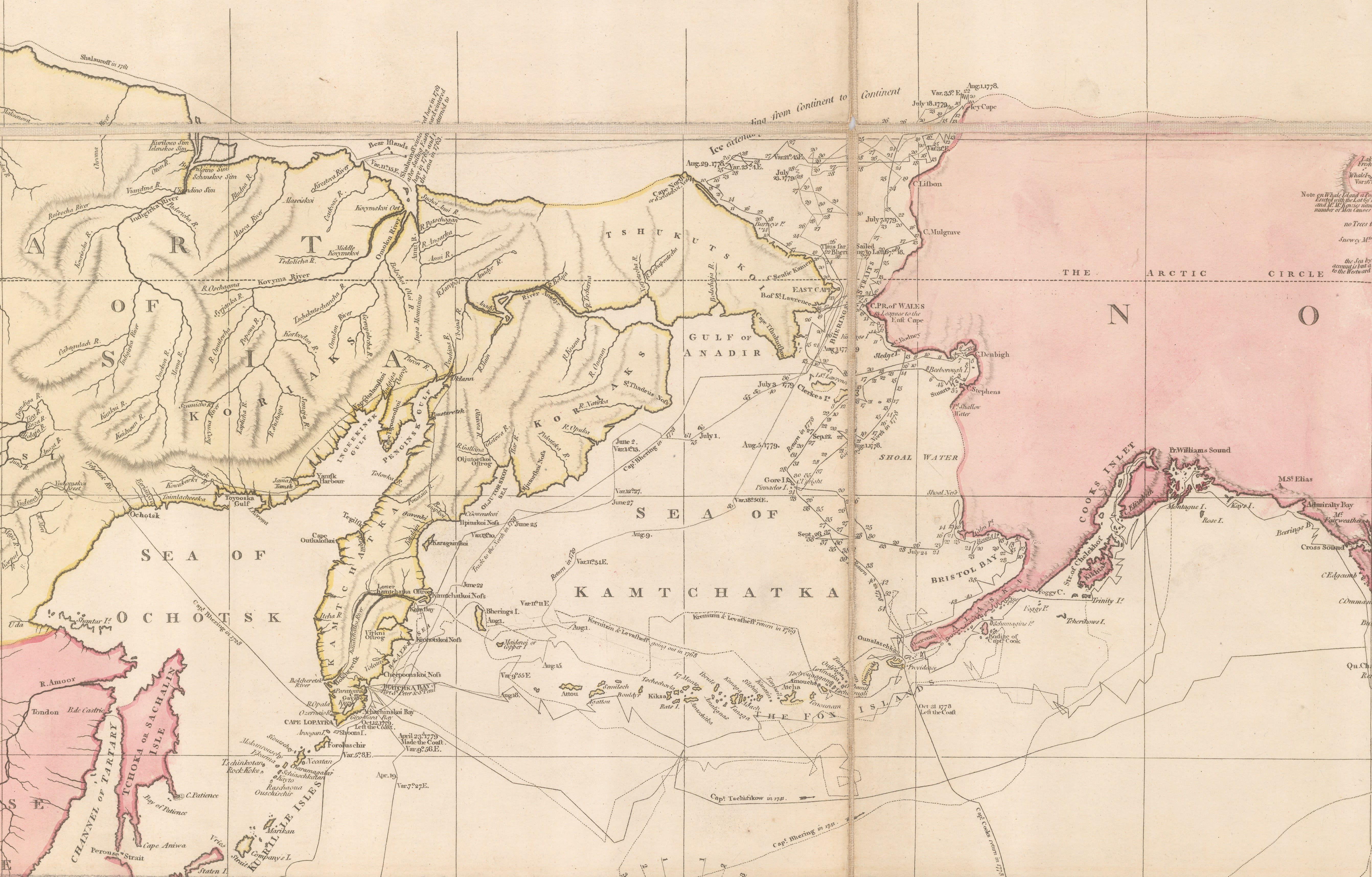

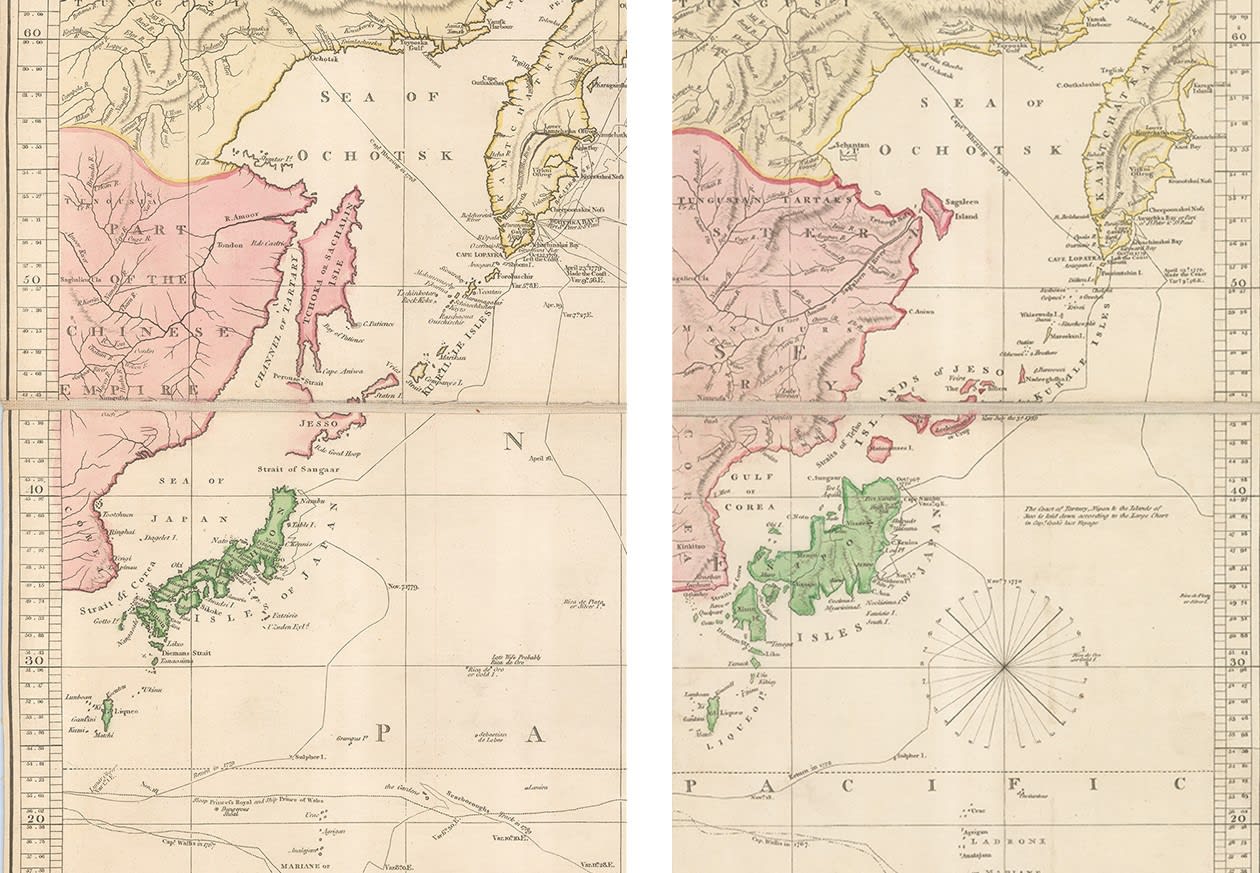

Asia again is sourced from multiple map makers, such as D’Anville for China, and van Keulen for the Dutch East Indies, explaining the lack of interior detail as the latter was mostly a chart maker. As marine commerce was the primary aspect of this region, that is where the emphasis on the map lies, with the Straits of Malacca, Singapore and Sunda together with the routes through them, clearly marked. Arrowsmith was able to rely on the maps of the British East India Company, especially those by James Rennell for his portrayal of the geography of the sub-continent. This was first-hand information and allowed Arrowsmith to draw a highly accurate rendition of the area. Further north, in Tartary, Arrowsmith uses the account of a truly extraordinary journey by Jean-Baptiste Barthelemy de Lesseps, who was one of three surviving members of the ill-fated circumnavigation of the Comté de La Perouse.

La Perouse set out from France on a scientific expedition on two ships, the ‘Boussole’ and the ‘Astrolabe’, in 1785. After reaching the Pacific and conducting many scientific experiments, he arrived at the Russian port of modern Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on the Kamchatka Peninsula in 1787. Lesseps had been educated in St. Petersburg and was brought onto the crew of the expedition for his knowledge of the Russian language. He disembarked with the expedition’s latest reports and set out on a journey from Kamchatka to Paris. It took him over a year but he survived and returned with his precious burden. Unfortunately, the rest of the expedition sailed south and shortly afterwards, all contact with it was lost. It was not until 1826 that a report was brought back of the wrecking and break-up of two large ships near the island of Santa Cruz in the Solomon Islands. This story as related by the natives was supported by the return of several objects and weapons which were traced back to the expedition.

Lesseps wrote an account of his own extraordinary journey which is clearly marked on Arrowsmith’s map. Lesseps himself lived an incident filled life as a member of the French diplomatic corps until 1834. Among other adventures, as Secretary of the French Legation to the Ottoman Empire, he was imprisoned in Constantinople in 1798 when Napoleon invaded Egypt and released only when the French army was evacuated in 1801. In 1812, he was appointed French Consul to Moscow, just a few weeks before Napoleon’s retreat. Incidentally he was uncle to Ferdinand de Lesseps, developer of the Suez Canal.

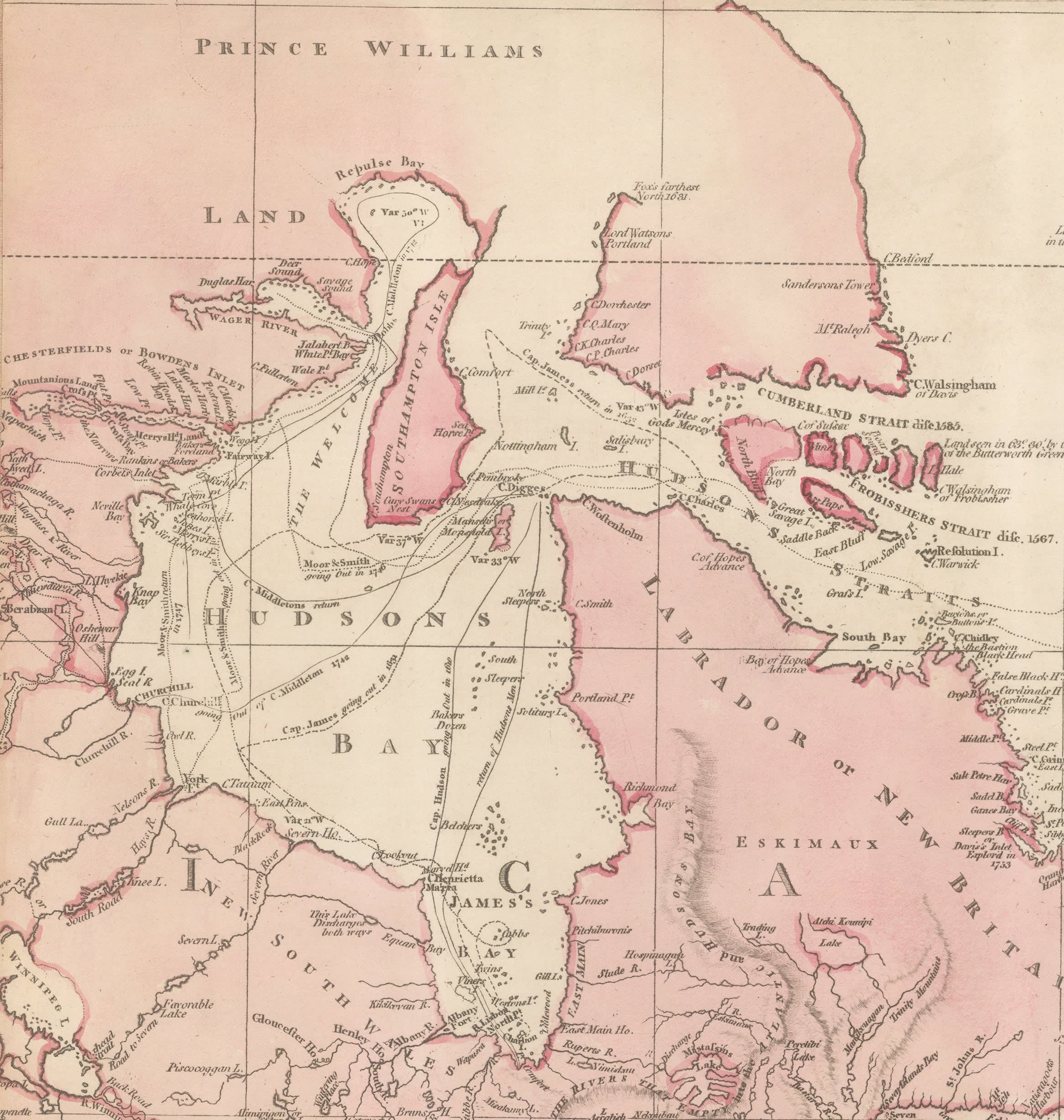

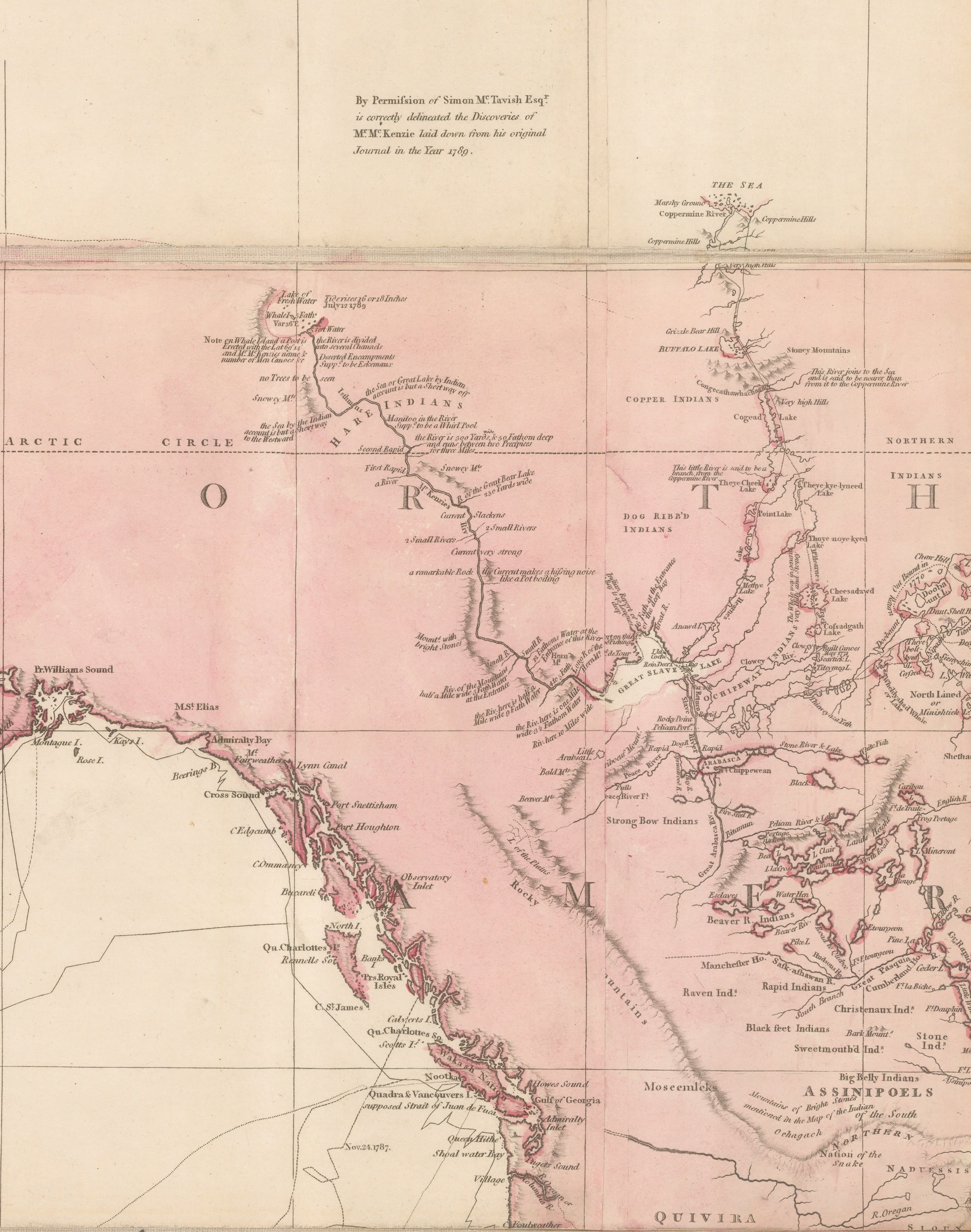

In North America, we have more examples of both Arrowsmith’s access and his tenacity in pursuing the most current of sources. A note on the upper part of Canada states that “by Permission of Simon McTavish Esq. is correctly delineated the discoveries of Mr. McKenzie laid down from his original journal in 1789.”

This note refers to Alexander Mackenzie’s exploration of northern Canada in what became known as the Mackenzie River Expedition of 1789 and in which Mackenzie followed a large river in the American Northwest, known to the local people as the Dehcho, hoping it would lead him to the Northwest Passage. It did not but it did lead him to the Arctic Ocean, emulating Samuel Hearne’s epic journey of 1772, along the Coppermine River. Simon McTavish was one of the founding members of the Northwest Company under whose auspices Mackenzie conducted this expedition. Somehow, Arrowsmith convinced McTavish to let him both examine and publish the route from Mackenzie’s diary on his map before the official publication of the report in 1801.

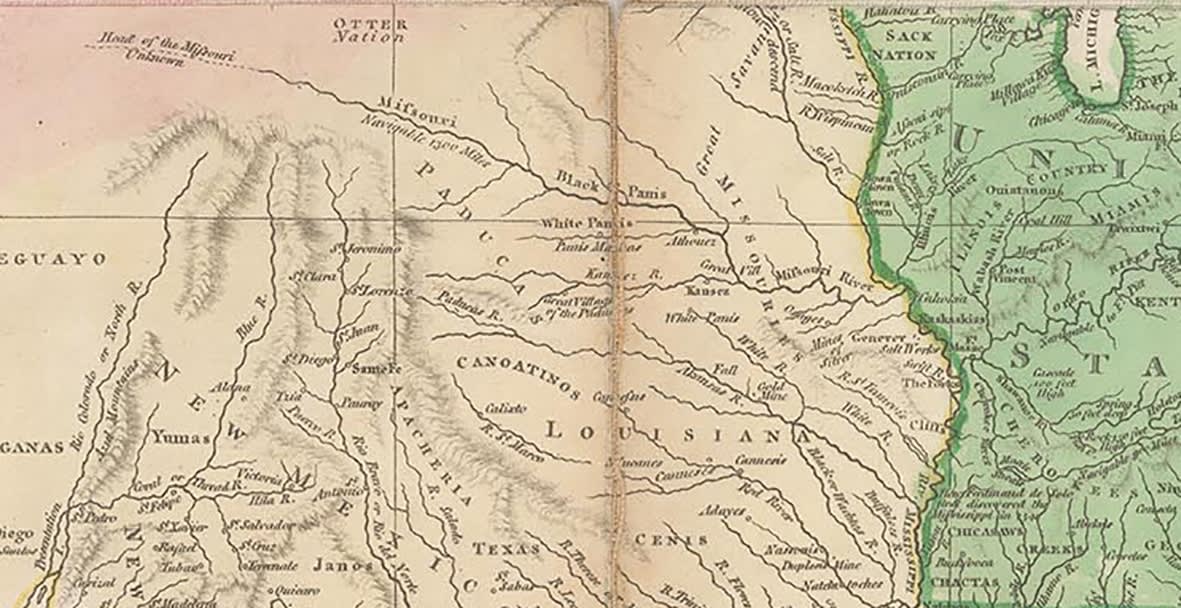

Arrowsmith must have also had extraordinary contacts within the Hudson’s Bay Company as he integrated the information collected by another important surveyor of the interior of Canada, Peter Fidler. This information was compiled in the early 1790s so it only begins to appear in the later versions of this Chart, as well as Arrowsmith’s map of North America in 1802. This is yet another example of Arrowsmith’s ability to keep abreast of events in the world of exploration. Fidler’s reports also included the latest information on the region of the Upper Missouri River. It was for this reason that Arrowsmith’s map of North America was used by Lewis and Clark’s Expedition into the American West in 1805-6.

As well as showing multiple voyages, discoveries and historical events there is one last extraordinary aspect of this map which we have been unable to explain; its depiction of the eastern coast of Asia, Japan and Australia.

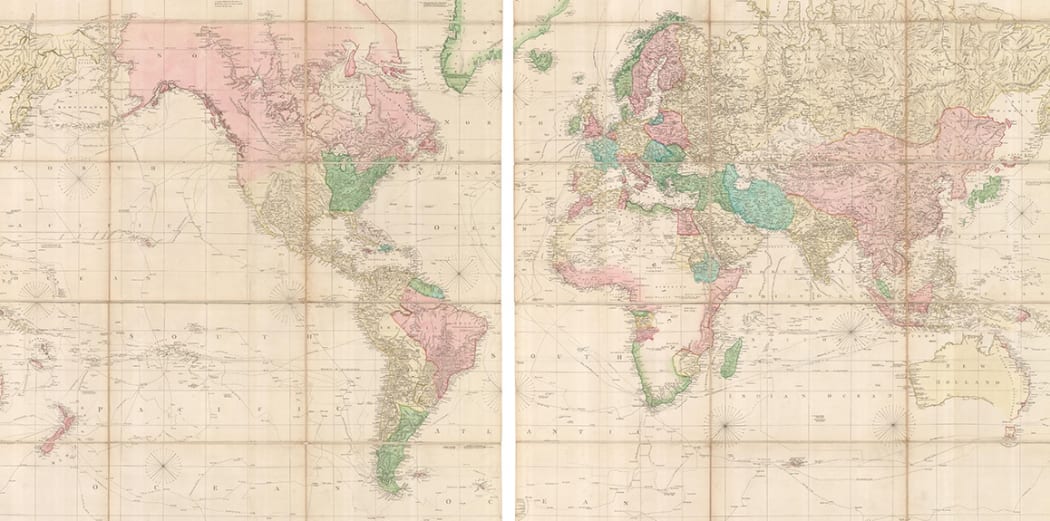

Due to Arrowsmith’s scaling of the Mercator Projection, he overlaps his map in the extreme left and extreme right showing the eastern part of Australia, the east coast of Asia and Japan and its islands on both sides. Yet the geographical versions of these areas differ markedly from one side to the other.

Arguably the most obvious difference is the shape of Japan; the left side follows a model first drawn by Jean D’Anville in his famous atlas for Du Halde’s “Description de L’Empire de la Chine and de la Tartarie Chinoise” of 1737; the right side shows Japan as depicted by Engelbert Kaempfer in 1727.

Additionally, although the difference between Japan is the most startling, there are other major differences between the two sides, such as the depiction of Sakhalin Island, New Guinea and detail on the east coast of Australia.

We have been unable to find a valid reason for this discrepancy. There is a small note on the right side which states that “the coast of Nipon, Tartary and the islands of Jeso is laid down according to the large chart of Capt. Cook’s last voyage.” Certainly, while Cook sailed in that region, it was not the main focus of his explorations and his sighting of the Japanese coast was only brief; he certainly did not approach the eastern coast of Asia for any great length. Examination of the chart by Henry Roberts, which was the chart of the world from Cook’s published report, bears little resemblance to that section of Arrowsmith’s map.

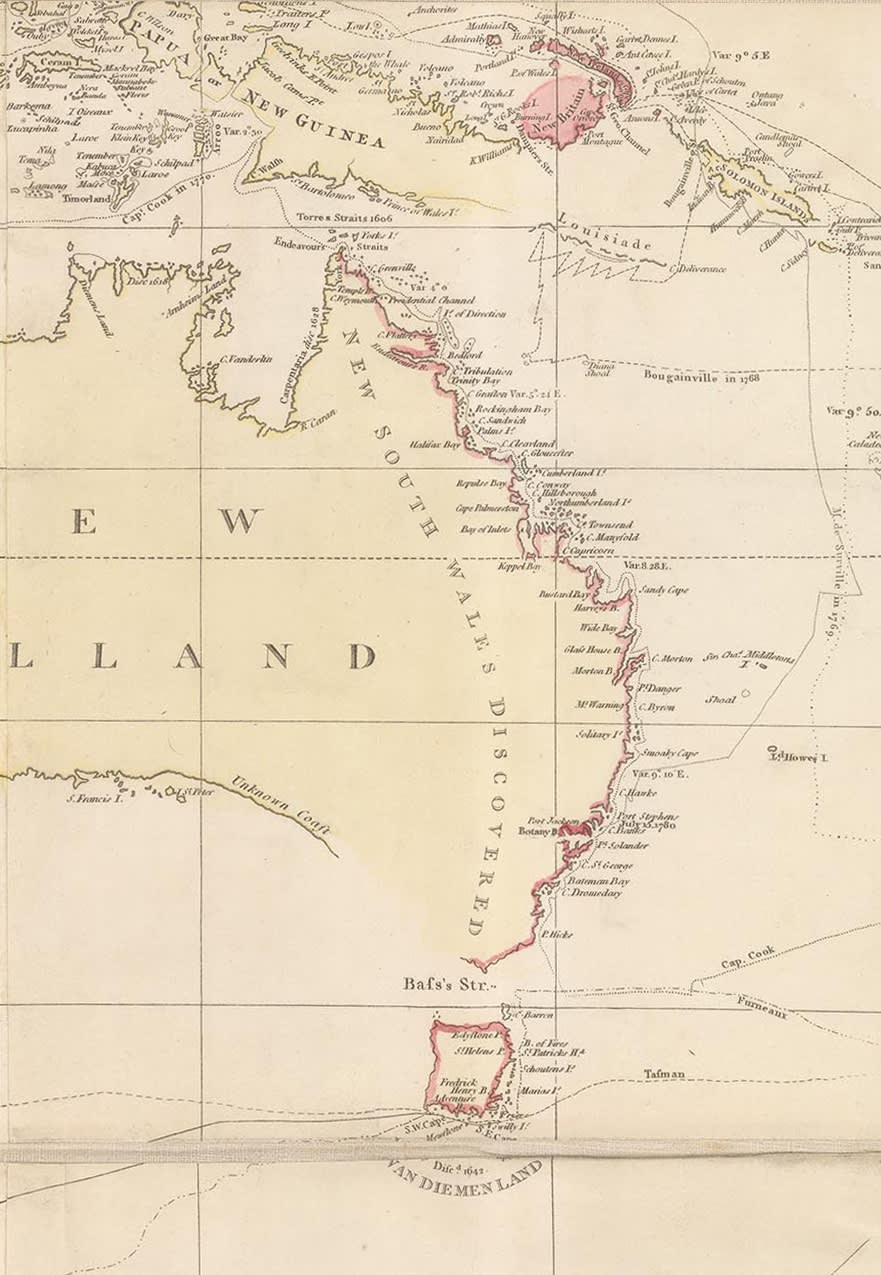

Roberts (Henry): “A General Chart Exhibiting the Discoveries made by Captn. James Cook” Published circa 1784, London [WLD3806]

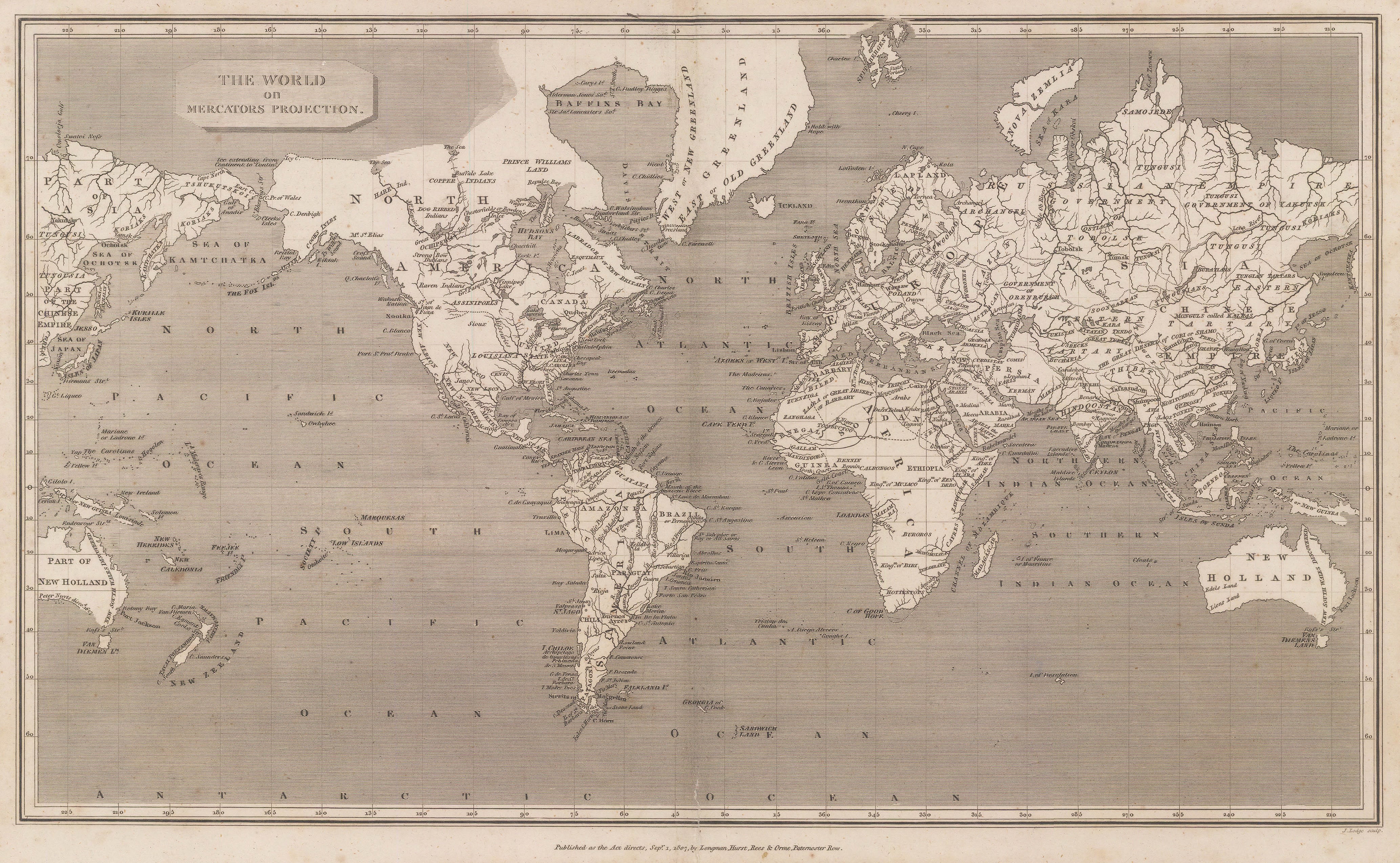

To add to the mystery, Arrowsmith persists with this anomaly on his other maps, including those present in this atlases. Below is an illustration of a world map from his “A New Atlas of Ancient and Modern Geography” which clearly shows these geographical details, with an overlapping world and distinct differences between the portrayals of Australia and Japan.

Arrowsmith (Aaron): “The World on Mercator’s Projection” Published 1807, London [WLD4404]

Arrowsmith is the only map maker we have recorded portraying this possibly unique anomaly.

As stated in the beginning of this article, it is very difficult to date the individual maps but by studying both the bibliographies and the geography of this map, we believe that the date of this particular example is circa 1802. It does however show both the Bass Strait, separating Australia and Tasmania, discovered in 1798-99 and the route, and discoveries of Vancouver’s expedition of 1791-5, the first issue of this map to do so.

It is difficult to imagine just how much of an impression or effect this map had on the public when it was first issued but certainly judging by its long publishing history, the longevity of the firm as a commercial business and Arrowsmith’s reputation during his life suggests that it made an immediate and lasting impact. That reputation as a cartographer and scholar has increased after his death and this map is now considered a geographical paradigm.